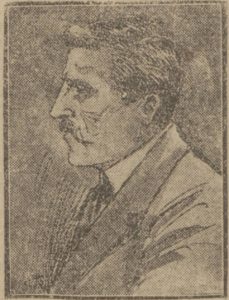

Imagine being able to see through a steel door, or to force the germination of poppy seeds and at once destroy them with the power of your mind. Such were the abilities claimed by Albert Isaac Grant of Maidstone, Kent, in the years leading up to the First World War.

Grant, a former sanitary inspector and insurance superintendent, began practising as a healer in around May 1910. His powers could not only influence vegetation but also diagnose disease and generate new internal organs. Any malady would bow to his mastery but the people who needed him most were those with consumption, cancer, or blindness.

Albert Grant was born in Bexhill, East Sussex, in 1882. He married in 1907 but, just two years later, his wife Olive died after giving birth to their daughter. Within a year of this sad event, Grant had become a self-styled ‘Human X-Ray’, able to see into people’s lungs as clearly as he could see his own hand.

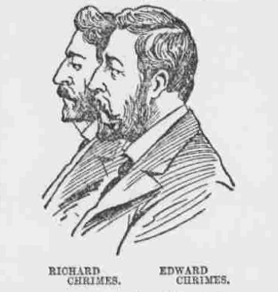

One might speculate that his bereavement had led to a mental health issue, but Grant was not alone in his remarkable ability. His brother William, nine years his junior, acquired it too and together they treated patients in the family home at Sheal’s Court, Old Tovil Road, Maidstone, with their sister Harriett providing nursing care.

For nine months, they continued in peace, but then a run of deaths brought their peculiar methods to the attention of the newspapers. Sarah Ann Winn, 68, died in February 1911 from heart failure while under the Grants’ treatment.

At the inquest, Albert Grant hinted that he had worked on his science for some years without success, but once he perfected it he managed to grow a completely new eye and a lung (presumably in a patient rather than out of thin air). He could also grow a new heart if necessary, although he had for some reason not done this for Mrs Winn.

‘I can cure any disease that anyone likes to put before me,’ Grant asserted. ‘The scientific cure is hidden to the public, but not to me.’

The saying goes that there’s no such thing as bad publicity and, via the news reports, Grant’s words reached the Sharp family of Leicester. William Sharp, a 30-year-old warehouseman, had consumption; his doctor described him as a ‘hopeless case’. He had nothing to lose by going to Kent in search of a chance of survival.

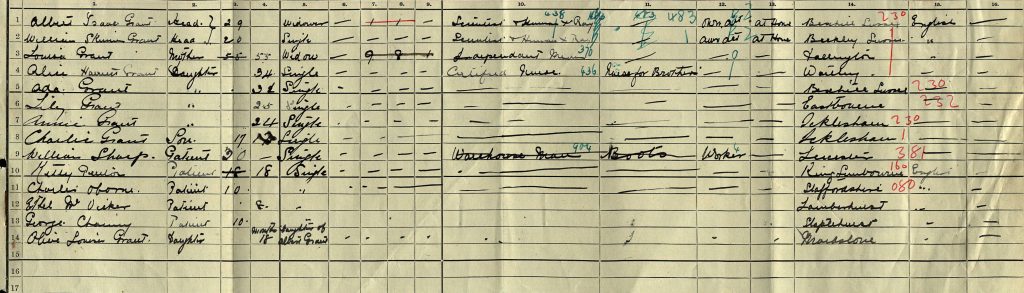

Sharp joined a cohort of five inpatients at Sheal’s Court, three of whom were children. The 1911 census lists both Grant brothers as ‘Scientist & Human X-Ray’ – perhaps the only people in the country sporting such a job title! The fee for bed, board and treatment was two guineas a week – around double what a worker like Sharp would be earning. Grant also claimed to have between 50 and 300 outpatients per day but did not charge the poor for his services.

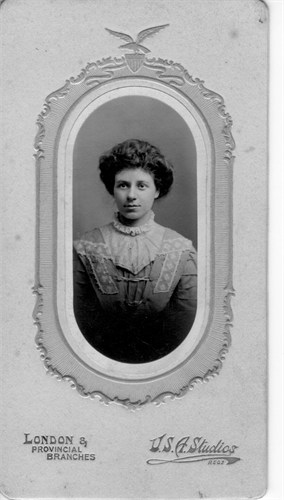

Soon, there was another arrival at the establishment – 23-year-old May Twort from the nearby village of Burham. She had tuberculosis too and this studio portrait, used by kind permission of her great-nephew, Raymond Twort, was taken just four months before her death. It is poignant to think that perhaps she and her family were already aware it could be all they’d have to remember her by. Both she and William Sharp died in June 1911.

Albert Grant was becoming a familiar face in the coroner’s court, and his testimony met with bemusement from the officials. When asked how he applied his science, ‘he made a “pass” with his hands in front of his face to illustrate his methods.’ No person living, he said, could escape his power.

‘You say you have restored a person to life,‘ commented a juror. ‘Is that person living in Maidstone?’

‘He is not alive now,’ Grant replied.

He explained the deaths by saying the patients had not been brought to him in time – he was the last resort, and if only they’d consulted him sooner, his treatment would have worked. He claimed to have kept May Twort alive ‘until her heart gave out’.

All three patients had died of natural causes and there was no evidence to suggest that the brothers had mistreated them, so no further action was taken apart from the coroner warning Albert Grant that he ‘was treading on very thorny ground.’

Grant next appeared in the papers in September 1911, when he wrote to the Board of Guardians asking for an extension of the school holidays for a blind girl, Eva Coppin, who was under his treatment.

Miss Coppin herself believed that the treatment was working – she had been totally blind but could now tell if any dark object passed in front of her eyes. The Chairman of the board allowed her to stay with Grant for an extra month, saying ‘Of course, I have no faith whatever in him, but as the poor girl has, I would be sorry to disappoint her.’

William Grant left the establishment in 1914 to get married. In October 1916 his wife had a baby girl and, 11 days later, William enlisted in the army, giving his occupation as ‘Scientist Healer’. He was fatally wounded in France in May 1918. I have not yet been able to trace what happened to his older brother.

Was Albert Grant an audacious fraudster, or did he genuinely believe he had the power to cure disease? Either way, his patients had something in common: their doctors could do no more for them. The doctors were realistic to say so – of course medicine could do nothing to cure tuberculosis or heart failure. People, however, need to have hope – and when doctors can’t provide it, there’s always someone like Grant ready to fill the gap.

Sources:

Numerous news reports including:

‘Claim to X-Ray Eye’, Cheltenham Chronicle, 4 March 1911

‘The Human X-Rays’, Dover Express, 16 June 1911

‘At X-ray Scientist’s Home’, Leicester Chronicle, 8 July 1911

‘The Human X-Rays: Alleged Cure of a Blind Girl’, Whitstable Times and Herne Bay Herald, 9 September 1911

‘Quackery’ Good Health, May 1911

Truth Cautionary List, 1912

Census and military information via ancestry.co.uk

2 thoughts on “On thorny ground: the human x-ray scientists”

Comments are closed.