On 19 January 1838, the steamer Killarney set sail from Cork, bound for Bristol. On board were 37 people and 600 pigs, and ahead of them was the most violent storm in more than half a century. The steamer was forced to turn back, and anchored at Cove for a few hours, until the Captain made the ill-fated decision to continue. By the following evening, 21 survivors were clinging to a rock, fast losing hope of rescue.

One of these survivors was Baron Spolasco (above), a flamboyant character who had been fraudulently practising as a physician and surgeon in different parts of Ireland. Though he looks rather exotic, he was probably born in the north of England in about 1800, and his real name appears in different sources as John Williams, John Smith, or the slightly more impressive John William Adolphus Frederick Augustus Smith.

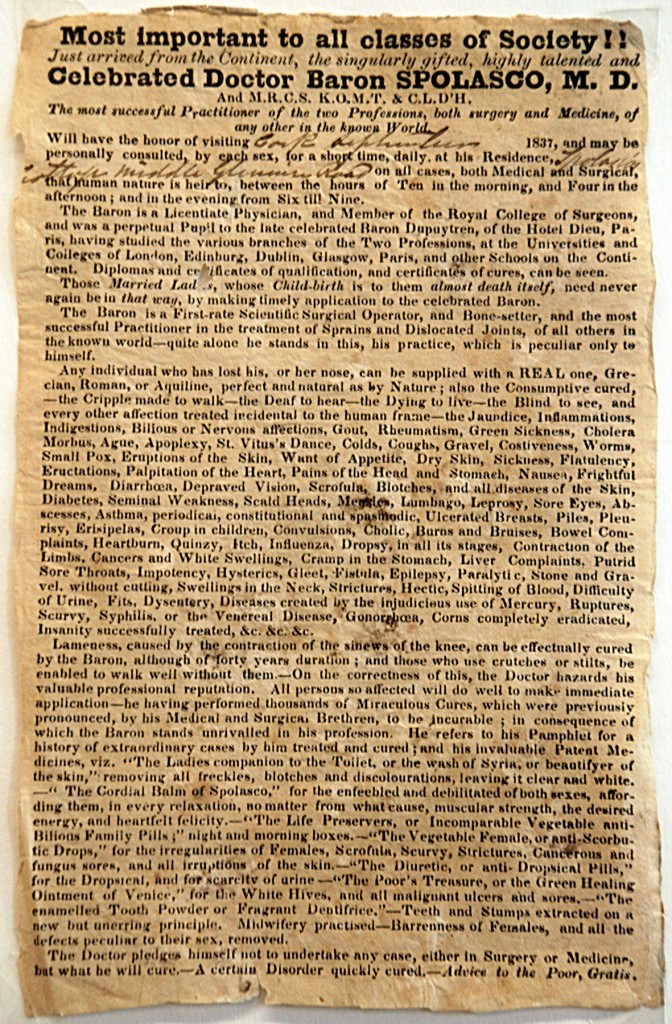

Spolasco did not specialise in particular ailments – he cured everything instantly. You can click to enlarge this handbill and see the extent of his claims. I am very grateful to Lucy Martin for the handbill and portrait photographs, which she took at the University of Cork Art Gallery.

One part of the handbill says:

Any individual who has lost his, or her nose, can be supplied with a REAL one, Grecian, Roman or Aquiline, perfect and natural as by nature

This was done by the Talicotian operation, an ancient and ingenious way of reconstructing a missing nose by bringing down a flap of skin from the patient’s forehead.

On that fateful Friday in January 1838, Spolasco was off to Bristol to meet the agent of a ‘high personage’ about a complicated surgical case (or perhaps the people in Cork were starting to get wise to him). All his belongings were loaded onto the Killarney but he, his eight-year-old son Robert and their two Newfoundland dogs were five minutes late. They had almost resolved to wait for the next week’s boat, when some locals offered to row them out to the steamer.

During the course of that night and the next morning, the storm and the terrified pigs put the steamer in peril and it perished in Renny Bay. The poor Newfoundlands rapidly joined the choir invisible, but the Baron and Robert were among the 21 people who reached a rock 200 yards from shore. Though so close to land, there were no rescue attempts until the Sunday, by which time little Robert was among those who succumbed to the waves. In his Narrative of the Wreck of the Steamer Killarney, Spolasco later described his feelings about the death of his son:

I pause one moment to offer up my most fervent supplications to my God, to spare such of you my kind readers, as are fathers, and mothers; to spare you ever, from having to go through, to witness, to feel, to suffer, even a thousandth part of what I did for my dear, my sweet, my beautiful boy. Alas ! he is now no more, he is as still as the grave ! yes he is quiet—he moves not—he breathes not—he no longer enchants me as he was wont to do, morning, noon and night, with his sweet prattling, his but too sensible conversation ! HE IS DEAD ! ! !

The Narrative is a gripping read and, while melodramatic (in a good way) and self-aggrandising, the Baron’s story concurs in most details with other reports of the wreck.

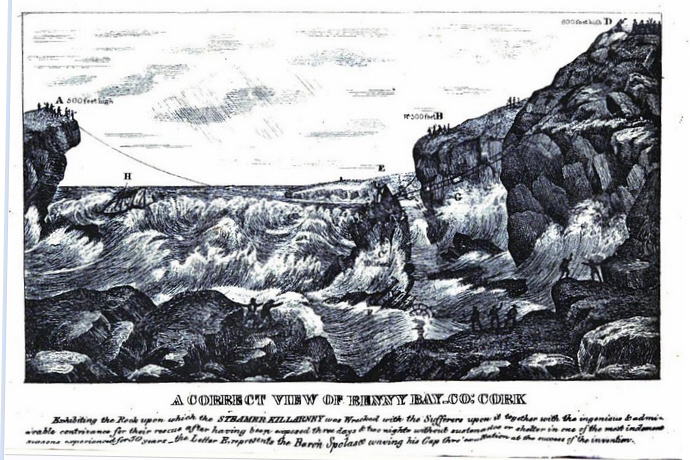

The image below is from the Narrative, and though there’s no doubt a bit of artistic licence, it does emphasise just how near and yet so far the stranded people were from the land. They could see the locals making off with the dead pigs washed up on the beach, but they could do nothing to get themselves there alive.

We had not the good fortune to reach the top of the rock; we only got to between one and two yards of it and that part faced the sea. We had to hold on all night by our fingers and toes – something like being suspended by our hands and toes from the sill of a window in one of the upper stories of a house, and at every moment the tremendous and fearful billows lashing at our backs terribly, we were not able to rest ourselves even for a moment.

Eventually they were spotted by some ‘respectable’ people who sent for a set of rescue apparatus, but this relied on getting a rope out to the rock, and attempts proved futile. The rescuers tried attaching ropes to ducks and setting them off across the waves, but only one duck made it, and the survivors couldn’t catch it. Next they tried using a howitzer to fire balls with ropes attached, but to no avail.

Then the chief coastguard’s brother, Edward Hull, had the idea of carrying a long rope round the bay so that it would stretch from one promontory to the other, with a second rope hanging down over the rock. The first attempt was late on Sunday afternoon and as darkness fell the rescuers almost left off, but in desperation two people grabbed the rope and shouted to be hauled in. According to the Baron:

…[the rescuers] immediately did so, upon which we heard a splash but could see nothing, it being at this time dark.

After this melancholy occurrence, the remaining survivors were abandoned to a second night without food, water or shelter. The next day, using the long rope and a basket, those on land were finally able to get the staples of life – wine, whiskey and bread – onto the rock. The Baron writes:

I cannot find words sufficiently strong to express how grateful the wine was to my parched lips. Each having partaken of this seasonable relief, we all huzza’d, and waved our hats and caps, in token of gratitude for what we had just had, and in the hope of being speedily relieved.

The equipment had a cot designed to transport human beings, and by this method the 14 survivors were removed, one by one. First was the only woman, Mary Leary, but Baron Spolasco managed to be second in line and was taken to a nearby house. One of the others subsequently died of exhaustion.

Only a month later he wrote his Narrative, and used it as a way of increasing his fame and spreading the word about his medical practice. He went through with his plan of going to Bristol and started up with the same wild claims about miraculous cures. But his adventures had only just begun.

In the next post, the intrepid Baron gets arrested for manslaughter, charged with forgery, and falls under the satirical eye of Walt Whitman in 1850s New York.

What an amazing tale! I look forward to the next instalment.