David and Esther von Cavania practised as doctors in the 1870s, selling a remedy called the Wonder-Worker Lotion. Roger Cavania Sanders tells us more about his great aunt, Mademoiselle Cavania.

Esther Jane Neumane was born in 1843. Her father was David Brown von Cavania, who was convicted at Leeds Magistrates’ Court in 1876 effectively of being a ‘quack’ doctor.

The first mention of Esther’s profession is in an advertisement in the Leeds Times in 1861 where she is referred to as Mademoiselle Cavania, alongside her father, ‘Professor Cavania’. Both claimed to be members of the Eclectic Reformed College.

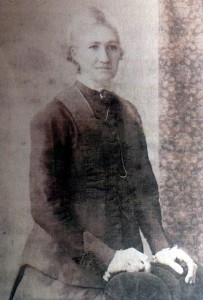

By 1865, in the Manchester Times, Esther has become ‘Madame Cavania Newmane’ (note the difference in spelling from her actual married name), who is ‘Professor of Medicine for Diseases of Women and Children’ and ‘Member of the Eclectic Reformed College of Physicians, New York, U.S., America.’ The advert also states: ‘Diploma granted 12th day of January 1860.’ Note that Esther was born in April 1843, so the diploma was granted when she was still aged 16! It is known that in England some degrees were granted to the self-taught and tutored, and doubtless Esther would have received help from her father, but this seems ridiculously young. This advertisement, like most others, continues with outlandish claims for cures of cancers, tumours, consumption, scrofula, etc.

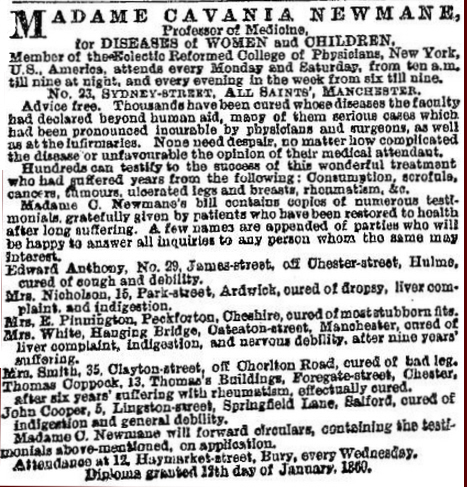

By September 1865, Esther is claiming to be ‘New Doctress by Diploma’, also in the Manchester Times. Further, in the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent, her advertisement states ‘Mademoiselle Cavania, the only female Doctor, who has stretched forth her hands for the good of her fellow creatures’. The woman must have been a saint!

The Eclectic Reformed College in New York certainly did exist and was accepting women in 1860. The Eclectic movement itself was a sincere one that tried to treat the person as a whole and to use traditional remedies and homeopathy to effect cures.

At one time there were 20,000 eclectic medical practitioners in America, but they faced increasingly strong opposition from more conventional practitioners and were eventually pushed to the margins.

This pattern was repeated in England and Esther’s father was subject to a police ‘sting’ operation to bring him to the court in Leeds in 1876, where his American diplomas were discounted. Esther was referred to at the trial but not herself charged.

Esther and her father jointly ran a patent medicine business, offering ‘Cavania’s Abyssinian Liver and Nervine Pills’ and other lotions, examples of which are in the museum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society in London. The borough analyst at the Leeds trial confirmed that they contained nothing that could harm anyone. Esther continued to advertise the products for many years after her father’s death in 1886.

Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman to receive an MD from an American medical school, was already listed on the GMC’s Medical Register by the time Esther began practising, but was not permanently based in the UK. Elizabeth Garrett, too, became qualified to practise medicine in England as a licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries. (Interestingly, Garrett took her examination on 28 September 1865 – the very date of one of the adverts pictured above!) It would be another five years, however, before a medical degree was awarded to a British woman on this side of the Atlantic, when Frances Hoggan qualified at the University of Zurich in 1870.

Whether Esther Jane’s claim to qualification is valid can be argued either way. The Eclectic Reformed College admitted women students from 1850 onwards and was part of a respectable, if perhaps ill-informed, movement in medical knowledge. Esther is very specific about the date of her diploma and advertises its existence in a widely read newspaper.

However, some 26 years later a court refused to accept the validity of her father’s similar American diploma, and one has to have serious doubts about a sixteen-year-old receiving such an award, however achieved, even in America, and even with considerable help from her ‘qualified’ father. The outlandish claims for cures made in advertisements only increase one’s doubts.

Sadly her effects, including any diploma, were not handed down within the family so we shall never know whether the diploma really existed.

David Brown (von Cavania) was my great grandfather, and Esther therefore my great aunt.

Roger Cavania Sanders

private health insurance policy is taken for the individuals or family.

This is awesome! I’ve read about how the midwives were being displaced by male doctors because of their idea of “profession” verses “quackery” But this is wonderful because this meant that she went from the “lower” to the “accepted” even if her diploma has never found, and also even though there were questionable practices. “Professional” Men did the same.

Enjoyed article very much, how can I get in touch with Rodger Cavania Sanders?I have information on Esther’s daughter

Thank you – I will pass your message on to Roger. Are you happy for me to let him have your email address?

Yes, that would be fine