A box of confectionery arrived at the green room of the Princess’s Theatre, Oxford Street, on 6 November 1894 … with no well-wishes attached. The recipient was Anna Ruppert, whose new venture as a theatre manager and actress was a departure from a long career as a beauty specialist.

Anna Ruppert ate a considerable quantity of sweets that night. The next day, she fell ill, and although she struggled onto the stage that evening, she could not continue beyond the first act. The sweets had been laced with carbolic acid and, although the intended victim survived and offered a £100 reward, the perpetrator was never found.

Poison was a recurring theme for Anna Ruppert. Earlier that year, she had given an affidavit against the 1889 conviction of Florence Maybrick, who had allegedly extracted arsenic from flypapers in order to murder her husband. Ruppert testified to the common usage of arsenic as a beauty aid, pointing out that women tended to keep this practice secret from their male relatives so as to maintain the illusion of natural beauty. The all-male jury who convicted Maybrick would perhaps have found the defendant’s claims more believable had they only known what went on at the dressing table.

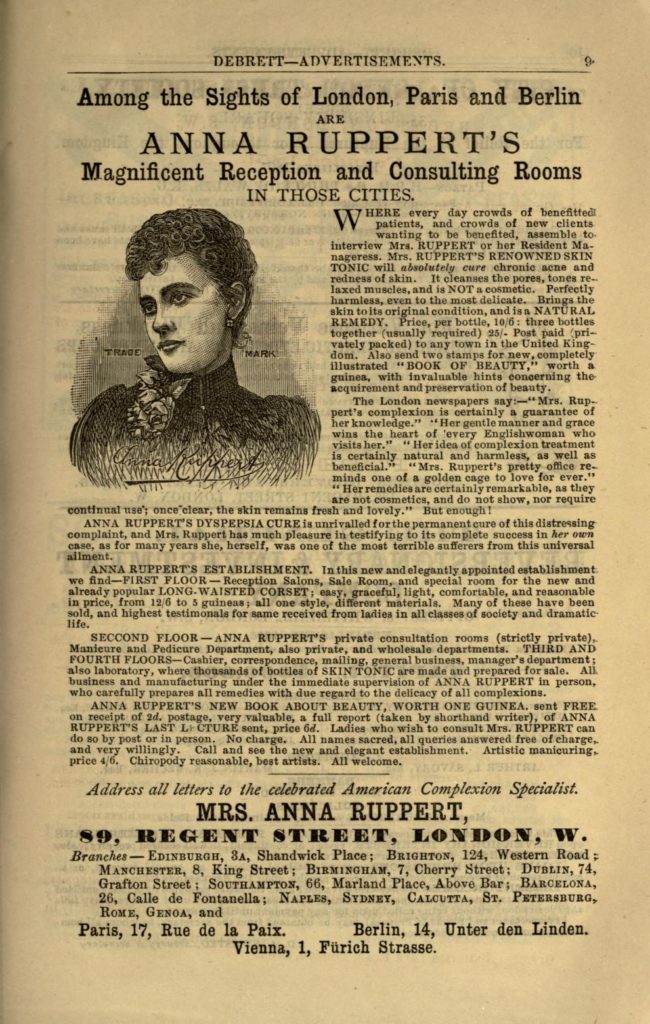

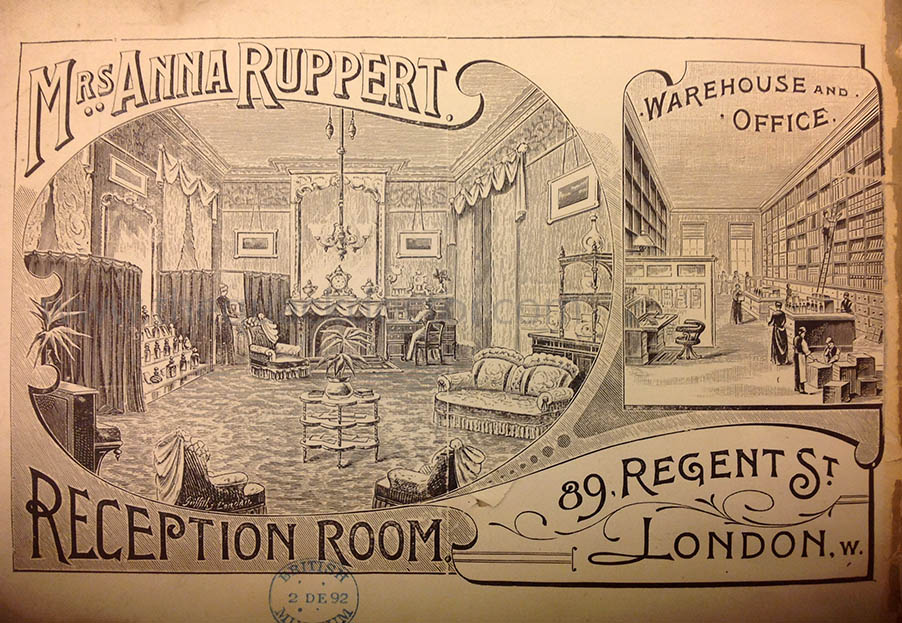

Ruppert’s knowledge had grown through her career as a complexion expert, or dermatologist. She operated from luxurious premises in Regent Street and comes across as an ambiguous character – admirable for her determination to succeed in a male-dominated business environment, yet selling products just as questionable as those of any male ‘quack’.

Ruppert was born Anna Shelton in 1864 in Pleasant Hill, Cass County, Missouri. In her teens, she sought help (either from an ‘old woman’ or from a St Louis druggist, according to different accounts) to get rid of a birthmark on her face. She then set out to share the curative formula with the rest of the world. She married Henry Ruppert in 1883 and they moved to New York, where her business as ‘Madame Ruppert’ took off.

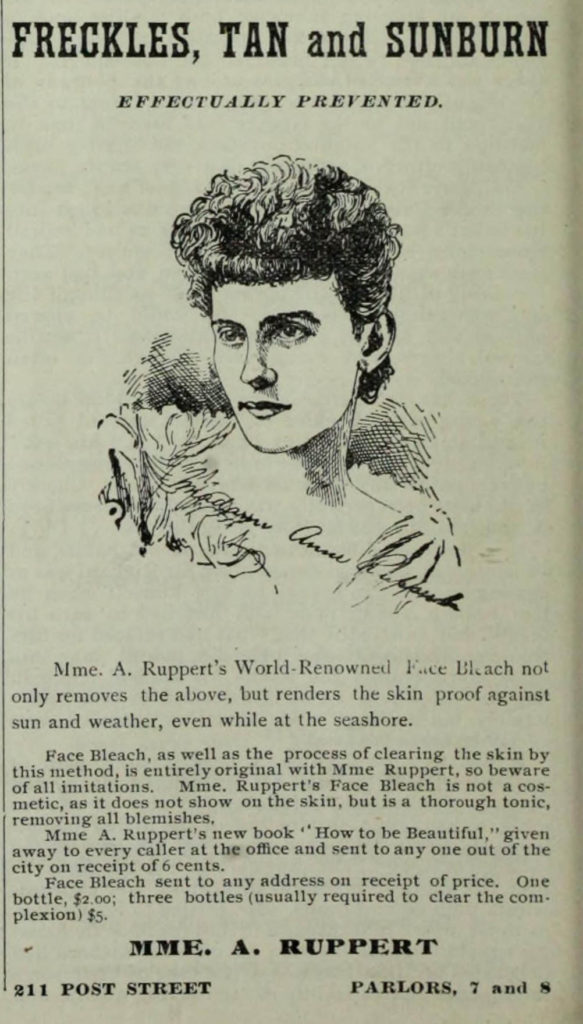

Newspaper advertisements for ‘Madame Ruppert’s Face Bleach’ offered consumers a way to remove freckles, tan, blackheads, eczema, acne and anything else making them fall short of the required aesthetic standard. Although Ruppert did not specifically target an African American market, her products were part of a context in which the pressure on black women to lighten their complexions led to a proliferation of whitening lotions, often containing harmful ingredients.

The Rupperts divorced in the late 1880s, with Henry Ruppert attempting to claim the rights to the Face Bleach and advertising for a while in competition with his ex-wife. Anna Ruppert later married an Englishman, Richard Armstrong, but retained her professional name. When the couple moved to London in 1891, face bleach had less overt racial connotations than in the American context, but was dubious in another way; it echoed the fraudulent activities of Madame Rachel Leverson, whose process of ‘enamelling’ the skin had scammed Londoners in the 1860s-70s. Perhaps to distance herself from the likes of Leverson, she used the name Mrs Ruppert rather than Madame in her British advertisements.

Ruppert rebranded the Face Bleach as Skin Tonic and set out to educate the British about enhancing their looks. Her public lectures, at which she would appear in fashionable gowns and floral garlands, attracted women and men alike.

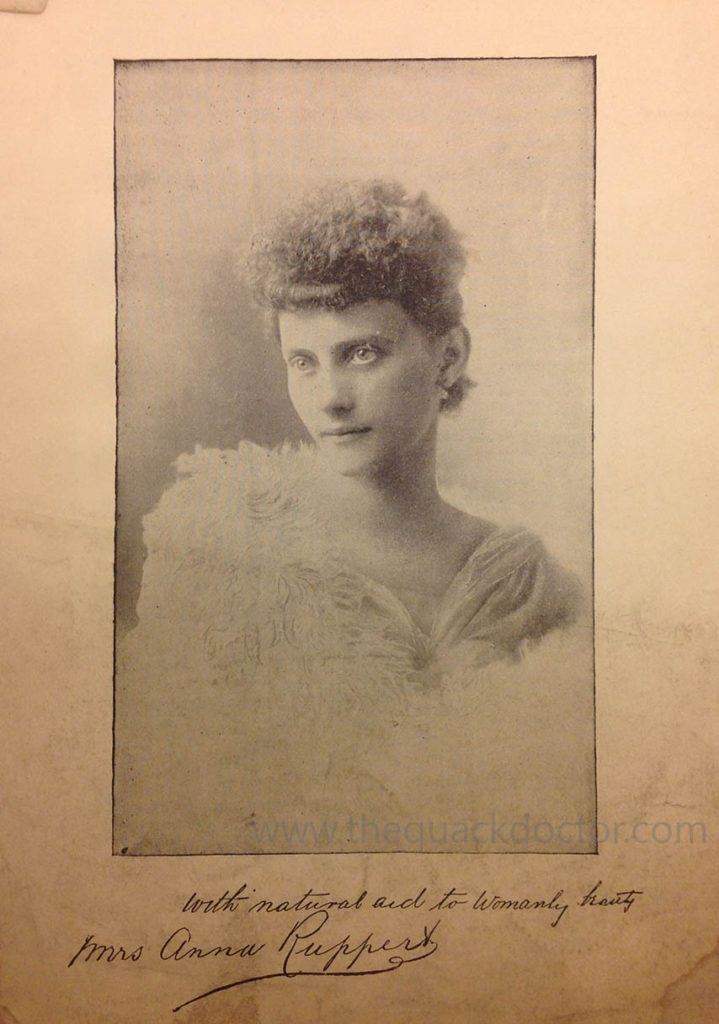

Ruppert’s marketing messages trod an equivocal line between the notion of ‘natural beauty’ and the need to buy products to create that beauty. Her lectures espoused her disapproval of make-up and advised that true beauty came from a pure heart. Yet her range included face powder to give the skin a velvety look, and ‘Mrs Anna Ruppert’s Red’ to impart vibrancy to the cheeks and lips. The contradiction between her advocacy of naturalness and her sale of skin-whitening products has obvious parallels with the beauty industry of today.

Ruppert became an ‘agony aunt’ for Hearth and Home magazine, dispensing beauty advice in a friendly manner that drew her a loyal following. In 1893, however, another writer took over her column. No explanation was given for Ruppert’s departure but anyone following the news would be able to guess – the British Medical Journal had revealed that her skin tonic contained corrosive sublimate (mercury (II) chloride) and had caused mercury poisoning in the case of a ‘Mrs K.’

Later that year, Ruppert was prosecuted in Dublin for infringing the Irish Pharmacy Act. The Chemist and Druggist reported the case and, unusually, sent a representative to get Ruppert’s side of the story. The interview, ‘A Fair Litigant’s Bower’, (20 January 1894) describes her plush Regent Street headquarters, and presents Ruppert as an astute, disingenuous character whose insistence that she was ignorant of Irish law is at odds with her clear intelligence and business acumen. Ruppert describes her eighteen-hour working days managing a business that dealt with more than 18,000 clients.

The Chemist and Druggist’s journalist was impressed. Clutching a photograph she had given him, he left with ‘the conviction that, whatever the merits of her lawsuits, the lady I had interviewed is as clever and

resourceful a woman as one is likely to find in a day’s journey.’

Published in the C&D on 20 January 1894.

After the prosecution, however, Ruppert’s reputation as a beauty consultant declined. During 1894 she turned to acting and theatre management, hiring the struggling Princess’s Theatre and taking the lead roles in her own productions. Her first outing as Odette was described as ‘amateurish’, but her company’s adaptation of the Australian novel, Robbery Under Arms, went down a little better; at any rate, Ruppert ‘looked pleasant and managed a beautiful white horse with much grace.’

Her health, however, was failing. A couple of months after the incident of the poisoned sweets, she returned to the US and tried to re-establish herself as a lecturer on dermatology, but became too ill to continue. She had tuberculosis, and died in her hometown of Pleasant Hill on 16 April 1896 at the age of 32.

The brand name continued into the early twentieth century under new management, still using Anna Ruppert’s portrait in the advertisements. Customers were not aware that the Madame Ruppert who promised to transform their looks had left her own beauty behind for ever.