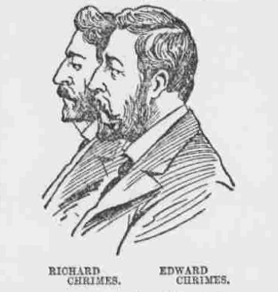

In 1890s London, the ‘Lady Montrose Pills’ blackmail scheme efficiently and heartlessly targeted more than 8,000 victims. In this comprehensive account of the case, Dick Weindling introduces the Chrimes brothers, who manufactured this audacious scam.

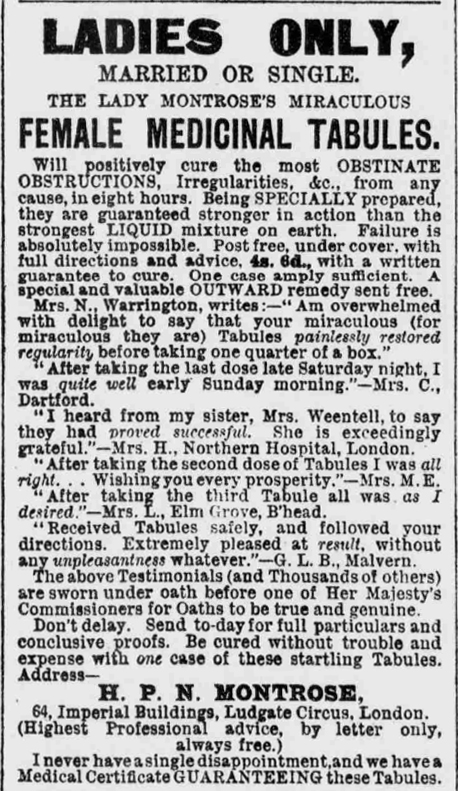

In April 1896 adverts began to appear in newspapers across the country. Addressed to ‘Ladies Only’, the advertisement promoted ‘Lady Montrose’s Miraculous Female Medicinal Tabules’, which would positively cure the most ‘Obstinate Obstructions’. People who read the advert knew it referred to abortions, which were illegal at the time. By sending 4s 6d (today worth about £24), ladies would receive the box of tabules (tablets), as well as a written guarantee to cure. They were assured that ‘failure is absolutely impossible’, and the advert included testimonials from satisfied customers. The advert was successful, and over the next two years about 12,000 women sent postal orders for the pills to 64 Imperial Buildings, Ludgate Circus. The men behind the advert were the Chrimes brothers, Richard, Edward and Leonard, but they all used aliases. The pills had no effect and did not remove the obstruction. The Chrimes brothers had carefully worked out the scam, and the women were even sent a second letter from another address (7 Pleydell Street, near Fleet Street), for Panolia Electric Blue Pills at either 3s 6d, 11s or 22 shillings for a box of extra strength. This used ‘knocking copy’ and said that Lady Montrose’s Tabules and any other advertised product, was not as effective as the Panolia Pills. These were so powerful they could not be advertised for fear of prosecution, and were only known by ladies telling other ladies.

The blackmail scheme

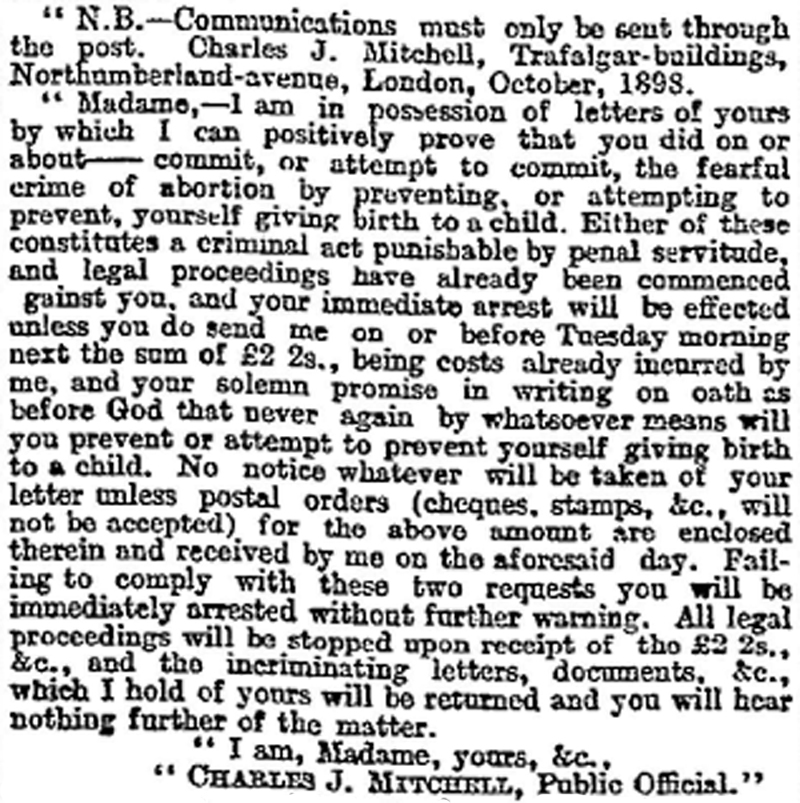

After about two years an even more devious idea was developed. In September 1898 the brothers had the names and addresses of thousands of women and they realised they could make a large amount of money by sending them a letter threatening to expose the women for attempting the criminal act of abortion. Unless the women sent two guineas to Trafalgar Buildings in Northumberland Avenue, they would immediately be arrested.

The scale of the blackmail was astonishing and required meticulous planning. On 14 September they advertised for a junior clerk and appointed young Norman Gibson, who lived with his parents at ‘The Briars’, Forest Gate. He started work on 26 September at a salary of 18s a week. A printing company was sent an order to make the circulars so that they did not contain any handwriting. Then another specialist company was sent 8,000 names and addresses to produce the addressed envelopes, and a large amount of stamps were bought from the Ludgate Circus post office. On 12 September they had purchased a Gestetner cyclostyle machine (an early duplicating machine), for £4 16s to make the circulars on the printed letters. The huge mailing went out on 7 October 1898 and the letters arrived the next day.

One was addressed to Mrs Kate Clifford at 18 King Street, Snow Hill. Her husband, who was a warehouseman, opened the letter and was shocked at what he read. He immediately took it to the nearby City Police station at Snow Hill. Detective Inspector Waldock read the letter and soon began to receive other similar complaints. Realising the large number of letters involved, he contacted Detective Inspector Richards at Scotland Yard and Detective Inspector Davison of the City Police. Davidson and his men made enquires at the various addresses to discover who had set up the blackmail plot. They discovered that three men carried on business at 64 Imperial Buildings as advertising agents in the name of Montrose. The men did not spend much time at the office, and the address was chosen because it had a particularly large letterbox. The mail was collected and taken to another address at Ludgate Hill. When the police went to 73 Ludgate Hill, they found that the same three men had worked there under the name of R. Randall and Co. since renting the office in August 1897. The office was empty but they found large amounts of pills and medicines, and also correspondence addressed to Montrose at the Imperial Building, and Panolia at Pleydell Street. All the addresses were put under observation, and on 10 October the police saw Norman Gibson go into Trafalgar Buildings to collect the mail which he was wrapping into bundles. A total of 475 letters were found containing £240. Gibson cooperated fully and said he had been hired just a few weeks ago and was told to take the letters in canvas bags to Brighton. On 8 October he had met Leonard Chrimes, who he knew as Charles J. Mitchell, at 3.00 pm on the arrival platform at Brighton Station. The police followed Gibson on his second trip to Brighton, but the Chrimes brothers must have seen them at Trafalgar Buildings and Leonard did not turn up for the meeting.

All three brothers had gone into hiding and warrants were issued for their arrest on 10 October. Detective Inspector John Davidson of the City Police was in charge of the case. After considerable effort, he arrested Richard and Edward Chrimes on 10 November and Leonard ten days later.

The Old Bailey trial

Richard Chrimes (32) alias Randall, Edward (31) alias Knowles, and Leonard (22) alias Mitchell, were charged under Section 46 of the Larceny Act with threatening persons with a view to extorting money. This carried a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. They were also charged with attempting the miscarriage of a female by a drug or poison, which was also punishable with life imprisonment. Their trial at the Old Bailey began on 16 December 1898. The Old Bailey printed and online versions record the trial but unusually say, ‘The particulars of this case are unfit for publication’. However, the high profile case was fully covered in the Times and most other newspapers.

Opening the case for the prosecution, Mr Mathews called it, ‘a plot of the most consummate infamy that was ever conceived by any swindler in the annals of crime’. He said that in the weeks following the threatening letter almost 3,000 replies had been sent to Trafalgar Buildings, with remittances totalled over £1,100. The GPO had returned the money to the senders of the intercepted letters. He believed that this would not have been a single mailing and that if they had not been caught, the Chrimes brothers would have sent out more letters demanding money.

Another swindle

In addition to the female remedies, under the alias of the ‘Bradbury Brothers’, they had sold cosmetic soap for the hair, oddly called ‘Hare’s Soap’. They offered a two guinea prize to people who could fill in the missing words in the advert. This was a well-known con. The Star newspaper ran an article on the brothers on 28 September 1898 saying it was a swindle as they did not give out prize money. Because the other charges were so serious, the prosecution counsel said the Chrimes brothers would not be charged for this offence.

Various witnesses were called who could identify each of the brothers, the numerous aliases they had used, and the many offices they had rented in the City to conceal the blackmail plot and their scams. However, they made a mistake when renting two of their offices by giving their father Joseph Chrimes as a reference, thus leaving a paper trail which connected the name Chrimes with some of their aliases.

Robert Berrill was the laboratory manager of the well-respected company ‘Stephen Wand’ at Haymarket in Leicester, which had been making pills and medicines since 1864. He said the blue and pink coated pills and tabules both contained reduced iron, extract of nux vomica (from the seeds of the tree of the same name which contained small amounts of strychnine), sulphate of quinine and extract of gentian. From October 1897 to June 1898 Ward had supplied goods to R. Randall which totalled £105. He said the tabules would not have the effect stated in the advert but would be a good blood tonic. Ward had previously supplied the same prescription of medicines to Abbot and Co. of St Andrew’s Hill City, which he understood, Edward Chrimes had taken over.

Richard Chrimes and his family had been living in Bramah Road Brixton until he went on the run. In court Thomas Wade said he had advertised a grocer’s shop at 167 Maple Road, Penge for sale on 12 October. Richard Chrimes under the name of Richard Randall, called on him and bought the business for his wife for £46. Using the information they had collected, Detective Inspector Davidson put the shop under observation from 17 October when Chrimes took possession. They saw Richard serving behind the counter dressed in a grocer’s cap and apron. However, they did not have sufficient information to prove he was their wanted man.

Arrested during dinner

By chance, Florence Gale, the housekeeper at two of the offices, was the wife of PC Gale of the City Police. As he knew all the brothers by sight when they had used their aliases to rent the offices, he was asked to keep watch on the shop for three weeks. On 10 November Inspector Davidson had enough evidence, and with PC Gale arrested Richard and Edward while they were having dinner at the grocer’s shop. During a search of a bedroom above the shop, they found papers which gave them information about Leonard. He was traced to Plymouth and then to Mulvra Farm near St Astell in Cornwall, where he was attempting to become a chicken farmer under the alias of Harrington. On 20 November he was arrested at 7.30 am, while he was still in bed.

Initially all three brothers pleaded Not Guilty, but at the Old Bailey Edward and Leonard changed their plea to Guilty, and the case proceeded against Richard Chrimes.

Mrs Kate Clifford gave evidence and said she had purchased the Lady Montrose tabules in October 1897, but they did no good and she subsequently had a baby. Her husband William had taken the threatening letter to the police, which was the first they knew about the blackmail.

Henry Baldwin, a clerk in the letter addressing firm, G.S. Smith of Bevis Marks, said he saw Edward and Leonard Chrimes who gave him 42 books containing the 8,000 names and addresses they had collected, and asked him to produce the printed envelopes. Frederick White, an advertising agent, had received the adverts from the Chrimes brothers whom he knew well. He said the advert for the female products cost five times more than the standard newspaper adverts of the same size. He had been paid a total of £2,000 to place their adverts since April 1896. He said he also placed ads for two rival female remedy companies.

Mrs Margaret Chrimes gave evidence, and said that her husband Richard had been on holiday in Sidmouth with her and the children from 24 August to 17 September. So he could not have rented the office at Imperial Buildings at the time stated. Richard then gave evidence, which he was allowed to do in his own defence under a new Act. He had previously been a canvas bag maker and then he had been employed as a clerk by a City firm. In 1897 he began working for his brother Edward who had started as an advertising agent at 73 Ludgate Hill. He admitted that he collected the letters addressed to Montrose and that he had ordering the medicines from Ward Chemists in Leicester. When questioned he said the Lady Montrose tabules were not for procuring an abortion but simply to cure obstructions. He claimed he only became aware of the threatening letter on 8 October when a soldier called at Imperial Buildings and showed it to him. He said he bought the grocery shop in Penge when Edward was no longer able to employ him, and because his wife had previously been in the grocery trade. Edward had employed him at £3 a week, but later had become ill. So on 5 November he had collected Edward from Clacton and brought him to live above the grocer’s shop.

‘Not a very nice business’

When Judge Hawkins asked why he and his brothers did not use their own names, Richard replied, because the ladies products were not a very nice business. The judge said it was a horrible business. Richard responded and said he did not see any great harm with it. The recipes for the tabules were taken from the ‘Household Physician’ and were harmless: in fact they had to show the certificate to newspapers before they were allowed to advertise. His barrister said Richard had simply worked for his brother Edward, selling Lady Montrose tabules and had no knowledge of the threatening letter.

The next day Judge Hawkins summed up the case. He said the charge was one of the most serious known to the criminal law because it affected the happiness, comfort and safety of every man or woman. The sentence for sending such a letter was not less than seven years and a maximum of life imprisonment. No one could doubt the wording of the Lady Montrose advertisement meant it was for abortion. The manufacturing chemist in Leicester said it was harmless, a very good blood tonic, and would not have the slightest effect on a woman in the state of pregnancy. After nearly an hour the jury returned with the verdict of guilty. The foreman asked that steps should be taken to stop adverts of this kind appearing in the press. The Judge said he would pass the request to the Home Secretary.

The defence barrister for Leonard pointed out the ten-year difference in age between him and his two older brothers who had obviously been an evil influence on him. Edward’s barrister said he had been employed as a book keeper in several firms but afterwards he had attempted to float a magazine. He had gone into partnership with an unnamed man who he thought was a dramatic agent. Afterwards he found out this was not true, but he had joined him in a partnership selling female remedies (this was Abbott and Co). The partnership was later dissolved. When Edward still failed to establish his magazine, he continued the medical business and asked his brothers to join him. He took the whole responsibility for the blackmail scheme and said that Richard and Leonard had nothing to do with it.

‘I did not know I was doing wrong’

After listening to the defence counsels, the Judge said all three men had preyed on women, and he read out several letters which showed how terrified the victims were with the threat of immediate arrest. He read the following as a typical letter:

Dear Sir,- I am very sorry to have done wrong. I did not know I had done wrong to myself or to any one else, and, as regards trying to prevent myself from being confined, I do not know that ever I have done so, for the child that you are alluding to is a big fine girl as healthy as any child could be, and is eight months old; and I do not call that doing away with the baby, or trying to do so. But if I have done wrong I ask you to forgive me, as I did not know I was doing wrong. I will promise that I will never do wrong any more, for Christ’s sake. Amen.

On 20 December Edward and Richard were sentenced to 12 years imprisonment and Leonard, because of his younger age, to seven years. They were sent to Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight. In April 1899 Richard’s sentence was reduced to five years following his appeal to the Home Secretary.

Life after prison

After serving their sentences, Richard returned to his wife and ran a laundry business in Portslade near Brighton and Hove, and later became an hotelier. He died in 1955 in Holborn. Edward became a publisher, so perhaps finally managed to get his magazine off the ground. He changed his name to Edward Belgrave, and in 1931 married a woman who was 20 years his junior. In 1939 he was living in Hove and he died in Hastings in 1952. Leonard seems to have changed his name and disappeared without trace.

Dick Weindling is a historian who, with co-author Marianne Colloms, has published numerous books on the history of Kilburn, Hampstead, and the surrounding areas. Their publications include Bloody British History: Camden and The Marquis de Leuville: A Victorian Fraud?

The Chrimes brothers were born into a large family in Camberwell where their father Joseph Knowles Chrimes was an insurance agent. Family historian David Chrimes has produced a well-researched website about the unusual name and its variants at: www.chrimes.org