The Quack Doctor is currently providing Victorian remedies for Sky Living’s online newspaper, The Inquisitor, which accompanies the channel’s new ten-part drama, Dracula. If you are visiting the site for the first time via sky.com, welcome!

‘For the blood is the life’: the evocative quotation appears in the very first scene of Sky Living/NBC’s Dracula as a mysterious figure gives our anti-hero’s corpse the sustenance it needs to rise from the grave.

‘For the blood is the life’: the evocative quotation appears in the very first scene of Sky Living/NBC’s Dracula as a mysterious figure gives our anti-hero’s corpse the sustenance it needs to rise from the grave.

The identity of Dracula’s resurrectionist – which is revealed within the first episode – is rather unexpected for those familiar with Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel. His words, however, famously appear in the book, and Victorian readers would have recognised them as the advertising slogan of one of the era’s best-known patent medicines.

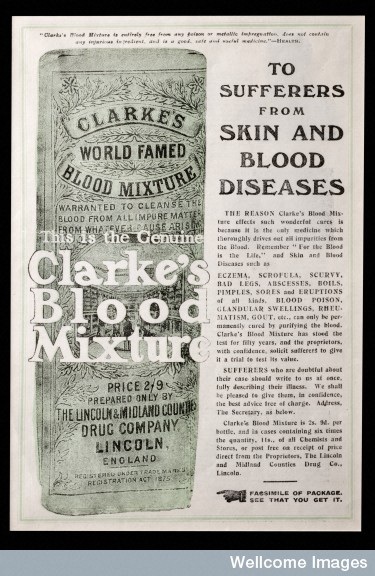

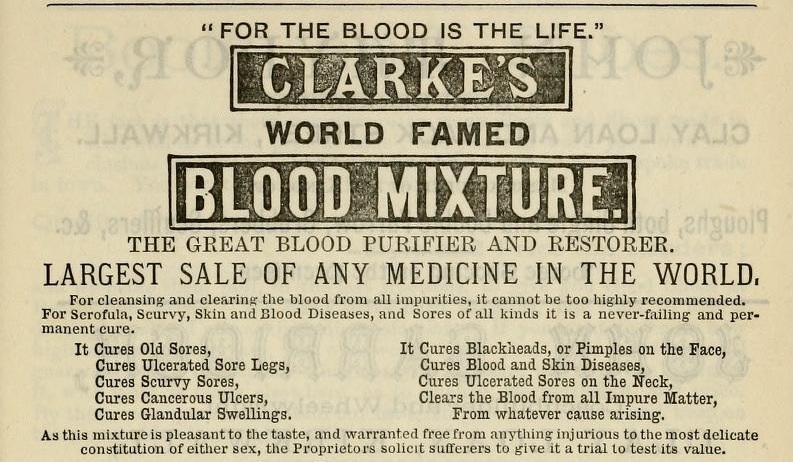

‘For the blood is the life’ (originally from Deuteronomy 12:23’s instruction not to consume blood – so go easy on the black pudding if you don’t want to be smited) was used to promote Clarke’s Blood Mixture, a tonic invented in the 1860s by Lincoln chemist Francis Jonathan Clarke. He was only 19 years old when he opened his first shop and put the Mixture on the market, and his commitment to massive advertising expenditure soon secured the product’s fame.

The Mixture did not claim to cure all diseases – only those caused by ‘bad blood’. Fortunately for Clarke’s business, that encompassed pretty much everything from blackheads to cancer.

Clarke was a popular chap, serving as mayor of Lincoln four times and becoming known for his generosity to the poor, but his good humour was allegedly less altruistic at times. In 1895, a publication called Exposures of Quackery claimed that, many years earlier, he had faked a glowing endorsement from chemical analyst Dr Alfred Swaine Taylor. When teased by a friend about it, he had apparently laughed and said of Taylor, ‘I shall wait a few years till that old fogey is dead, and then no one can prove that he did not give me a testimonial.’

The authors of Exposures also expressed concern about the Mixture’s main ingredient, potassium iodide, suggesting that it was present in sufficient quantities to cause skin eruptions. In the early 20th century, dermatologist George Pernet of the West London Hospital implicated the Mixture in the case of a 50-year-old man whose skin broke out in ‘raised, purulent, and crusted,’ blisters the size of a florin.

By the time Exposures came out, Clarke was not around to defend himself, having died in 1888 at the age of just 46. The Mixture, however, continued to thrive under the business he’d set up, the Lincoln and Midland Counties Drug Company. With various changes to its formula – including the addition of sarsaparilla – it remained on the market until the 1960s.

Its fleeting role in Stoker’s Dracula arrives in chapter 18, when asylum inmate R M Renfield explains his obsession with eating living things in order to acquire their life-force.

‘The doctor here will bear me out that on one occasion I tried to kill him for the purpose of strengthening my vital powers by the assimilation with my own body of his life through the medium of his blood, relying of course, upon the Scriptural phrase, “For the blood is the life.” Though, indeed, the vendor of a certain nostrum has vulgarised the truism to the very point of contempt. Isn’t that true, doctor?’

Although he doesn’t mention Clarke’s by name, the product was advertised so heavily that many readers would immediately get the reference.

Among the Blood Mixture’s targets was syphilis, a disease to which some biographers have attributed Bram Stoker’s death in 1912. The first effective antisyphilitic treatment, Salvarsan, was available by then, but at the time of Dracula’s publication, those suffering from the euphemistically described ‘impurities of the blood’ were still relying on dangerous treatments involving mercury. Tonics like Clarke’s were gentler and easier to keep secret, but they did not cure the disease either. If you were suffering from tertiary syphilis, no amount of Clarke’s Blood Mixture would stop your impurities from sucking away your life-force.

Sources:

By the Editor of Health News, Exposures of Quackery: Being a series of articles upon, and analyses of, various patent medicines, 2nd ed. vol 1 (London, The Savoy Press) 1897.

Homan, Peter; Hudson, Briony; Rowe, Raymond C., Popular Medicines: An Illustrated History, (London, Pharmaceutical Press), 2007.

Pernet, George, M.D. ‘ Case of Severe Iodide Eruption’, Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 10 (Dermatological Section), 1917, 17–18.

Stoker, Bram, Dracula, 1897. The first US edition is available to read online at the Internet Archive.

Hi I remember buying and drinking this in the 1960s.I had very bad acne it worked for a while.I can still remember the smell.an elderly lady told me about it.

Where can I get it?