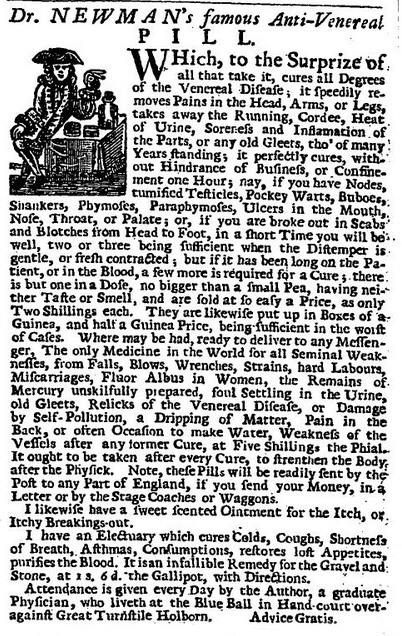

As the old saying goes, ‘A night with Venus, a lifetime with Mercury,’ and Dr Newman’s Anti-Venereal Pills were just one of a plethora of clap and pox remedies advertised in 18th-century newspapers. The relatively anonymous purchase of a pea-sized bolus offered the customer a level of secrecy, but that was by no means the only reason for preferring an advertised remedy over consulting a doctor at home.

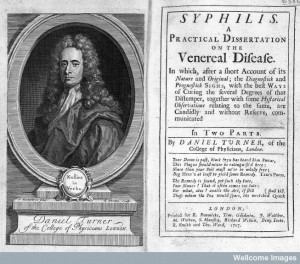

Notable physician and prolific writer Daniel Turner, in Syphilis. A practical dissertation on the venereal disease (1717) describes the standard treatment for the pox – salivation. Turner has a fluid style of writing that imparts elegance to even the most revolting of details, but the horror of the orthodox treatment shines through and sheds some light on the popularity of patent medicines.

In preparation for salivation, the patient should undergo purging medicines or bleeding and, for some, a warm bath was advisable. Women should have the treatment just after menstruation, and the temperate seasons of late spring and early autumn were the best time to carry it out – though of course it was not always possible to wait for the perfect time of year.

Turner recommends a dose of 15 grains of calomel twice a day. Initially the sufferer could expect violent diarrhoea and ‘horrid torture of the bowels,’ which in some cases would be quite sufficient to get rid of both disease and patient permanently, but after a few days came the initial signs of ptyalism – the copious production of saliva from which the treatment gets its name.

…we usually observe the Fauces to inflame, the Inside of their Cheeks to lie tumid, or high and thick, being ready to fall in betwixt the Teeth, upon shutting the Mouth; the Tongue looks white and foul, the Gums also stand out, the Breath stinks, (which is a good Omen of its coming on) and in general the whole Inside of the Mouth appears shining, seems as it were parboiled, lying in Furrows, much after the manner as it does in those who have lately held strong Spirits therein for the Tooth-ach.

By this point the patient wouldn’t be able to eat, but puking up phlegm was a good sign. While the unfortunate person was in this state, there wasn’t much the physician could do other than ‘to encourage your Patient chearfully to go on, and refresh him sometimes with a little mull’d wine.’

Turner’s experience suggested that at the high point (or low point) of the salivation, the patient could be producing up to five pints of saliva a day. This would subside and be resolved (one way or another) in about three weeks to a month.

All this, however, was just for a mild pox – a ‘stubborn and rebellious’ one would also require the patient to rub mercurial ointment into their limbs in front of the fire, and then wrap up in layers of flannel clothing. Along with the mercury, a salivating patient could expect aggressive treatment of the side effects – bleeding, emetics and laxatives were all part of the experience.

So this was the prospect if you consulted a doctor about the pox – not to mention the fact that your spouse and neighbours would find out what you had been up to.

A single, discreet dose from an advertiser seems not so much the preserve of the gullible as the self-preservation of the wary.

“any old gleets” !

what a wonderful turn of phrase. It would have made a great title, with or without pockey warts, buboes, and shankers.

thanks for another entertaining and enlightening post

Hey, I don’t give titles to just any old gleets, you know. 😉

Delighted you enjoyed the post!

Hi:

Such interesting blog.

I’m physician. I like history and of course medicine history.

Nice to find your blog.

Regards from Spain

What a horrid treatment. I just found this blog- I am fascinated by old medical treatments and history in general. I wonder if in a couple of centuries when we have found much more effective and less brutal cancer treatments will people be remarking in horror upon chemotherapy?