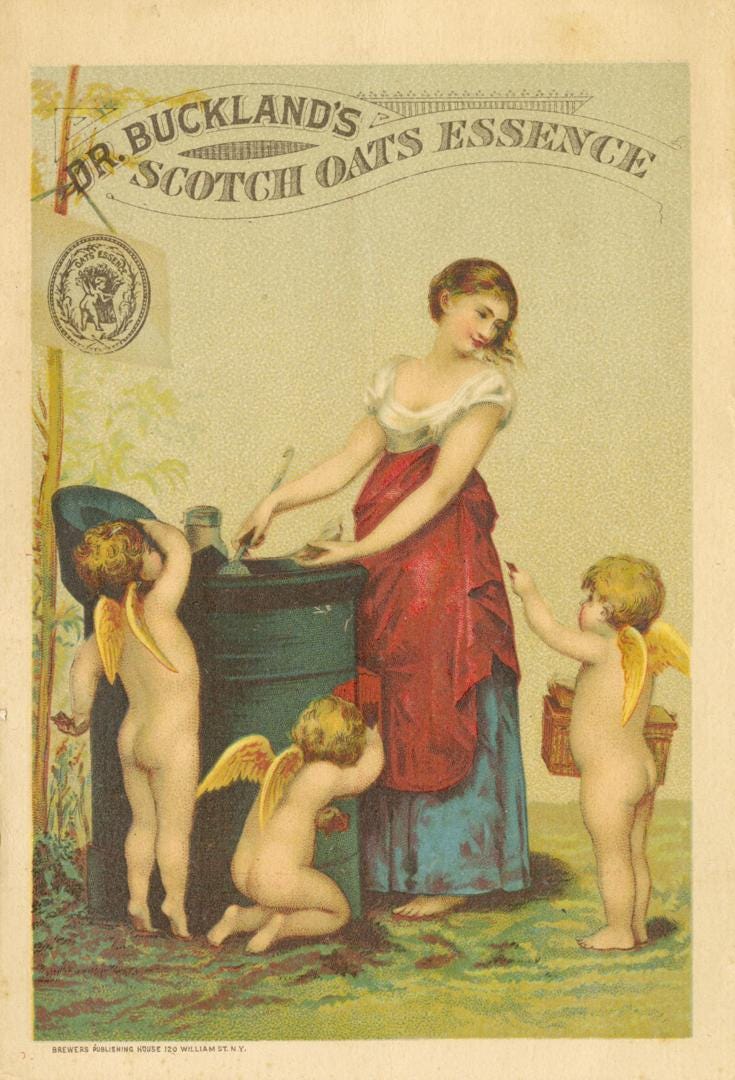

The name of Dr Buckland’s Scotch Oats Essence evokes wholesome scenes; a warming bowl of porridge perhaps, prescribed by a kindly Highland doctor to nourish a convalescing crofter while the snow swirls across the mountains.

This American patent medicine, however, did not have much of the wholesome – or the Scottish – about it. Its short reign of advertising prominence ended when analysis showed it to be a dangerous and cruel fraud.

The Scotch Oats Essence was introduced in the 1880s by Dr Henry (Harry) Hubbell Kane (1854-1906). A genuine graduate of Long Island College Hospital, he had started out in regular practice and authored several medical works, including The Sick Room (1879), The Hypodermic Injection of Morphia (1880) and Drugs that Enslave (1881). He married Mattie Butts of Cincinnati in 1876, but the union would not last.Subscribed

In 1883, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine published his first-person account of visiting a drugs den. A Hashish House in New York: the Curious Adventures of an Individual who Indulged in a Few Pipefuls of the Narcotic Hemp narrated in melodramatic – and probably fictional – style the author’s hallucinations of dragons, serpents and jewels.

For a couple of years, Kane ran an addiction treatment sanatorium called the De Quincey Home (named after English opium-eater Thomas De Quincey) in Fort Washington; when that closed, he offered a mail-order home treatment ‘whereby anyone can cure himself quickly and painlessly.’1

The patent medicine trade proved more profitable than general practice or writing, and in 1886 Kane launched Dr Buckland’s Scotch Oats Essence, based at 174 Fulton Street, NYC.

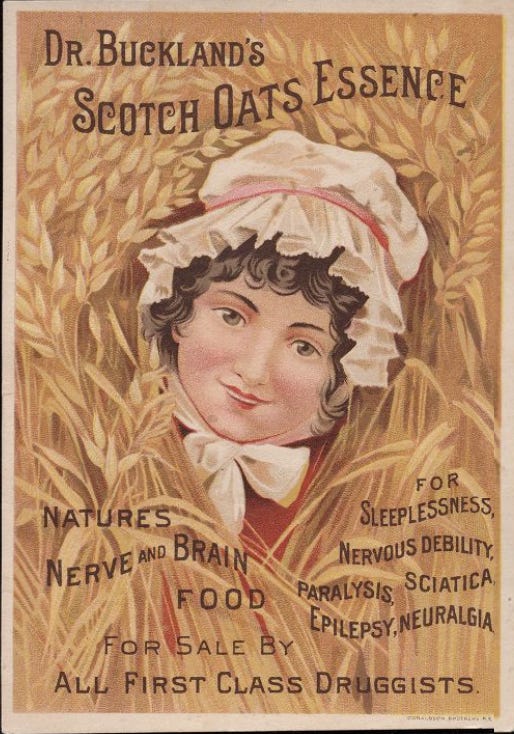

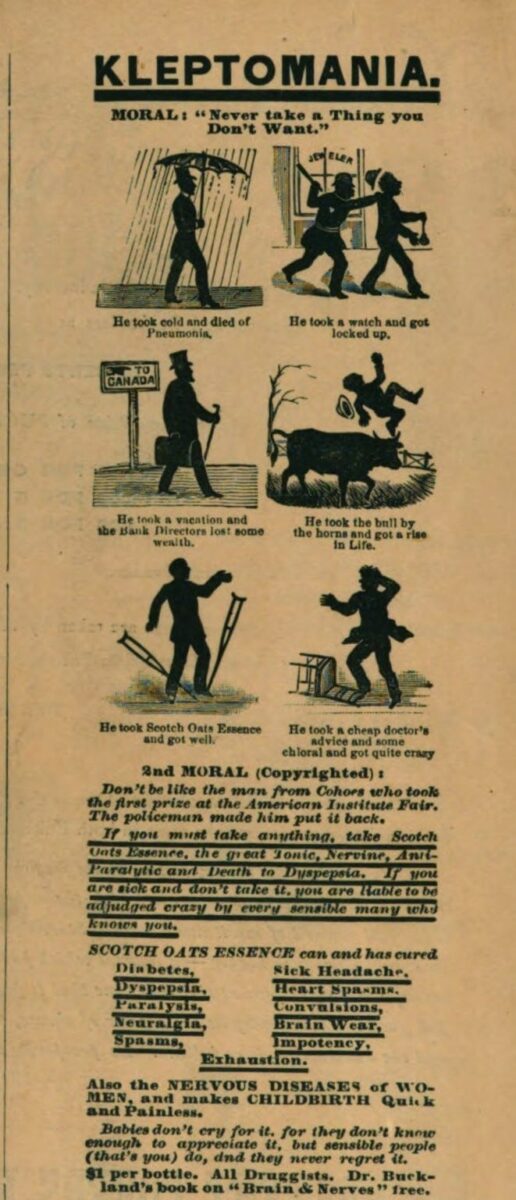

Early ads pitched the medicine as a cure for insomnia, alongside a list of disorders related to the nervous system – sciatica, headaches, neurasthenia, hysteria, ovarian neuralgia, epilepsy and more. The product, so the ads claimed, would also cure drunkenness and opium addiction – conditions of particular interest to Kane.

The copy pointed to the unsustainable pace of modern American life as the cause of nervous exhaustion:

We eat too fast, we think, work, love, walk, run, sleep, push, dance and dissipate all too fast. It is veritably the dance of death, and it is a whirlpool of destruction that sucks down into its vortex thousands of men who might have lived a good thirty or forty years longer.2

The Scotch Oats Essence would save those teetering on the brink of this vortex and keep them happy and healthy – and out of the mad-house – until a grand old age.

In 1887, tragedy overtook Harry and Mattie Kane. Their 8-year-old son Percy died of capillary bronchitis and it appears that they began living separate lives. More difficulties came along in April 1888, when the Druggists’ Circular and Chemical Gazette published a damning chemical analysis showing that the Scotch Oats Essence was by no means a safe cure for addiction.

Kane called his medicine’s active ingredient avenesca (after the oat genus Avena). This essence was supposed to tone up the little grey cells of the brain and nervous system, while another component called boskine would keep the bowels regular and prevent the liver getting clogged up. Analyst Dr R G Eccles found that more than a third of the Essence comprised alcohol and there was an estimated two grains (129.6mg) of morphine per bottle.3 Addicts no doubt did feel temporarily better when they took it, because it satisfied their cravings.

In the following issue, the Circular kept going with its exposure of what it called ‘one of the most bare-faced and rascally tricks to deceive and injure the people.’ They set out to find Dr Samuel A Buckland, the supposed inventor of ‘so devilish a plan to sacrifice the innocent by making them slaves to the opium habit.’4

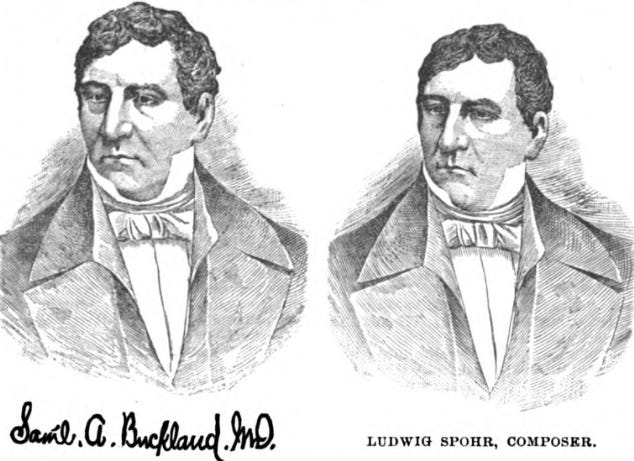

Dr Buckland, it transpired, was a fictional character. Kane’s promotional materials claimed that the doctor was born in Milford, Connecticut in 1804, graduated from medical college at the age of 26 and devoted his life to studying diseases of the brain and nervous system, while also working as a country physician. He discovered the Scotch Oats Essence in 1854 and cured himself of paralysis. A representative of the Druggists’ Circular went to Milford and found that no one there had ever heard of Dr Buckland. The old timers couldn’t recall any family of that name, and a 90-year-old local doctor had practised there since 1821 without encountering this ‘great benefactor of the human race.’

The Circular also showed that the portrait of ‘Dr Buckland’ on the advertising pamphlets was actually that of German composer Ludwig Spohr (1784-1859). Newspapers picked up on the story and publicised the findings, warning customers that the Essence could start or maintain an opiate addiction.

Another medical journal, The Western Druggist, did not hold back in condemning the product, saying:

A more diabolical concoction could hardly be devised; the crime is not merely obtaining money under false pretences, nor simply a case of ingenious and wholesale robbery, but a devilish scheme for undermining the mind, soul and life of its victims, and this under the pious pretence of strengthening the body and restoring the jaded mind. 5

Faced with this criticism, Harry Kane went on the attack. He placed advertisements condemning the ‘Cowardly attempt at assassination,’ and accused a ‘certain clique’ of trying to destroy his medicine’s reputation because it kept people out of the profit-making lunatic asylums and inebriate homes. Kane explained the results of Eccles’ analysis by claiming that someone had stealthily injected morphine through the corks in the bottles. He published his own analysis by ‘Consulting Chemist’ Dr Willard H Morse, who certified that it did not contain morphine or any other opiate. (Morse got arrested a few years later for running a ‘cash for analysis’ racket where he would charge patent medicine manufacturers for saying whatever they wanted him to say.)

Kane appears to have used his wife’s money to fund the business and, now that the Essence’s reputation had nosedived, she wanted it back. In December 1888 the New York City Sheriff wound up the company and sold off its stock, with judgments totalling $39,610 made in favour of Mattie Kane.6

The fame of Dr Buckland’s Scotch Oats Essence might only have lasted a few years, but Dr Kane didn’t give up on his medical business ambitions. His next scheme offered treatment for men suffering prostate problems, nervous debility and ‘feebleness’. Find out more in my Substack article here.

1 Advertisement, The Port Chester Journal, 25 September 1884.

2 The Boston Globe, 6 November 1887.

3 R G Eccles MD, ‘Scotch Oats Essence’ The Druggists’ Circular and Chemical Gazette, April 1888

4 ‘Is Dr Sam’l A Buckland the discoverer of Scotch Oats Essence?’ The Druggists’ Circular and Chemical Gazette, May 1888.

5 The Western Druggist, May 1888.

6 The Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester), 2 December 1888.