Suzie Grogan, author of Shell Shocked Britain: The First World War’s Legacy for Britain’s Mental Health

Suzie Grogan, author of Shell Shocked Britain: The First World War’s Legacy for Britain’s Mental Health explores the commercial remedies that claimed to tackle the psychological effects of war.

In the pre-welfare state world we can barely imagine, it was natural for those suffering a myriad different ailments to first consult their pharmacist for a ‘cure’. Many of the adverts that filled the pages of the national and local papers and weekly magazines seem amusing to us now, claiming as they do to help everything from lung disease to liverishness, heart disease to haemorrhoids. The People’s Friend for example, ran adverts such as ‘Don’t gas, take Beecham’s Pills’, ‘At Home and Abroad insist on Milkmaid Cocoa’ and ‘Daisy, cures headache and neuralgia’. The last of these is headlined ‘I wonder if he’s safe…’ and offers Daisy as a cure for ‘war headaches’.

For Shell Shocked Britain: The First World War’s Legacy for Britain’s Mental Health

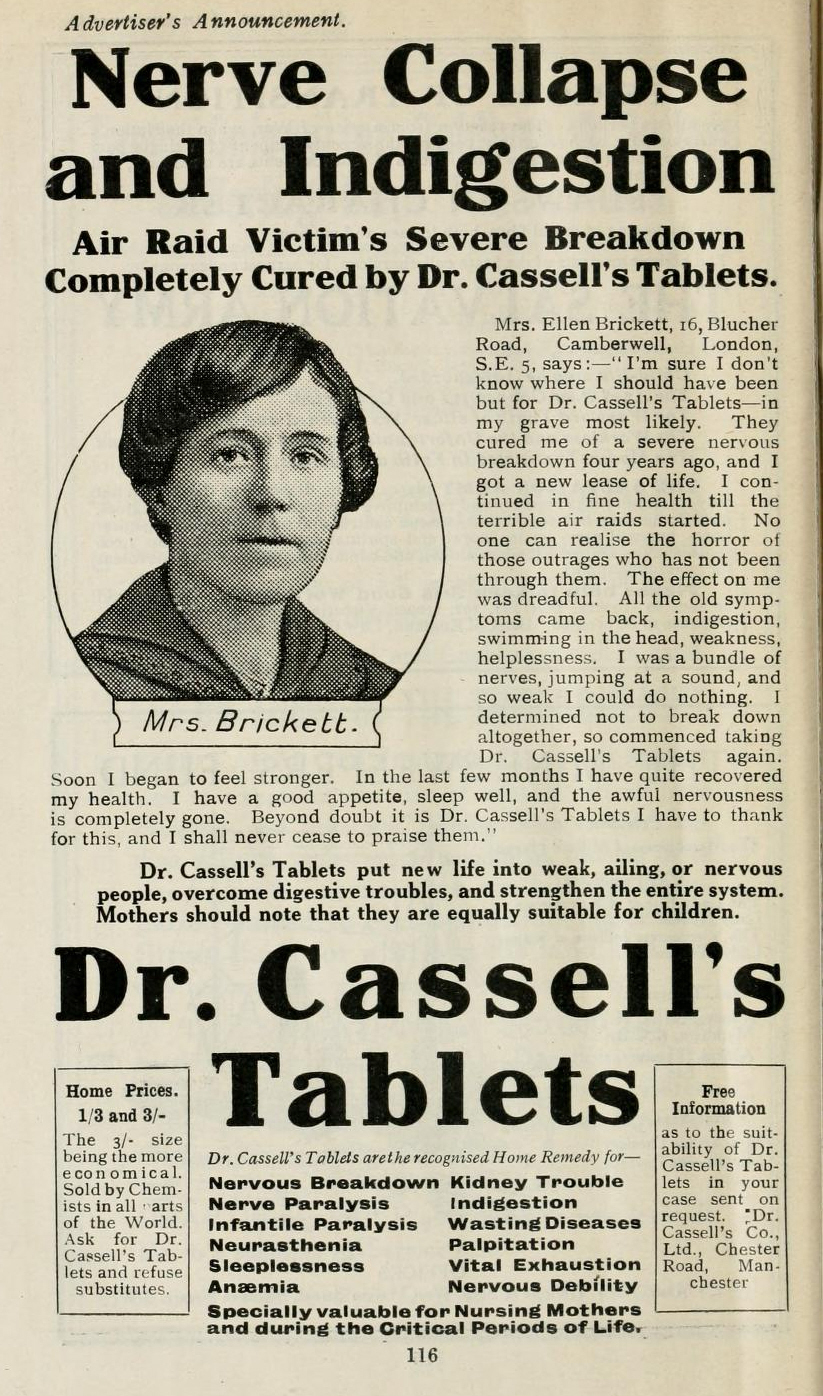

For Shell Shocked Britain: The First World War’s Legacy for Britain’s Mental Health I undertook research into the treatments available to those who were suffering from the after effects of their war service, or the impact of the war on the Home Front. The Ministry of Defence officially diagnosed 80,000 men with shell shock during the First World War, but many more suffered in silence, literally, as they returned home to a civilian life they could barely comprehend and as they struggled to come to terms with the horrors they had witnessed and the friends they had lost. Civilians coping at home also had their anxieties, manifesting themselves as ‘nerve trouble’ or uncomfortable physical symptoms – digestive illness, skin complaints, and the aforementioned headaches. When a doctor might first check the mantelpiece for his fee before beginning any treatment, a working class family found themselves good friends with their local chemist, who would supply them with an over the counter remedy such as Dr Cassell’s tablets or Phosferine.

Particular remedies were aimed at those with ailments attributable to the war itself. I found an advert for Dr Cassell’s Tablets that quotes one ‘Mrs Brickett of 16 Binker Road, Camberwell’ who swore by the pills to cure her after ‘the terrible air raids’ started. ‘I don’t know where I should have been but for Dr Cassell’s tablets‘, she says, in an advert posted in June 1919, ‘in my grave most likely.’ Another advert headlined ‘Health and Happiness’ states that the ‘Ajax Dry Coil Body Battery’, judiciously applied, can offer the man debilitated by his time at the Front relief from ‘Neurasthenia, Neuritis, Rheumatism, Sciatica, Lumbago, Stomach, Liver and Bladder troubles, Paralysis and many other complaints’.

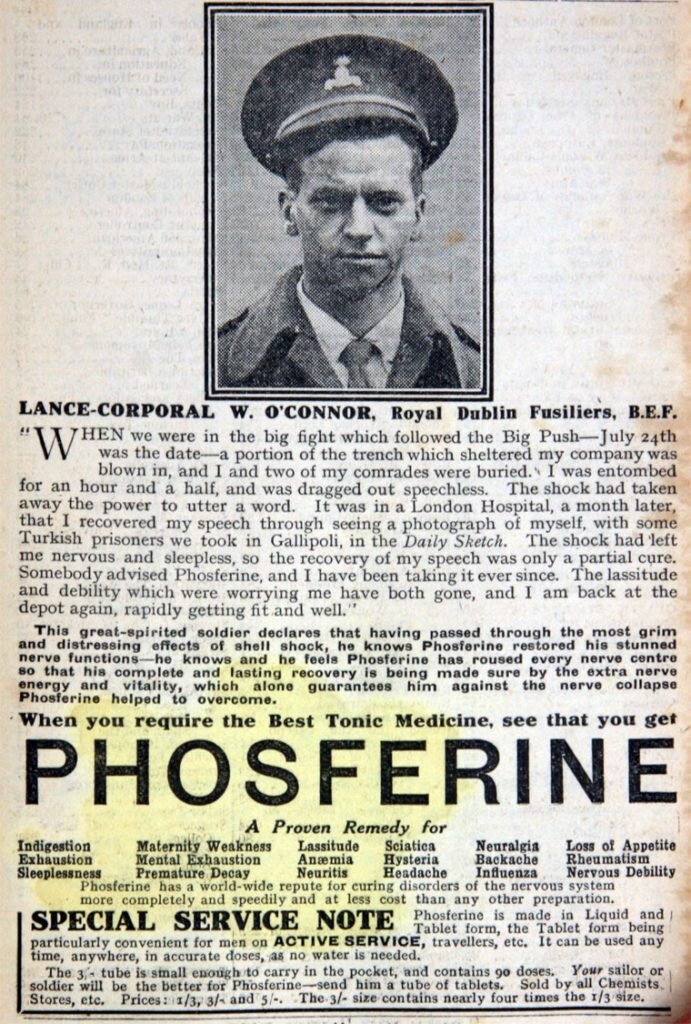

Similarly, Phosferine claimed to rebuild the life of a shell shocked man. According to a newspaper advert of 1919 R. L. Kearns, a former private from the King’s Liverpool Regiment is quoted as saying:

‘I feel that I must write a few words in praise of your wonderful preparation ‘Phosferine’ and let you know how grateful I feel for the effect produced by it in my particular case. I went to France in November 1916 and engaged in a great number of scraps with the Hun, until I was returned to England in March 1917, suffering from shell-shock. You can imagine what winter is like in the trenches, and especially to one who was never very strong.’

Many of these medicines contained substances since strictly regulated, such as cocaine and morphine, and many found themselves addicted quite unwittingly. Drug addiction and death in the wild West End of London made the headlines, as cocaine was still openly available, and the misogynist press blamed ‘loose women’ for causing addiction in the service personnel who frequented the theatres and clubs. But there was considerable low level addiction amongst the general population who required greater and greater amounts to control their pain, however it was caused.

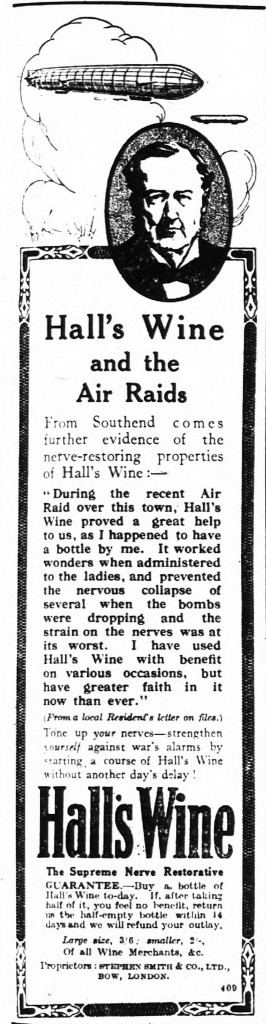

Other concoctions were based on alcohol and available from wine merchants, who might offer special rates for those returning from action at the Front. These tonics were as useful as a visit to the pub, something men also did to self-medicate, and which caused a rise in drunkenness and domestic violence. One, from 1916, is titled ‘Hall’s Wine & Air Raids’ and the advert cries out:

‘During the recent Air Raid over this town [Southend] Hall’s Wine proved a great help to us as I happened to have a bottle by me. It worked wonders when administered to the ladies and prevented the nervous collapse of many when the bombs were dropping and the strain on the nerves was at its worst’

These advertisements give a flavour of the kind of treatments people had to resort to during and after the war in order to deal with the stress and ongoing anxiety and depression. Even if a family was comfortably off and could afford a family doctor to consult when illness struck, there were few treatments available for those suffering with their ‘nerves’ as mental ill-health was regularly called in the press. Most GPs might recommend a bracing walk, or a rest cure at an expensive spa.

Many of the treatments used by specialists in the military hospitals did find their way into the treatment of the seriously mentally ill after the war, but the numbers benefiting were low. Most had to muddle on, keeping quiet about their most serious symptoms of depression and living with this enduring legacy of the First World War.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Suzie Grogan is a London-born professional writer and researcher in the fields of social and family history and mental health. Suzie’s first book Dandelions and Bad Hair Days was published in 2012 and she also writes for a wide variety of national magazines. Suzie also runs a popular blog, No wriggling out of writing, and presents a local radio show on literature, called ‘Talking Books’.

7 thoughts on “Avoiding the trickcyclist and nutpicker: First World War home remedies and miracle cures”

Comments are closed.