Peoria, Illinois, 1912: the horror begins. A society lady, encouraged by a friend’s success with an easy new weight-loss treatment, pays $25 for ‘two rather large and suspicious-looking pills.’ Her husband sends the pills to be analysed by the Washington public health service, and before long a ‘government secret official’ appears, informing him that the pills contain ‘the head and first link of the body of a tape worm and sufficient nourishment to maintain life for probably a week.’

Peoria, Illinois, 1912: the horror begins. A society lady, encouraged by a friend’s success with an easy new weight-loss treatment, pays $25 for ‘two rather large and suspicious-looking pills.’ Her husband sends the pills to be analysed by the Washington public health service, and before long a ‘government secret official’ appears, informing him that the pills contain ‘the head and first link of the body of a tape worm and sufficient nourishment to maintain life for probably a week.’

It was an amazing story – the compelling revoltingness, the quack’s audacity and ingenuity; the opportunity for the timeless pastime of mocking female vanity and ridiculing the overweight. The news dispatch from Peoria brought forth some stinging commentary:

‘The fat woman who is not satisfied with the way she is built,’ opined The Charlotte Observer (North Carolina) ‘deserves no more sympathy than she will get from a tapeworm.’

More than a hundred years later, numerous websites assert that nineteenth- and early twentieth-century women merrily chugged tapeworms to mould their figures. But was this 1912 report actually true? The woman, the pill vendor and the government agent weren’t named. The only identifying detail was the mention of the Washington health service, so it was to Surgeon General Rupert Blue that the Washington Post went for comment.

‘Yes, this is the public health service, all right,’ Blue reportedly told the paper, ‘and I believe I am at the head of the service. But I have seen no tapeworm pills. The only way I have ever heard of people eating tapeworms, either wholly or in part, was by eating meat which contained them. It is a fine yarn, but simply untrue.’

Dr John F Anderson, director of the Hygienic Laboratory, said: ‘It makes me creep to talk about them. That’s the wildest story I’ve heard of for some time.’

But wild stories are difficult to tame. The tapeworm pills tale began to feed upon the digestive juices of collective revulsion, adding new segments of exaggeration with every incarnation. In 1914, a report in the Marion Daily Star (Ohio) had someone forking out $300 for a liquid-filled capsule housing ‘some form of life’. As in the 1912 version, the customer is presented as a wealthy woman whose foolishness contrasts with her husband’s sensible attempts to analyse the pills. When exercising her own agency, the woman makes a ridiculous decision – and at a time of increasingly vocal campaigns for women’s suffrage, such undermining of female capacity for independent thought does not come as a surprise.

A rubbery precedent

It was also a time when, for most people, tapeworms were not desirable companions. Itinerant specialists, using anthelmintics based on male fern, made a living helping people ditch these unwanted passengers. And from one of these practitioners comes some possible inspiration for the diet pills story.

At Peru, Indiana, in 1899, a medicine-show man named W I Swain was twice arrested for practising without a license. He allegedly gave his patients capsules containing artificial tapeworms that would navigate the digestive system and emerge as ‘proof’ that Swain’s treatment worked. Swain was acquitted, but there’s a chance this rumoured practice – not related to weight loss – became confused with the various obesity cures on offer some years later.

Avoiding the quack-busters

These cures – Marmola, Rengo, Fatoff, the Newman Cure, and many more, attracted a great deal of attention from the American Medical Association and the Bureau of Chemistry of the US Department of Agriculture (now the FDA).

These cures – Marmola, Rengo, Fatoff, the Newman Cure, and many more, attracted a great deal of attention from the American Medical Association and the Bureau of Chemistry of the US Department of Agriculture (now the FDA).

After the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, the Bureau of Chemistry clamped down on the false claims made for patent medicines, and during the same period the anti-quack investigations of the AMA’s Arthur J Cramp were being disseminated to the public as books and pamphlets such as Nostrums and Quackery. If charlatans had been selling tapeworm pills, these authorities would surely have been down on their heads so hard they’d have been nibbling their own intestinal walls. The Notices of Judgment in cases of misbranding under the 1906 and 1938 acts have been digitised and form a great resource for those of us interested in the history of proprietary medicines – not least because they contain analyses of the products seized. But no tapeworm diet pills appear among these documents. Neither is there anything of the sort in the Nostrums and Quackery books or the AMA’s pamphlet, Obesity Cures (1929 edition pictured).

A fictional friend

The tapeworm pill might have escaped these official publications, but its combination of weirdness and comedy made it perfect for The Married Life of Helen and Warren, Mabel Herbert Urner’s fictional humour column. Syndicated by papers across the US, a 1927 episode titled ‘A Get-Thin-Quick Specialist is Exposed by His Bottled Genii’ shows a character named Mrs Dodson boasting that she can eat as many potatoes as she likes thanks to Dr Phake’s system. The protagonist, Helen, is repulsed by the slippery capsules – and is even more alarmed to see one of them twitch, roll over, and jump! Given the widespread popularity of Urner’s series, it is not too much of a stretch to imagine Mrs Dodson becoming the ‘friend of a friend’ who is so often the victim of the legend.

FDA evidence

With many ‘friend of a friend’ tales in circulation, people sought answers from newspaper agony columns and from the AMA’s Bureau of Investigation. Thanks to the very helpful FDA history office, I have been lucky enough to see the surviving correspondence related to tapeworm diets. It suggests that the story kept rearing its ugly scolex but remained just out of reach of the investigators.

In response to a Mrs C Nash of Benton Harbor, Michigan, in 1930, an AMA representative wrote:

The idea that any ‘obesity cures’ contain any part of the tapeworm is a fantastic one that bobs up every once in a while and can never quite be tracked down. At any rate, we are certain that there is no truth in it.

Two years later, Prof. Francis Curtis of the University of Michigan considered mentioning the pills in a textbook, but checked with the AMA first. The reply (the file copy of which is unsigned but has a reference suggesting it was by Dr Cramp) again wrote it off as a myth:

The ‘tapeworm capsule’ for obesity is a hardy perennial. Of course, there is no such thing, and never has been. My guess is that the idea originated in the fertile brain of some newspaper man, who thought it would make a good story – and it has made a whole flock of good stories!

In the writer’s opinion, people used the legend to protect their overweight friends from getting scammed by the real obesity cure fakers.

The worm turns?

In most versions, the dieter has no idea of the tapeworm’s presence until either the pills are investigated or she leaves them on a sunny windowsill and returns to find them wriggling. But towards the middle of the twentieth century, the tale shifted to include the purposeful ingestion of parasites as a weight-loss aid. In the 1950s, Maria Callas was reported to have been installed with tapeworms under medical supervision, though she is now thought to have acquired them naturally from her diet. As Snopes notes, these rumours might have served to belittle a high-profile woman who didn’t meet society’s expectations of ‘likeability’.

The decade also brought the AMA within a worm’s breadth of finally tracking down some evidence. In 1953, they received a letter from medical ‘agony uncle’ Dr Edwin P Jordan, who had reassured a correspondent that tapeworm diet pills were ‘a wild story’, but then heard from one Dr Gettman of Hendersonville, NC, claiming that three of his patients had bought such pills from someone in Iowa. The packaging, Gettman said, stated ‘This product contains the ova of taenis (sic) saginata’. Gettman had been told by persons unspecified that the truthfulness of the labelling meant nothing could be done.

The Bureau of Investigation’s Director, Oliver Field, jumped at the chance to solve the mystery, and wrote to Dr Gettman asking for the manufacturer’s details. Even if the packaging did state the contents, he was pretty sure such a quack could be prosecuted somehow.

Alas, there is no record of a reply. Once again, the tapeworm story had slipped through the investigators’ fingers.

Eat! Eat! Eat!

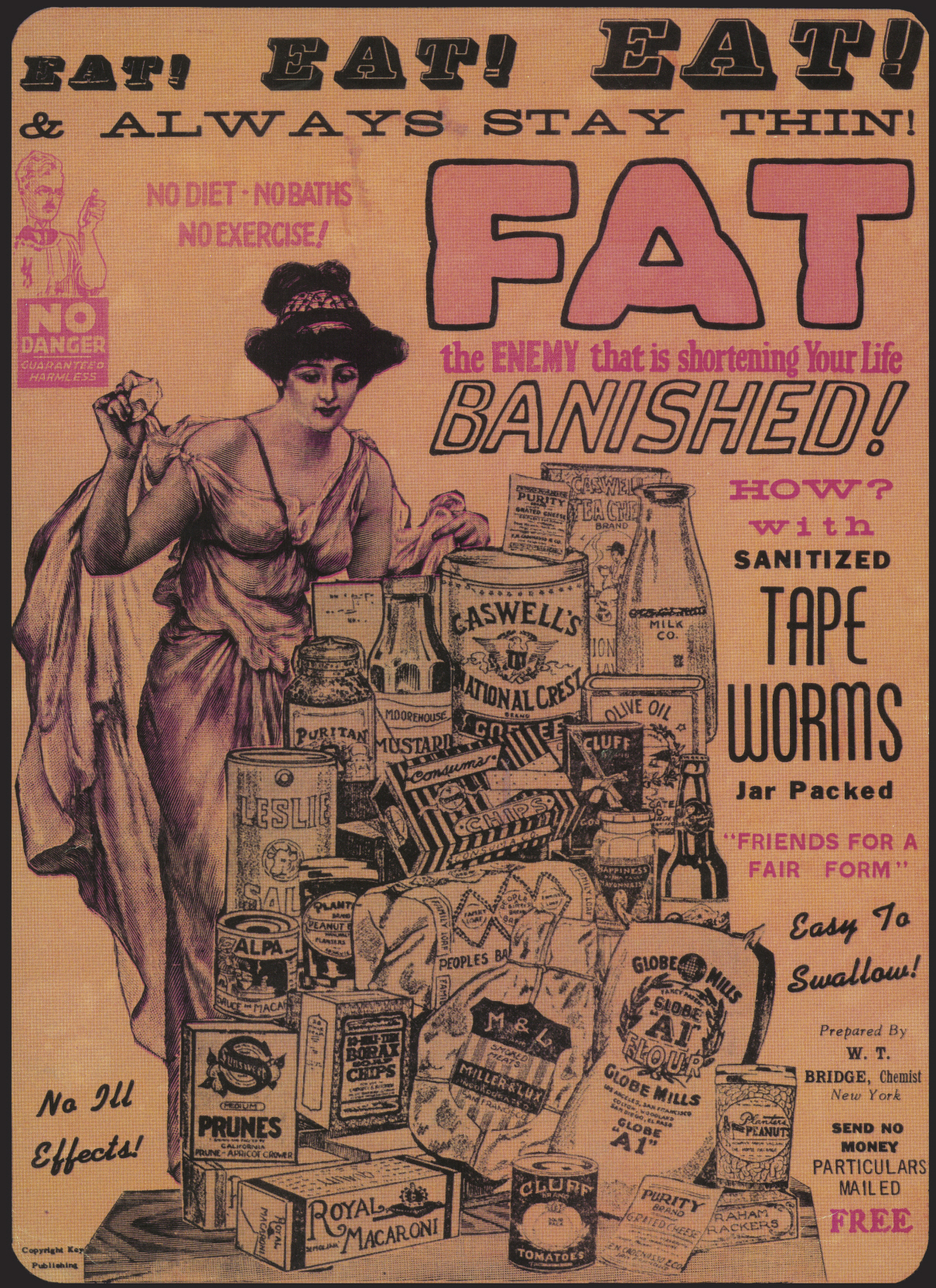

I am sure you’ve seen this image before – it’s a staple of ‘old timey cures’ listicles. And on a more highbrow level, ‘sanitized tape worms’ even make an appearance in the journal Diabetes Care, where a report on the American Diabetes Association annual meeting of 1999 refers to them being ‘widely advertised’ in the early 1900s.

Maybe one day someone will cite a convincing original source for the image, but my view is that it’s fake. Parts of the design and copy are lifted directly from 1920s advertisements for Neutroids (below), a weight-loss supplement sold by Dr R Lincoln Graham of the Graham Sanitarium, New York City.

Neutroids contained iodol, magnesium carbonate, starch, talc and a trace of iron – but absolutely no tapeworms.

Chemist W T Bridge (whoever he was – note that there is no address on the ad and 1920s New York was a big place to wander around on the chance of finding him) could, at a pinch, have recycled someone else’s advertising art, but it’s unlikely that he would have got away with using R Lincoln Graham’s likeness (right) – or, for that matter, all the brand-named foods shown in the illustration. I suspect the poster is a fun ‘vintage-inspired’ piece that has been taken more seriously than its designers intended.

Chemist W T Bridge (whoever he was – note that there is no address on the ad and 1920s New York was a big place to wander around on the chance of finding him) could, at a pinch, have recycled someone else’s advertising art, but it’s unlikely that he would have got away with using R Lincoln Graham’s likeness (right) – or, for that matter, all the brand-named foods shown in the illustration. I suspect the poster is a fun ‘vintage-inspired’ piece that has been taken more seriously than its designers intended.

Today’s tapeworms

But does this mean that no one has ever, or would ever try out the tapeworm diet? Not necessarily. Here in the UK, Michael Mosley experimented on himself for the telly (and gained weight). In 2013, a woman from Iowa supposedly bought a tapeworm off the internet, resulting in a public warning about the issue from the state’s Department of Public Health. Then last summer, Discovery Life channel’s Untold Stories of the ER reconstructed an alleged incident in which a mother infected her daughter with tapeworms to reduce her weight for a pageant – making some unrealistically squeamish health professionals do the hammiest boak-faces ever. These might just be up-to-date versions of the myth, but as The Museum of Hoaxes points out, the popularity of an urban legend can give people the impetus to replicate it. For those who are desperate, tapeworms probably sound more appealing than hearing one more person say ‘have you tried taking the stairs?’ It’s plausible that someone, somewhere has purposely played host to a helminthic fat-fighting chum.

What is less certain, however, is that commercial tapeworm diet products were on sale to our ancestors. Much as it’s fun to insist that grandma’s friend’s cousin knew someone who left some diet pills in a warm place and saw them hatch into the grotesque form of a parasite, the evidence is really rather sketchy.

Sources:

‘Bogus Tapeworms’ The Sedalia Democrat (MO), 31 October 1899

‘Tape Worms Given in Pills,’ The Washington Post, 5 December 1912

‘Tapeworm Pills for Fat People Merely a Wild Yarn, Say Experts’ The Washington Post, 6 Dec 1912

‘For Women to Read’ The Charlotte Observer, 8 Dec 1912

‘A Story with a Moral,’ The Marion Daily Star, 21 February 1914

‘Graham’s Neutroids: The Latest Thing in the Obesity Cure Line,’ Annual Reports of the Chemical Laboratory of the American Medical Association, vol. 15, 1922, pp. 33-40

Urner, Mabel Herbert, ‘A Get-Thin-Quick Specialist is Exposed by His Bottled Genii’, The Miami News (FL), 23 October 1927

Letter to the AMA from Mrs C Nash, 710 Territorial St, Benton Harbor, MI, 7 March 1930

Letter from the AMA to Mrs C Nash, 11 March 1930Letter to the AMA from Francis D. Curtis, University of Michigan, 25 March 1932

Letter from the AMA to Francis D. Curtis, 29 March 1932

‘Reducing Medicines’ Hygeia, August 1935

Jordan, Edwin P, ‘Foolish Questions Make Life of Medical Expert Interesting’ The Sarasota Journal (FL), 24 June 1953

Letter from Edwin P Jordan, MD, to Mr Oliver Field, AMA Bureau of Investigation, 18 August 1953. Includes enclosures: copy letter from R L Gettman to Edwin P Jordan, 6 July 1953 and reply from Jordan to Gettman, 30 July 1953

Letter from Oliver Field to R L Gettman, 9 September 1953

Letter from Oliver Field to Edwin P Jordan, 9 September 1953

‘Walter Winchell on Broadway’, The Times Standard (Eureka, CA), 2 March 1957

Bloomgarden, Zachary T, MD, ‘American Diabetes Association Annual Meeting, 1999’ Diabetes Care vol. 23 no. 1 January 2000 pp.118-124

16 thoughts on “‘Eat! Eat! Eat!’ Those notorious tapeworm diet pills”

Comments are closed.