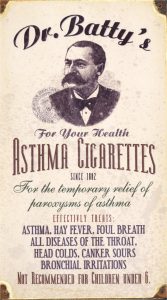

In early 20th-century New York, a mailman introduced a new patent medicine called Health Grains for indigestion – but the ingredients were far from beneficial.

Mrs Bertha Bertsche, a 38-year-old widow, could often be found supervising the pans on the kitchen range at her home in Glebe Avenue, Westchester Square, New York. Inside the pans, however, was no hearty stew or bubbling jam. At the request of her lodger, Jacob Selzer, Mrs Bertsche was using the range to dry a substance of very little culinary appeal.

Jacob Selzer lived on the upper floor of Mrs Bertsche’s house, bringing her some much-needed income for the support of her five children. He was a courteous and conscientious letter-carrier with the Westchester postal station, but once he got home from delivering the mail he worked on his own business venture – that of a patent medicine proprietor. The substantial sounding ‘Health Grains Co. of Westchester’ was just him, with help from his landlady.

Health Grains targeted ‘Dyspepsia, Indigestion, Nervousness etc.’ and letters found in Selzer’s rooms suggested that he was sending them out to customers all over the US. Unfortunately, there don’t seem to be any surviving pictures of the advertisements or packages, but a report in the Journal of the American Medical Association gives some idea of the content of Selzer’s circulars:

‘Do not chew or grind Health Grains between the teeth, but roll them around slowly until they have become saturated with saliva, then swallow them. One scant teaspoonful constitutes a dose. Take one or two doses after a light meal, two or three after a heavy meal. Doses should be taken separately. If your stomach keeps you from sleeping, take from one to three doses. Do not overeat. Avoid eating what you know disagrees with you.’

The dangerous-living investigators at JAMA ignored the warning about not chewing. They tried consuming the Health Grains and found that: ‘when ground between the teeth they exhibit unmistakable signs of hardness.’ The product had ‘the appearance of coarse sand covered with a sticky substance’.

Unsurprisingly, it turned out that it was coarse sand covered with a sticky substance.

Selzer had offered Mrs Bertsche 75 cents a day to wash and dry ordinary quartz sand in her kitchen – a thoughtful nod to hygiene there, as heaven forbid the valued customers should find dirt in their sand. He then mixed it with melted rock candy and maple syrup, which hardened to form a sweet crunchy substance. This was presented in round tins wrapped in a paper guaranteeing that ‘the contents of this package complies with the Pure Food and Drugs Act’. The price was $1 per tin.

The sands of time at last caught up with Jacob Selzer and he died in November 1908, which brought the Health Grains Co to an abrupt end. It was only after his death – and the discovery of his very healthy bank accounts – that his activities came to light and the composition of the product revealed. JAMA’s verdict on this unusual medicine was characteristically deadpan. Health Grains showed:

‘…an originality of composition surpassed only by the credulity of the consumers of such a nostrum.’

‘Fortune Built on Sand‘, New York Tribune, 27 Nov 1908.

‘Health Grains’, Journal of the American Medical Association, c.1 v.52 Jan-Jun 1909.

‘New Patent Medicine Advertising Fakes’, The Sterling Kansas Bulletin, 11 March 1910.

Stock photo by @jack_ol on FreeImages