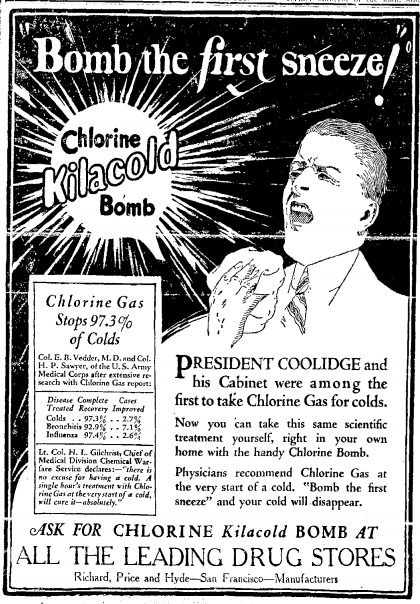

If you think a chlorine bomb sounds more like something from the battlefield than the medicine cabinet, then you’d be right about the origins of this 1920s remedy. The product, and a brief trend among physicians for treating colds with chlorine, arose from experiments made by the US Chemical Warfare Service after the First World War.

Thomas Faith, in his article ‘“As Is Proper in Republican Form of Government”: Selling Chemical Warfare to Americans in the 1920s’ (Federal History, 2010) places these experiments in the context of a public relations campaign to improve the CWS’s unsurprisingly poor image. The Service needed to contribute positively to life in peacetime, and what better way to appeal to the public than to announce a cure for the common cold?

While the influenza pandemic was claiming millions of lives, doctors at Edgewood Arsenal, Maryland, noticed that flu was less common among workers in the chlorine gas manufacturing plant than elsewhere. Intrigued by this anecdotal evidence, Lieutenant Colonel Edward B Vedder and Captain Harold P. Sawyer of the Army Medical Corps spent a year experimenting with chlorine gas on patients with ordinary colds. Reporting their findings in March 1925, Vedder revealed that of 440 cases, 261 were ‘cured’ and 149 were ‘improved’ by the treatment. Such an improvement might have been vague and unquantifiable, but the researchers also sent out questionnaires to physicians using the treatment. They got an overall favourable response, and took that as proof that it worked.

Finding a cold cure might be impressive enough, but Vedder and Sawyer had gone a step further and claimed to cure the cold of the President of the United States. In May 1924, Calvin Coolidge spent 45 minutes in a sealed chamber, breathing in a low concentration of chlorine gas. By the next day, his cold had become so bad that he had to cancel his official engagements, but after two more treatments he was well again. A cold getting better after three days? Who would have thought it?

In 1925 the University of Minnesota demonstrated via a controlled experiment that patients with colds recovered in the same amount of time with or without chlorine, but by then the idea had entered the commercial world and sufferers were being exhorted to ‘Bomb the first sneeze’ with Kilacold.

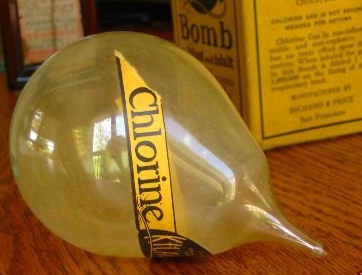

The Kilacold chlorine bomb was a teardrop-shaped glass ampoule containing 0.35g of chlorine gas. The patient had to break the end off to allow the gas to permeate the air of a closed room and, according to the advertising, their cold would disappear within an hour. The treatment was also promoted for flu, whooping cough, croup, bronchitis and for diphtheria carriers, but was not recommended for people with asthma. The bombs cost 29c each at Walgreens in 1925.

A few years later, 11 cartons of the bombs were seized at Portland, Oregon, and condemned as misbranded because the packaging stated that the contents were ‘Absolutely harmless’ and ‘positively not poisonous in any way to the human system.’

Although a 1927 Kilacold advert spoke of chlorine as an agent of death and destruction in war, it continued by using a rather tasteless statement to assure punters that the medical form was different.

‘Chlorine bombs are safe and sane,’ the advertising asserted. ‘Thousands of doctors declare the late war worthwhile because it gave the world the chlorine treatment.’

Wow. That’s something I have never heard before.

Very cool.