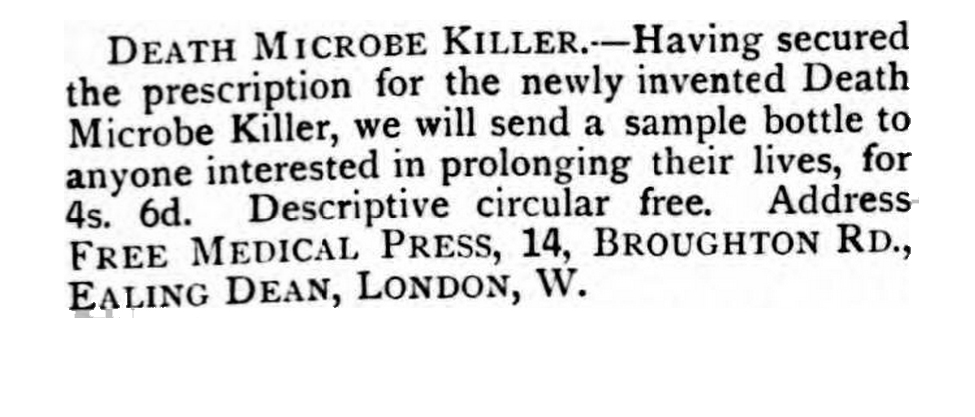

In May 1895, a low-key but intriguing advertisement appeared in British local newspapers.

What could this ‘death microbe’ be? Did it refer to the lethal pathogens such as anthrax and tuberculosis that had been identified within the past two decades? Announcements of newly isolated bacilli regularly reached the general population through the press (in 1889, someone in Paris even claimed to have found one for smallpox), and it was through the same medium that patent medicine sellers capitalised on the idea that science now had the key to ending disease. The best known germ-vanquishing remedy, Radam’s Microbe Killer, arrived in the UK from the US in 1889, using a striking visual metaphor of Death succumbing to the medicine’s might. Deadly bacteria made inroads into literature too – just a year before the above advert was published, Rudolph de Cordova’s short story The Microbe of Death featured a murderous doctor who deliberately infected his victim with anthrax.

With microbes in the cultural ether, it is not surprising that advertisements referred to them, but it turns out that the one above was promising a lot more than a cure for TB.

A story had been circulating that one Dr Wheeler of Chicago had discovered another bacillus. The new bug wasn’t a germ of disease, however; it was the ‘grand master microbe of all’ – the very embodiment of Death itself. Murderers and omnibuses could still bring an untimely end to your existence, but even the most uneventful life would at last succumb to the Death Microbe. Find the means to destroy it, and people could potentially live forever.

According to early reports, Dr Wheeler had experimented on animals and discovered that once the death bacillus was eliminated, no known disease could take hold. He was developing a treatment that would literally kill Death.

The fact that we are all still popping our clogs willy-nilly is sufficient proof that he didn’t succeed, but for a few weeks his supposed findings attracted tongue-in-cheek musings about how the human race would cope with immortality.

Overall, the newspapers did not take Wheeler’s discovery very seriously. The population, speculated one commentator, would grow so quickly that people would be forced to roam the seas in houseboats. Undertakers, gravestone masons and life insurance companies would become redundant and, without the prospect of eternal hellfire to keep us all in check, morality would go to the dogs. Another problem was that people would still grow old; the comic periodical Fun asked:

What are we to do in 2,500 A.D., with all the toothless grumbling old crones occupying not only the chimney corners, but every easy chair in the country?

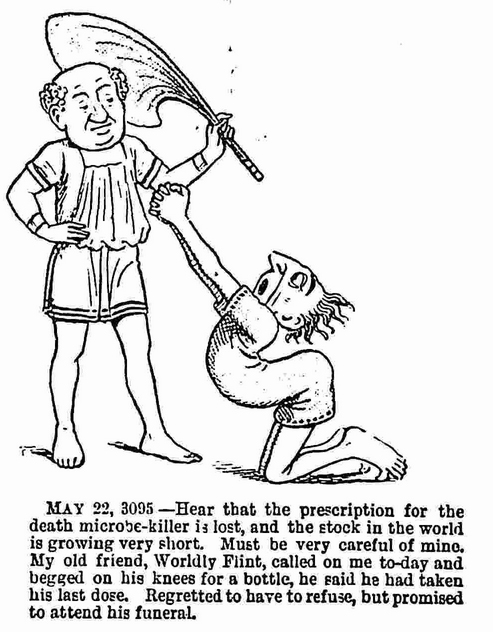

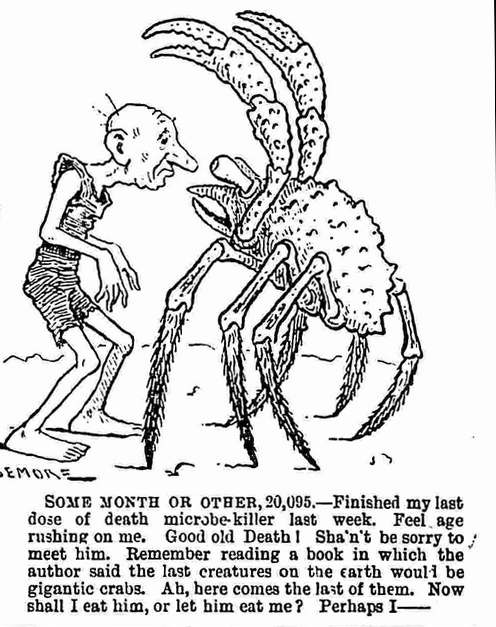

The ‘Death Microbe Killer’ adverts from the Free Medical Press ran for a few months then fizzled out, but they did inspire a science-fiction comic, Extracts from the Diary of the Last Man, in the 22 May 1895 edition of Judy: The London Serio-Comic Journal. The hero responds to the ad and buys up ‘several thousand gross’ of the Death Microbe Killer, which allow him to survive for thousands of years and go through 402 marriages before deciding to ‘remain a widower for a century or so, just for a bit of a change.’ His implied eventual demise comes at the pincers of a gigantic futuristic crab.

The discovery of the death microbe did not have a lasting impact on medicine, no doubt because it was completely made up. As The Spectator pointed out, the story originally appeared on 1 April, and was probably a prank put out by Dalziel’s News Agency. Because papers tended to lift interesting items from other publications, it continued being replicated after April Fool’s Day and the fictitious Dr Wheeler enjoyed fleeting fame before sinking back into non-existence.

A similar story popped up again the following year, with the microbe now taking the dignified name of bacillus mortis, but the means of vanquishing it remained elusive. Perhaps that was for the best. As one journalist pointed out, such a remedy could well be redundant ‘in a world where three score years and ten have often been found long enough to drink the cup of existence to the dregs.’

Sources:

‘The Small-Pox Microbe,’ The Star, Guernsey, 26 October 1889

‘The Microbe of Death’, Lincolnshire Echo, 1 April 1895

‘There is bad news today for the undertakers…’ Birmingham Daily Post, 2 April 1895

‘Getting Rid of Death,’ The Spectator, 6 April 1895

‘Frivolets’, Fun, 23 April 1895

‘Extracts from the Diary of the Last Man’, Judy, 22 May, 1895

‘The Microbe of Death’, Dover Express, 30 October 1896

————————————————–

2 thoughts on “Dr Wheeler and the Bacillus of Death”

Comments are closed.