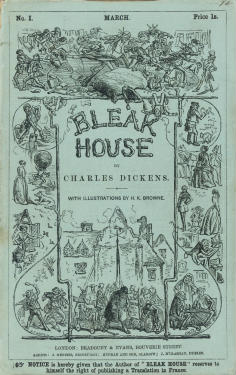

Between March 1852 and September 1853, monthly instalments of Bleak House tempted readers with their eyecatching illustrated covers and affordable price of one shilling.

Within these covers, the ‘Bleak House Advertiser’ promoted commercial products, from new publications to false teeth and from wigs to bedsteads. Inserted in part fourteen, however, after chapters 43 to 46, was an 8-page advertisement containing a narrative creation of its own.

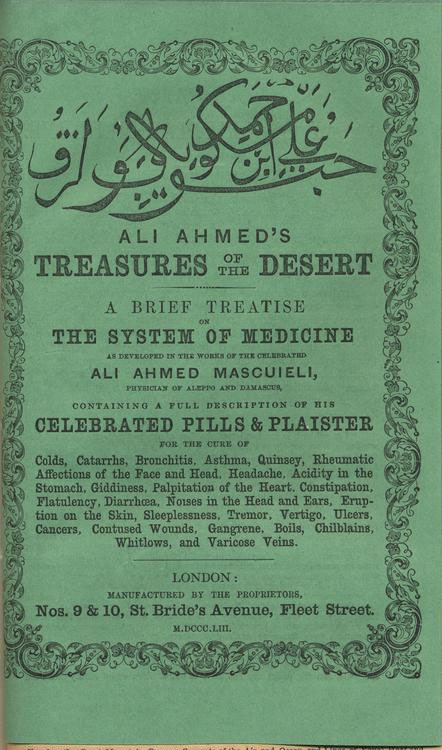

Ali Ahmed’s Treasures of the Desert were a set of three remedies whose proprietor created an aura of eastern mystique to present them as traditional and natural alternatives to harsh western medicine. The range comprised the Sphairopeptic Pill for liver and digestive complaints, the Pectoral Antiphthisis Pill to fight off colds, asthma and consumption, and the Antiseptic Malagma – a plaster for use on ulcers, wounds and gangrene. With a month to wait until the next instalment of Bleak House, readers probably went back to the advertising inserts as stop-gap reading material, and the advertiser therefore had the opportunity to get them on side by offering more than just a hard sell.

The pamphlet draws the reader in with an unexpectedly up-front reference to quackery:

WHAT! more atrocities in the quack line? More conspiracies against the poor stomach? Such we can easily believe to be the exclamation of the reader as he scans the heading of this paper.

It’s all very well to think that when you’re in fine fettle, however. The pamphlet goes on to remind us that we might suffer health problems in the future and would do well to keep these remedies in mind.

Ali Ahmed Mascueli was supposed to have been a Persian physician, who spent most of his life in Syria and developed the remedies using local herbs. On his deathbed, he confided the recipes to his relatives, who handed them down through the generations until, in the 19th century, they attracted the attention of ‘an excellent and philanthropic Englishman’ who saw it as his duty to share them with the world. The pamphlet used a decorative border and examples of calligraphy (described by Bernard Darwin in his 1930 book The Dickens Advertiser as ‘lovely Arabic curly-wiggles’!) to lend an air of exoticism, emphasising the long tradition of eastern medicine from which the remedies had sprung.

Ali Ahmed’s Treasures of the Desert – cover of advertising insert. Image credit: http://www.ibiblio.org/dickens/html/42058.html

After a brief introduction, the pamphlet features a letter from a friend of the proprietor in Damascus, who had introduced the remedies there to the fury of the resident French and Italian doctors. The letter writer becomes a ‘character’ in the pamphlet’s narrative, entertaining the reader with a tale of a doctor so incompetent that he once ordered a large supply of sodium chloride, believing it to be a medicine.

In preference to such ‘scientific’ idiots, the letter-writer lauds ‘the simple native physician,’ whose drugs are ‘the kindest gifts of nature to suffering humanity.’ Unlike the violent substances such as strychnine and morphine prescribed by European doctors, the eastern practitioner’s drugs are ‘simple and pure; the mountainside furnishes him with herbs and roots, and the plains are bountiful in bulbs.’

The notions that a remedy stems from ancient, traditional knowledge, that it is safe and natural, and that narrow-minded orthodox doctors hate it are all, of course, to be found in dubious advertising today.

Punch pointed out that the medicines would probably work if taken as part of the lifestyle enjoyed by Ali Ahmed. Together with a sparse diet, only water to drink, and plenty of horseback exercise, they would no doubt remove ‘the worst congestion of the liver that ever affected alderman.’

So, just how exotic were these medicines? Cooley’s Cyclopaedia of Practical Receipts, Processes, and Collateral Information in the Arts, Manufactures, Professions and Trades, including Medicine, Pharmacy and Domestic Economy (Fourth Edition 1864) gave the ingredients as follows:

The Antiseptic Malagma comprised lead plaster, gum thus (frankincense or, more likely, thickened turpentine), salad oil and beeswax, spread onto calico. The Pectoral Pills were myrrh, squills, ipecacuanha, white soft soap, aniseed oil and treacle, while the Sphairopeptic Pills contained aloes, colocynth pulp, rhubarb, myrrh, scammony, ipecacuanha, cardamom seeds, soft soap, oil of juniper and treacle. The advertising also claims that the pills were ‘silver-gilt in the Oriental style’, a practice traditionally thought to have originated with tenth-century Persian physician Avicenna.

Ali Ahmed, from an advertisement in vol. XV of Bleak House (May 1853) Image credit: http://www.ibiblio.org/dickens/html/42059.html

In celebration of the bicentenary year, The Quack Doctor plans some further posts tenuously related to Charles Dickens, so look out for them on the blog soon. In the meantime, happy 200th birthday, Mr. Dickens!

a real treasure trove!