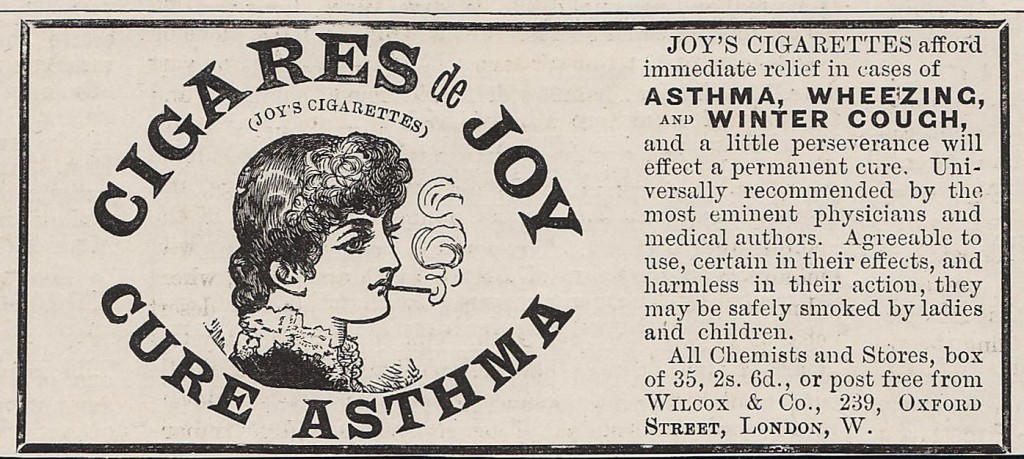

While browsing your local newspaper in the 1890s, an asthma-cure advertisement might distract you from tales of the latest sensational crimes. ‘Agreeable to use, certain in their effects, and harmless in their action, they may be safely smoked by ladies and children,’ ran the promotional copy. The product was Cigares de Joy, handy little cigarettes designed to smoke out those lung problems and give you a new lease of life.

The Victorian asthma cigarette epitomises some of the common responses to what I (attempt to) do here at The Quack Doctor. A fictional but representative dialogue might go somewhat as follows:

The Quack Doctor: ‘Asthma cigarettes were recommended by nineteenth-century doctors as a convenient way of administering drugs directly to the lungs.’

Response 1: ‘Nope. Not quackery at all. Actually, asthma cigarettes were actually recommended by actual doctors as a convenient way of administering drugs directly to the lungs, actually.’

Response 2: ‘LOLOLOLOL WTF asthma cigarettes! Those crazy Victorians were so gullible! LOOOLLLL.’

It’s true that there’s now a humorous incongruity in the notion of smoking for health, but the asthma cigarette formed part of a long history of inhalation therapy that continues in the familiar medications of today.

Ancient systems of medicine interpreted asthma within the context of the four humours – the qualities of blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile, whose balance was deemed responsible for the health of the human body. Within this framework, asthma resulted from a build-up of phlegm in the lungs, so it made sense to send medicine straight to the affected part by advising the patient to inhale the smoke of burning herbs.

Interpretations of asthma changed over the centuries and inhalation fell in and out of favour, but by 1800 it had become known as a ‘nervous’ disease caused by spasms of the bronchi. One of the main ingredients in the later asthma cigarettes – stramonium – began to take off in Britain in the first decade of the nineteenth century.

Datura stramonium, or thorn-apple, already had a following in the US, but its British popularity began as an alternative to similar treatments learnt from Indian medicine during the East India Company’s control over the subcontinent.

Indian doctors used the plant Datura ferox in the treatment of lung conditions. After an East India Company physician brought samples to London sometime between 1802 and 1810, surgeon Joseph Toulmin of Hackney – himself asthmatic – recognised that there might be an effective remedy closer to home. He substituted D. stramonium and found his own asthma much improved. Word about the new remedy quickly spread.

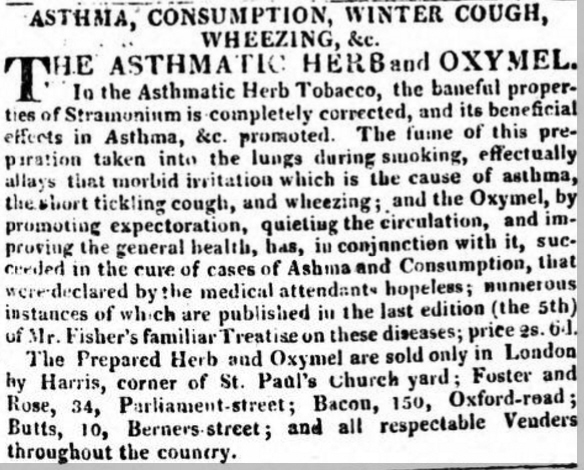

At first, stramonium was smoked in ordinary tobacco pipes. You could grow it yourself and prepare the roots and stalks (not the leaves, which have a dangerous narcotic effect) by drying them, brushing off the mould and chopping them into small pieces. Even so, commercial dealers cashed in – in 1811 the Belfast Monthly Magazine claimed that stramonium fetched 24 shillings per pound in London, when you could previously have got a big bunch for threepence. As soon as Mr Toulmin’s advice gained publicity, a surgeon called J T Fisher brought out a blend of Asthmatic Herb Tobacco (though this was considered rather disreputable by proponents of pure stramonium.)

By the middle of the nineteenth century, smoking in general was a big thing – socially acceptable, manly, and becoming ever easier with the introduction of cigars, cigarettes and matches. Henry Hyde Salter, a leading authority on asthma, advocated the use of ordinary tobacco, provided the patient was not already a regular smoker. Tobacco would induce a state of ‘vertigo, loss of power in the limbs, a sense of deadly faintness, cold sweat, inability to speak or think, nausea and vomiting.’ This might be unpleasant, but in Salter’s experience it would halt an asthma attack. In his 1860 book, On Asthma, Its Pathology and Treatment, Salter discussed stramonium as well, advising its regular use as a preventive. He, however, acknowledged that people’s experience varied, and ‘one patient says he would as soon be without life as without stramonium, another might as well smoke so much dried cabbage leaves.’ By this time, ready-prepared stramonium cigarettes (and belladonna ones, too) were available over the counter and were also prescribed by doctors. Although not everyone was a fan, such products were not generally considered quackery in their time.

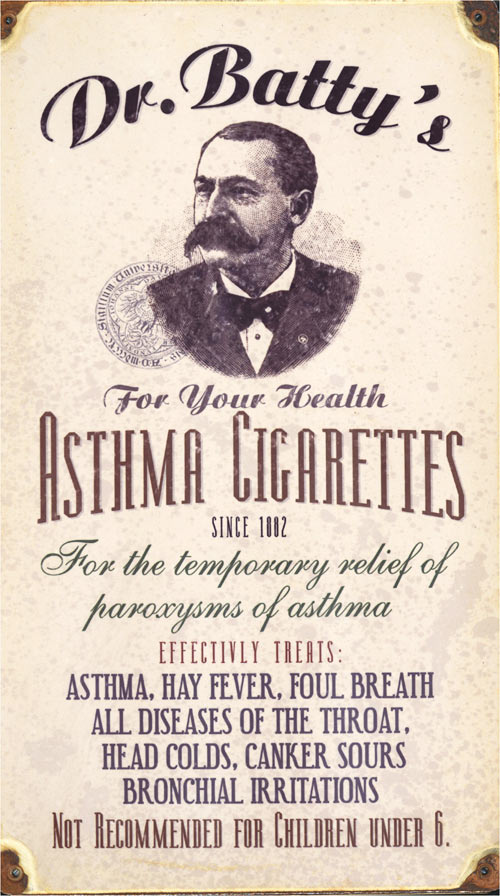

It’s interesting, therefore, that an asthma cigarette advertisement has become one of the go-to images for the modern illustration of Victorian quacks.

This sign pops up frequently on the internet, but although it is inspired by real products, Dr Batty is a myth – it’s one of those ‘vintage-inspired’ fun things like the ‘Sanitized Tapeworms’ ad I have written about before. As well as the modernity of the typefaces, the warning ‘Not recommended for children under 6’ is anachronistic – Cigares de Joy and their ilk specifically advertised their suitability for children as an illustration of their harmlessness. This 2010 metafilter discussion features someone saying they designed it.

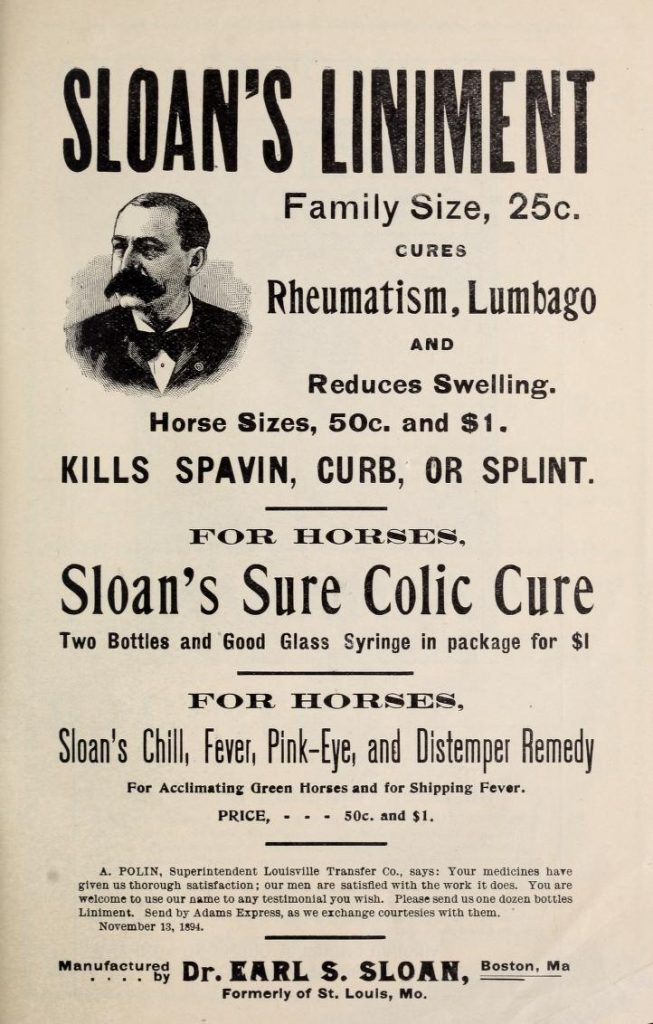

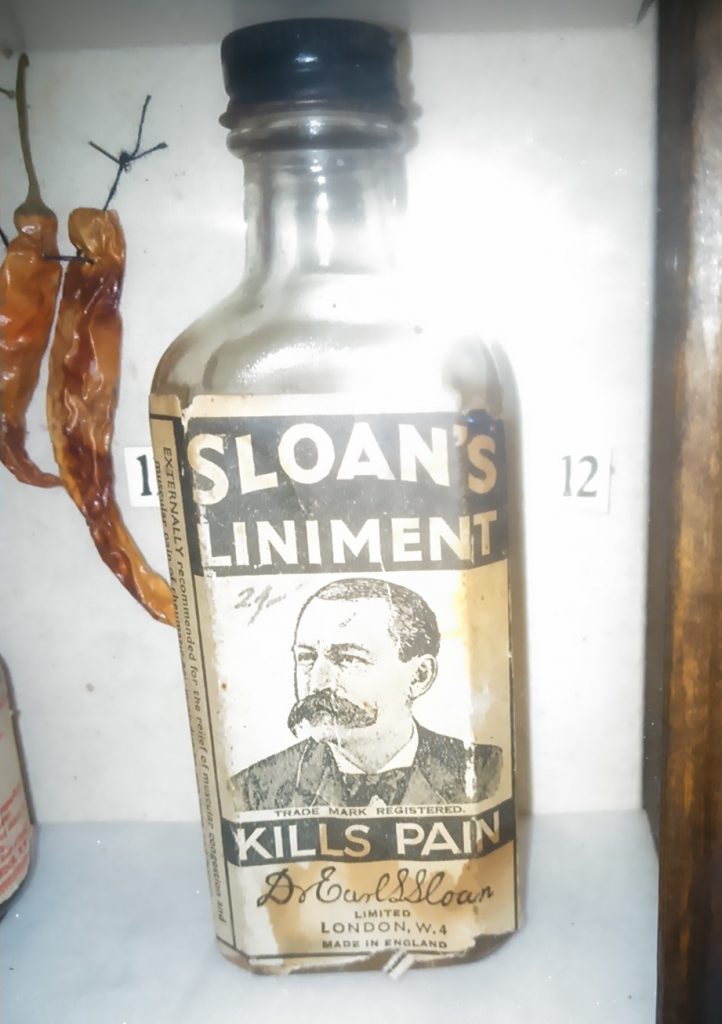

But one thing that, as far as I am aware, hasn’t attracted attention in discussion of the sign’s provenance is the ‘Dr Batty’ portrait itself. It is borrowed from a real American patent medicine man, Earl Sawyer Sloan (1848-1923). Sloan’s Liniment – a topical application introduced in 1871 for horses and later marketed for humans too – carried its proprietor’s image on every bottle and packaging container. Sloan became a millionaire through sales of the liniment and related products – he would certainly not have put up with some upstart Dr Batty geezer claiming ownership of that fine moustache.

In the early twentieth century the spasmodic model of asthma gave way to the concept of allergic inflammation, and this made smoking less appropriate. At the same time, new drugs such as ephedrine emerged, providing an alternative to the potentially hallucinogenic stramonium. Changes in cultural attitudes to smoking and confirmation of its link to cancer, along with new medications (e.g. salbutamol in 1969), saw stramonium disappear from the arsenal against asthma – but its Victorian cigarette form had played an important role in bringing relief to those struggling to breathe.

Sources:

Anon, ‘On the use of Stramonium in Spasmodic Asthma,’ Belfast Monthly Magazine, March 1811

Anon, ‘On Stramonium’, The Medical and Physical Journal, vols 25 and 26, 1811.

Salter, Henry Hyde, On Asthma, its Pathology and Treatment, London, 1860.

Sills, Joseph, Communications relative to the Datura Stramonium, or Thorn-Apple, as a Cure or Relief for Asthma, London, 1811.

Jackson, Mark, ‘”Divine Stramonium”: The Rise and Fall of Smoking for Asthma.’ Medical History 54.2 (2010): 171–194.

If I’m not mistaken, Native Americans smoked Mullen for relief of asthma and other lung issues due to its action as a bronchial dilator.