When you’re under the weather and you Google your symptoms in an attempt to convince yourself that you are about to die, spare a thought for Jean Landess, whose perusal of Chambers’s Encyclopaedia was the beginning of a tragic chain of events.

In May 1868, 39-year-old Mrs Landess, of Paisley, had just weaned her youngest child and had developed what she called a ‘weed’ in her breast. She sought medical help, and the family doctor poulticed and lanced two small abscesses.

Mrs Landess, however, discovered from the Encyclopaedia that her symptoms were almost exactly like those of breast cancer. On the recommendation of an acquaintance who had apparently been cured, she decided to consult an unlicensed practitioner by the name of Paterson. This might seem like a naïve or even downright stupid decision, but I think it’s understandable. She had recently undergone a painful invasive procedure, she was in the midst of the hormonal upheaval of stopping breast-feeding, and now feared that a terminal disease was going to deprive her 8 children of their mother. The recommended cancer-healer must have seemed a potential life-saver. Unfortunately, he proved quite the opposite.

Alexander Paterson was a shoemaker with a sideline in treating cancer patients. He made no claims to being a doctor and does not appear to have been out to swindle anyone. He was no less dangerous, however, for being well-intentioned.

Paterson told Mrs Landess that she did have cancer, but not to worry – it could easily be removed. The first stage of the treatment was a fly-blister (a plaster of cantharides) that would take off the surface of the skin, leaving it ready to absorb his cancer-curing salve. After the plaster had been on for about 12 hours, he applied the ointment and instructed the patient to renew it every day.

By Paterson’s next visit, most of the tissue had turned black, but he saw this as a good thing and reassured Mrs Landess that the treatment was going well. She, however, was suffering from headaches, vomiting and great thirst, and the inflammation of the breast began to spread into her arm. Two days later, she had a fit. Her husband described her appearance as:

…being like a ‘half-felled cow’. Foam issued from her mouth, and she roared most unnaturally.

That evening, she died.

Douglas Maclagan, Professor of Medical Jurisprudence at Edinburgh University, carried out a post-mortem examination and confirmed that Mrs Landess had never had breast cancer. There were traces of arsenic in her organs, and when he analysed Paterson’s salve he discovered that it was 49% arsenic and 51% lard.

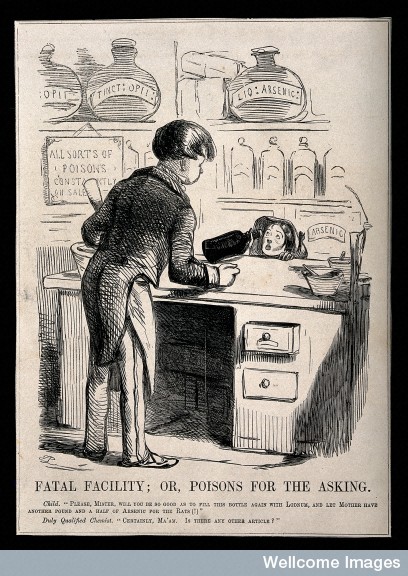

Arsenic salves were a long-established quack treatment for cancer, and local unqualified healers like Paterson were not unusual – though perhaps less common by the 1860s than they had been in the 18th and early 19th centuries. When Paterson was brought to trial charged with culpable homicide, the question was not whether he should have been practising as a healer in the first place, but whether he had been negligent when administering a dangerous medicine.

Paterson’s defence was that he had 20 years’ experience of treating cancer and that when Mrs Landess asked him for help, she knew very well that he was an unlicensed practitioner. Several witnesses came forward to say that he had cured them.

The judge, Lord Ardmillan, must have been in a particularly good mood that day. In summing up, he advised the jury not be too swayed by the fact that Paterson was unqualified, but to take into account his experience, the apparent cures of the witnesses, and the fact that any medical man could muck up sometimes.

‘A mere mistake,’ he said, ‘did not imply culpability.’

The jury found Paterson guilty. Lord Ardmillan, however, told him that ‘no one could suppose he meant any harm to the unfortunate woman Landess’ and sent him to prison for just four months.

.

.

God how horrific! It isn’t just the internet that can convince you that your demise is imminent. It is surprising anyone survived. These blogs are fascinating, but frankly worse than a horror story. I love them!

Thanks Suzie! I occasionally find things that are too horrendous even for this site!