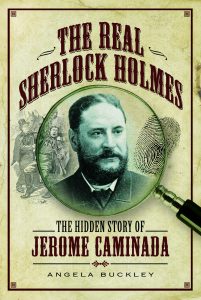

Angela Buckley’s book, The Real Sherlock Holmes: The Hidden Story of Jerome Caminada, published in March 2014, tells the story of a real-life Victorian supersleuth. In this guest post, Angela relates Caminada’s encounter with an ecclesiastical con merchant touting a dodgy elixir.

Angela Buckley’s book, The Real Sherlock Holmes: The Hidden Story of Jerome Caminada, published in March 2014, tells the story of a real-life Victorian supersleuth. In this guest post, Angela relates Caminada’s encounter with an ecclesiastical con merchant touting a dodgy elixir.

.

Urban life in Victorian England was precarious enough, but in Manchester it was downright deadly. Poor housing, inadequate water supplies and a lack of sanitation posed major hazards for city-dwellers. Killer diseases, such as typhus, influenza and cholera rampaged through the tightly packed tenements, bringing illness and death to thousands. In 1842, just two years before the birth of Detective Jerome Caminada of the Manchester City Police Force, the life expectancy of the average worker was just 18 years.

It is not surprising that people were worried about their health and, regardless of their social status, the citizens of Victorian Manchester were in a near-constant panic; a phenomenon that Detective Caminada encountered by chance one Saturday evening, on this way back from work. He was heading for home, when he popped into a pawnbroker’s shop for a quick gossip. The manager and his assistant were poring over some prints on the counter in the presence of a young man, who looked decidedly peaky. His face was cadaverous, his body shrunken and his eyes were large with fever. Suspicious of the provenance of the prints, Caminada searched the man’s lodgings and was astonished to find 153 bottles, most of which contained medicines and lotions; the desperate thief was in the grips of a quack doctor.

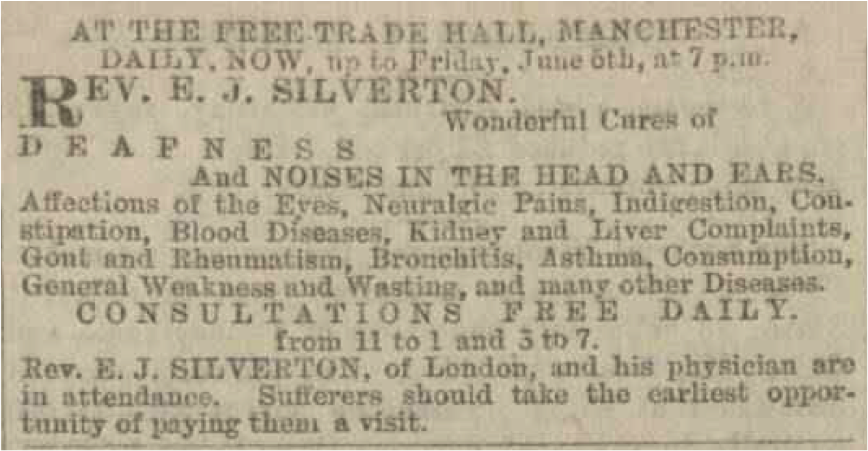

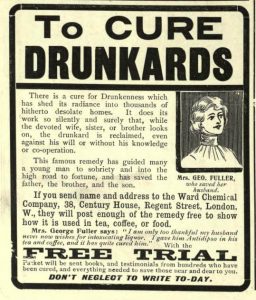

During the nineteenth century, the dubious trade of quack doctors flourished in Manchester. These expert swindlers were keen to exploit the fears of a public fully aware of their likely mortality. They ran their businesses from expensive properties on the fashionable boulevards, with handsomely furnished offices and plush waiting rooms. Their advertisements and pamphlets flooded the city, enticing passersby with their treatments for all manner of ailments. Inspired by the pitiful story of the young man, Detective Caminada set out on a quest to put an end to these ‘bloodsuckers of the human race’.

In disguise, usually as a travelling salesman or a factory worker, the undercover detective visited the premises of a number of suspects, feigning conditions, such as deafness, sweating hands and a pain in his heart. He also had concoctions mixed at the druggist’s to simulate urine samples. Invariably the ‘doctors’ offered a miracle cure at an exorbitant price, which Caminada would prove to be fake. Detective Caminada was singlehandedly responsible for the successful conviction of at least a dozen charlatans, but there was one accomplished swindler who would prove to be more than his match.

In 1877, Detective Caminada spotted an advertisement for the ‘Food of Foods’; a medicine sold by the Reverend E. J. Silverton, a Baptist minister from Nottingham. The remedy had apparently performed miracles for a variety of illnesses and was particularly effective in curing deafness. When Silverton came to Manchester, Caminada went to see the famous doctor for a consultation, dressed in shabby clothing and affecting a limp. Unfortunately Silverton wasn’t available, but the detective bought some tonic from his assistant, at a price of 35 shillings – double the average worker’s weekly wages. On analysis, the concoction proved to be nothing more than lentils, bran, brown flour and water; the ‘Elixir of all Diseases’ was a sham. Despite being arrested, the Reverend Mr Silverton slipped the net, due to legal technicalities, and continued his dishonest practice for another 20 years until his death.

Fortunately, as the conditions improved during the latter half of the nineteenth century, the need for the nefarious ministrations of the quack doctors declined. However, there were many other ruthless con artists on the streets of Manchester, as well as a ready supply of desperate victims, to keep Detective Caminada busy.

The Real Sherlock Holmes: The Hidden Story of Jerome Caminada, published by Pen and Sword Books, is now available as an ebook.

The Real Sherlock Holmes: The Hidden Story of Jerome Caminada, published by Pen and Sword Books, is now available as an ebook.

For more stories of Victorian crime visit Angela’s website at www.victoriansupersleuth.com. She can also be found on Twitter and Facebook.

3 thoughts on “Detective Caminada and the quack doctors”

Comments are closed.