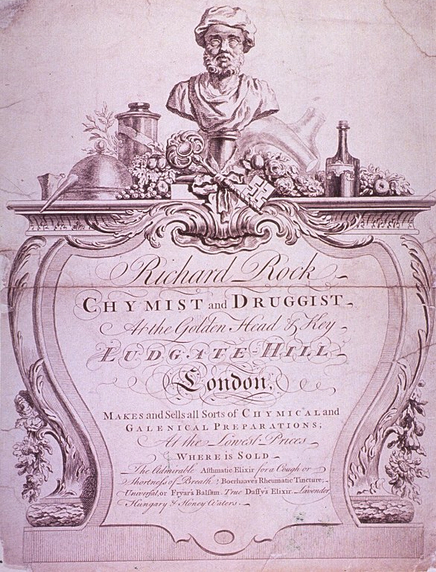

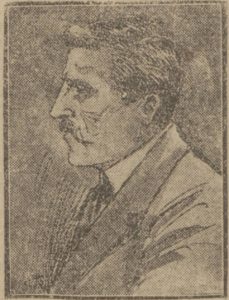

This is a short excerpt from a speech attributed to Dr Richard Rock in a satirical mid-18th-century pamphlet called The harangues, or speeches, of several celebrated quack-doctors, in town and country. Rock, whose Viper Drops have previously appeared on this site, is sometimes referred to as an itinerant quack, but his activities were rooted in his premises at Ludgate Hill. When he went out to promote his products mountebank-style, he remained close to home, becoming a familiar figure in Covent Garden. The image of him on the left is a detail from plate 5 of Hogarth’s The Harlot’s Progress.

The first edition of Harangues is undated but the exchange with the Basket-woman puts the speech at 1742/43, when gin consumption was at its height and civil disturbance was in the air. Rioters protested against proposals that would repeal the largely ignored prohibition and bring gin consumption under the control of the law i.e. make it profitable for the government.

***************************************

Gentlemen,

It is with great Pleasure that I see you all, as soon as I arrive in my Chair, flock round about it: It is a Proof, that as I come to do Publick Good, I have a Publick Esteem. I don’t know, Gentlemen, whether here, in Covent-Garden-Market, ye ever heard of Public Spirit; but there is such a thing talk’d of among Parliament Men.

Basket-Woman. Oh! That is the new Act of Parliament, Doctor, about Spirituous Liquors. Pray, Doctor, will Gin be cheaper, or dearer?

Doctor. Cheaper, cheaper, or at least as cheap, my Dear; you may thank Goody Sandsby for that.—But without Jest; —The Public Spirit I meant was, what we in the City call a Love for our Country, without any private View: They talk of the same Thing at Westminster. It is this Publick Spirit, which brings me here among ye: It is the Good of my Country, which engages me to enter into its Public Service. I come not to impose upon ye; for they, who impose on the People, whether it be in Physic or Politics, are equally Quacks.

Some Fools have indeed, call’d Me a Quack: But what is a Quack? A Cheat. —Now, ye all know, I have dispens’d my Medicines, I have effected Cures, I have attended ye all, in this very Place for several Years, and no one ill Thing has been laid to my Charge. ——Let any other Great Man at Court say as much if he can. —I am always the same be I where I will: When I am at Leicester-House I am the same Man as when here; or if at St. J——s’s, my Packets are the same, my Advice is the same and my Speeches to ye are all to the same Purpose.

Had I any private View, any Ambition, any Desire, but to serve my Country, I could have gratify’d them. I am above such paltry Things, as foolish Dignities, and empty Titles. Let P——rl——t Men accept Places, and desert their Cause; let Commoners do pitiful Actions to become L——ds: But let Dr. ROCK be still Dr. ROCK.

.

.

Why are the references to Parliament, the Lords and St James blanked out as if swearwords?

It was quite a fashionable literary device at the time, usually for people’s names, but also for places. I think it’s meant to pretend that the author is being so edgy that he could get into legal trouble if he spells out what he means. As in this example, however, the names were nearly always identifiable anyway, so it’s more that it was the ‘in thing’ rather than there being any genuine legal threat. The author above isn’t even consistent – he mentions Parliament men in full near the beginning!