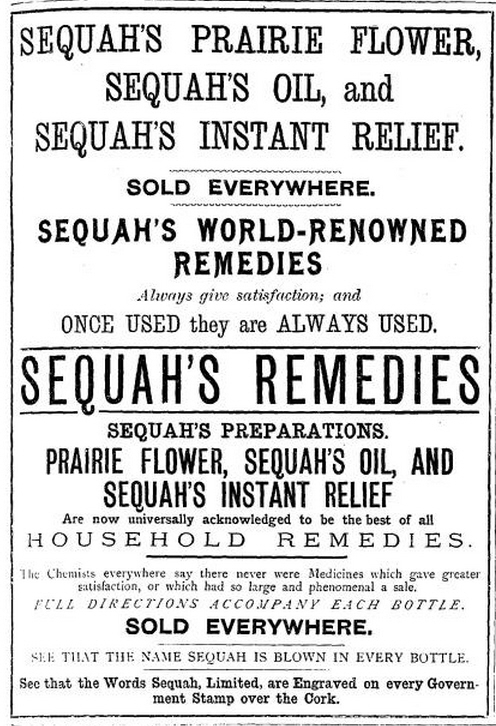

Source: The Graphic 11 July 1891

Source: The Graphic 11 July 1891

.

From the moment of his sudden rise to fame in Portsmouth in 1887, Sequah knew how to win friends and influence people. He built up an almost cult-like following by giving the crowds what they wanted – miraculous cures, affordable medicines, and a lot of Wild West-style entertainment.

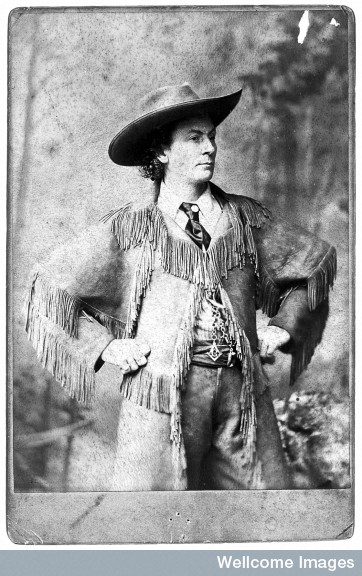

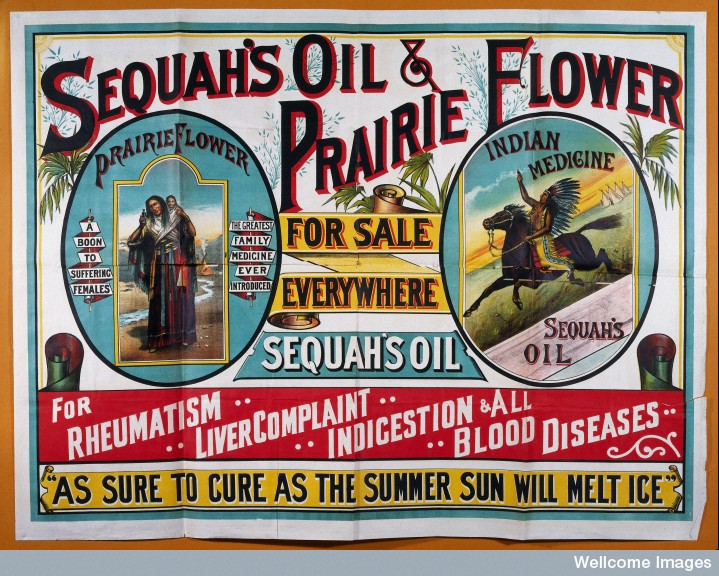

Handbills and extensive newspaper advertising built up the hype, so that when Sequah arrived in town, a curious crowd would be waiting for him. His painted wagon, brass band and entourage of assistants dressed as cowboys and Indians made for an unusual spectacle, and his displays of speed dentistry would get even cynical audience members cheering.

For all Sequah’s Western get-up and claims about the traditional Native American origin of his recipes, he was a Yorkshireman called William Henry Hartley. About a year after he began his shows, demand for his products – Sequah’s Prairie Flower and Sequah’s Oil – proved so high that he needed to be in two places at once, so Hartley recruited some more ‘Sequahs’ to cover different areas of the country. By late 1890 there were 23 of them, and Sequah grew to be a big-business brand name throughout Britain and Ireland.

Getting the audience on side was a vital part of Sequah’s modus operandi. The entertainment provided by his apparent tooth-drawing expertise was just the prelude to the main part of the show. Rheumatism sufferers would be carried up on stage to undergo a theatrical process of massage with Sequah’s Oil. Afterwards, they walked jauntily away, apparently cured.

It sounds a con, but these patients were not shills – they were local people known to others in the crowd. One example is Michael Casby of Sheffield, who informed Sequah that he had suffered from rheumatism for 16 years. Consultations with numerous doctors had been to no avail so Sequah’s attendants carried him forward for treatment. Soon the pain had gone, and Casby and Sequah danced a jig together.

One audience member, John Roadhouse, was suspicious. He asked around and discovered that Casby was an outdoor labourer on the Duke of Norfolk’s Sheffield estate. He had missed only half a day’s work in the past three months, and his colleagues expressed surprise that he had been carried onto the stage, as they had never known there was anything wrong with him. Casby later tried to explain away his actions by saying he had knee pain. His motivation appears to have been to buy into the hype surrounding Sequah and become part of the performance. For other patients, the collusion with the theatrical atmosphere was probably subconscious – caught up in the excitement, they might exaggerate their condition and play to the audience’s expectations of a cure.

Above: Sequah pulls a tooth while his brass band plays in the background. The bulb on his forehead is an electric light. Cheshire Observer 15 March 1890

.

Sequah also insinuated himself into influential people’s good books by giving money to local charities, but there was one group he did not get on with – medical students.

In Edinburgh in 1888, a note travelled round the University’s medical department suggesting a demonstration against Sequah (the original one). At Waverley Market that night, according to the Dundee Courier & Argus, Sequah was ‘greeted by a considerable number of young men with jeers and cries of “Quack.”’ Allegedly, one of them leapt forward and coshed a performer (possibly Sequah himself) with a stick. The assaulted party retaliated and knocked him out, to the delight of the crowd, who began shouting ‘Down with the students!’ The disturbance must have been anticipated, however, because the police were out in force and used ‘energetic measures’ to quell the kerfuffle and haul the students away.

Police involvement was a regular occurrence at Sequah shows, but they were not always so heavy-handed. In 1889 a police sergeant managed to rescue one unfortunate young man when the crowd turned ugly on him. The show included a ‘thanksgiving’, where former patients were invited to testify to the power of Sequah’s treatment, but once the man got up on stage, he said what he really thought about its failure to cure him. On his return to the crowd, he was set upon and had to be pulled back onto the wagon, where the sergeant also scrambled up to protect him until the show was over. Afterwards, a mob followed the wagon as far as the police station, shouting ‘Lynch him!’ Once inside the charge office, the frightened chap managed to escape via a side door, having learnt that upsetting a quack’s loyal followers can be a matter of life and death.

.

There is a vast quantity of surviving evidence pertaining to Sequah and his medicine company – enough, in fact, to fill a whole book rather than a blog post, so it’s possible that Sequah will show up again on The Quack Doctor. For further reading, however, I can highly recommend W. Schupbach’s paper, Sequah: An English “American Medicine” Man in 1890, which is available at PubMed Central.

.

.

What a fascinating, wonderful post – I totally enjoyed reading about Sequah and all the other Sequahs. And the illustrations are also quite fab! But… I wonder how he kept the light bulb on his forehead?

It does look as though it’s embedded in his skull! The beams are also blocking out the bodies of the brass players, making them reminiscent of artistic interpretations of angels – whether that’s intentional or not, I don’t know.

In checking on my family history I am a direct descendant on Charles Frederick Rowley who was widely known as “The Great Sequah”, he was an entrepreneur of his time. During our research we found that he died in New Zealand where he had become a national figure and is still revered there today. It is said that the brass band played as loud as possible in order to drown out any screams from the patients having their teeth pulled.

Hi Keith, we haven’t met for yonks.

Please get in touch so we can share our findings. I don’t know about you but I’ve nearly got a life history to sort out, even what he did in World War I

We soon won’t have anyone to share them with.

I hope you manage to get in touch with each other and share what you’ve found out.

Caroline

Hi, Thanks for posting the Sequah info. I am the great grandaughter of one of the most successful of the Sequah’s, one William Francis Hannaway Rowe. William and William Henry Hartley frequently get muddled up by writers on the subject. Hmm Quack Doctors.. William was a herbalist and also believed in massage as an effective theraphy. Prarie Flower contained fish oils and herbs that are now lauded today for good health..I can imagine what he would say about the goings on of “Big Pharma” in the 21st centuary

Hi Gillian – thanks for commenting. How cool to be descended from a Sequah! Do you have any documentation pertaining to his life? I wondered if the Sheffield Sequah referred to above was Rowe as he was covering other parts of the north east at the time.

Do you know if it’s true that he was a dentist as well as a herbalist before teaming up with Hartley?

Thanks

Caroline

Hello..yes its pretty cool..and yes I have a very good deal of info on William and the other Sequahs and a good collection of the medicine bottles.. I am happy to share what I know and there are descendents of other Sequahs knocking about as well. I am not sure that William was a dentist prior but I am sure he was what might be described as a “medical botanist” and in later years he wrote and self published a book on Massage..please feel free to contact me on the email I gave and I can respond at length if you wish

My great grandfather was the greast sequah and was a dentist. he pulled teeth in the back of his wagon. he also had patent for the first electric pain killer. We have researched great grand father and found masny reports of him. He sold his home in Kew, London, and left his family and emmigrated with his new lady friend to New Zealand. I believe he died there. His name was George Fredrick Rowley. if anyone in NZ has any information about him I would to hear from you.

I’ve been interested in Sequah (William Hartley, the original one) for years, and give talks about him – I’m a medical historian. I’ve recently been doing some more detailed research on him, and am wondering whether he ever gave a truthful account of his life to anyone, including his own sister! I do know that he was born in Liverpool, but arrived in Yorkshire aged 2-3, with his mother, to live on his father’s father’s farm, although his father stayed in Liverpool. But it’s difficult to verify much after that – he was a great storyteller and showman, and clearly had the gift of the gab, that’s for sure.

Hi,

Does anyone have a date when Sequah’s show visited Peterborough please?

Thanks

Les

Hi Les,

I’ve had a look on the British Newspaper Archive and Sequah’s advertisements suggest there was a visit to Peterborough for three weeks at the end of October and beginning of November 1889.

Best wishes,

Caroline

I too am interested in the peterboro show, I’m just researching my partners 3rd great granddad Alfred windle Hawksworth. ive discovered he wrote a testimony in the Lincolnshire free press in nov 1889 thanking sequah for his miracle cure for his wife (who it sounds like was going through ‘the change’)

he actually carried one of the lame to the stage to be treated.

thanks for this blog