No one likes to be the hapless person who wanders into the garage and finds a forgotten turkey carcase humming with maggots and surrounded in a fug of pungent effluvia. I suppose it would be a great story if this had been a defining moment of my teenage years, inspiring me to embark on a glittering international career in forensic entomology, but in reality I just helped (i.e. watched) my mum transfer it to the bin and went about my day. Little did I know that, according to one early twentieth-century farmer, I was breathing in a cure for tuberculosis …

From the human perspective, maggots are repulsive. They do, however, have their uses – and not just to clear dead things from the environment. Their employment in both ancient and modern medicine to debride necrotic wound tissue is well known; this article concerns a different episode in their medical story. It took place in the pre-antibiotic days of 1911, and could hold the potential for development in a post-antibiotic future too.

The birth of the Maggotorium

In August 1911, a chemist reported to the Chemist and Druggist about a visit to an unusual treatment centre. The place was Jerusalem Farm, Thornton, near Bradford, where Arthur Edward Bryant grew maggots for fishing bait. Bryant, who had suffered pulmonary tuberculosis, claimed that since he started his enterprise he had entirely recovered. He now invited other TB patients to inhale the gases in his maggot sheds – with apparently excellent results.

Arthur Bryant was born in Preston Bissett, Buckinghamshire, in 1879. He left home at seventeen, keen to escape a demoralising life of working 100 hours a week only to have to give all his wages (except one penny) to his mother. He set off for Yorkshire and took various jobs as a brickworker, farmhand and collier, saving £6 in the Yorkshire Penny Bank within his first year. Bryant was also a keen angler, and began breeding maggots on a small scale to use and sell. By becoming a knackerman too, he always had enough decaying flesh to keep his wriggly crop happy, and soon became known as ‘The Maggot King’.

In 1911, the business was thriving, and with Bryant’s tuberculosis symptoms gone, he opened up his maggot-breeding sheds to people who had lost hope with the conventional sanatoria of the time. The ‘Maggotorium’ was born.

‘One gets used to it’

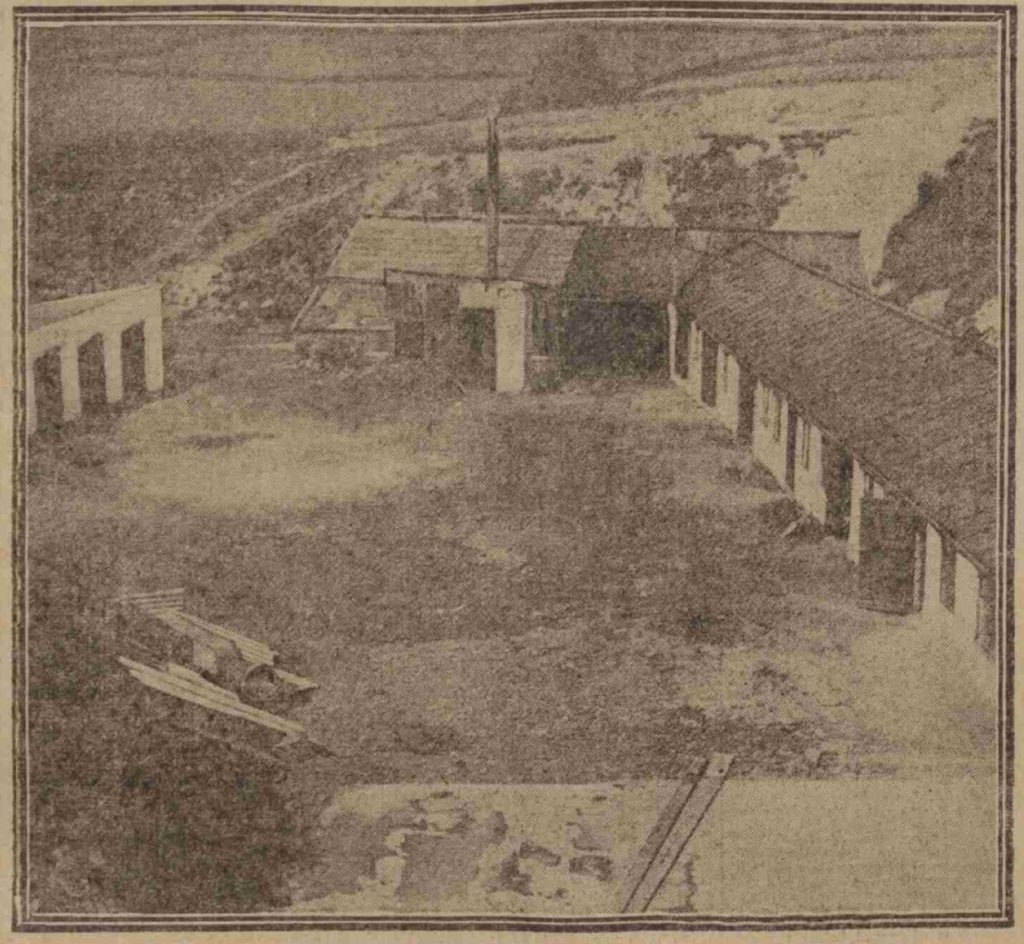

The Chemist and Druggist‘s correspondent described an unenticing scene. The patients spent three hours in the morning and two hours in the afternoon inhaling the stench of decaying meat, which hung on hooks around the room. Once the meat was sufficiently far gone, it got transferred to galvanised tanks, heated by hot-water pipes, where blowflies ‘hurr[ied] on the decaying stage’ and deposited their eggs.

‘On first entering one is overcome with the heat and the strong smell of ammonia, but after a time one gets used to it,’ the correspondent said.

Another contemporary description agreed that the place did not offer the height of luxury:

‘He has two long, narrow sheds, divided into compartments, separated from each other and each entered by a separate door; each shed is traversed by pipes for heating purposes. On either side of the door are troughs, in which are placed fragments of the carcases (offal, and so forth) of the beasts dealt with. While lying here flies have free access for the deposition of eggs, which rapidly develop into larva at suitable temperatures.’ (Yorkshire Evening Post, 9 Sept 1911.)

Bryant himself, the Post said, was ‘a man of healthy appearance, free from all signs of sickness, and of an exceptionally happy and light-hearted disposition.’ His organisational skills appeared lacking – he kept few patient records and was uncertain how many people had undergone treatment or benefited from it – but he came across as ‘a man of active and good intelligence and transparent honesty.’

Not merely antiseptics but germicides

Persuaded by his own experience that the treatment worked, Bryant nevertheless sought to confirm its efficacy scientifically, and called in the Bradford City Analyst, Mr F. W. Richardson, to carry out some tests of the maggoty air.

Richardson found ammonia and trimethylamine present in significant quantities, as well as mono- and dimethylamine and traces of indole and skatole (components of poo smell). On experimenting further he found that even weak solutions of these substances destroyed microbes after a few hours’ exposure:

‘We are therefore of the opinion that they are not merely antiseptics but germicides. Thus do we confirm the opinion which I expressed, as to the action of maggotorial fumes. These fumes, evidently when inhaled, come in contact with the tubercle bacilli, and reduce their vitality, or may even kill them, while, according to your [i.e. Bryant’s] investigations, these fumes do not injuriously effect the human organism.’

Bryant did not charge patients to attend the maggotorium; on the contrary, he provided them with food at his own expense. The ‘Maggot Cure’ wasn’t a money-making scheme but one whose discoverer went out of pocket in his enthusiasm to make it available to all. He put together plans for a more comfortable sanatorium room above the maggot sheds, where patients could benefit from the fumes without having to sit next to decaying flesh. Although these were initially rejected, Denholme Urban Council passed Bryant’s revised plans in October 1911.

For reasons that are unclear, the scheme did not come to fruition, and by 1915, Bryant had returned to Preston Bissett, where he continued to farm maggots for angling alongside a diverse range of other crops – but didn’t pursue the sanatorium idea. Although there was medical interest in the treatment of TB through inhalation, Britain had quite a lot on its plate at this period and the maggot gases’ potential appears to have been neglected, other than by a few copycat maggotoria.

King of the Maggots

The rest of Bryant’s life was by no means uneventful, however. His fame in the angling world meant that by the 1930s he could enjoy the fact that a letter addressed to ‘The Maggot King, England’ could reach him from anywhere. In 1936, he won the All-England Angling Championship with a record catch of 35lb 1oz of bream.

Bryant became a leading figure in local government politics as an outspoken, honest campaigner for the public good. This led to many a clash with his fellow councillors but as one colleague put it ‘there is something about Arthur Bryant and you cannot help liking him.’

Bryant inaugurated the St Dunstan’s Cup, encouraging Bucks villages to compete to raise the most money for the St Dunstan’s charity (now Blind Veterans UK), and he used the wealth accumulated from bait sales to try to make a difference to people’s lives. In 1942, for example, he offered to donate eight houses to Bucks County Council in order to provide rent-free accommodation for people struggling to subsist (the council refused) and he was renowned for never claiming any expenses for local government work. So perhaps it is possible for politicians, like maggots, to have their positive side.

The maggots of the future?

In 2007, Milton Wainwright, Amar Laswd and Sulaiman Alharbi of the University of Sheffield showed that gases produced by blue blowfly larvae on beef heart inhibited the growth of Mycobacterium phlei (which served as a model for the more dangerous Mycobacterium tuberculosis). A simulated version of the maggot gas, comprising di- and trimethylamine and ammonia, had a similar effect, as did ammonia vapour alone. Wainwright et al. did not rule out the possibility that Bryant’s Maggotorium had successfully treated TB patients – and, given the increasing resistance of the TB bacillus to antibiotic drugs, they suggested that ‘perhaps we may not have seen the last of maggot inhalation therapy.’

It’s unlikely that future patients would have to sit in a shed next to a trough of rotten horse meat, but if research does end up producing an effective TB treatment based on the gaseous emissions of maggots, we could one day benefit from the legacy of The Maggot King.

Sources:

‘Is there anything in it?’, Yorkshire Evening Post, 12 July 1911

‘A novel proposal of the Bradford Maggotorium’, Yorkshire Evening Post, 22 July 1911

‘The Maggot Cure for Consumption’, Chemist and Druggist, 5 August 1911

‘Bradford Maggotorium’, Yorkshire Evening Post, 9 September 1911

‘Maggot Factory: Plans for Sanatorium at Denholme’, Leeds Mercury, 4 October 1911

‘Mr Bryant tells his story’, Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press, 17 October 1936

‘Norton’s Place Houses’, Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press, 19 December 1942

‘Passing of County Councillor A. E. Bryant’, Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press, 21 December 1946

Wainwright, M., Laswd, A., and Alharbi, S., ‘When maggot fumes cured tuberculosis’, Microbiologist, March 2007, pp. 33-35.

Lucky Bradford – we actually had another famous maggot farm, and during the First World War the remaining one aided the war effort by offering recruits the opportunity to march through the maggot farm to allay any fears of potential tb cases occurring while fighting for King and Country.

The farm still existed when in the late 60s/early 70s. I worked not far away. If the wind was in the wrong direction the stench was terrible, and if I had to send staff out to work in the same village they were very reluctant to do so. I think it was closed down in the 70s, probably by the Environmental Health Dept!

Dr. Christine Alvin

That’s interesting to know – thank you!