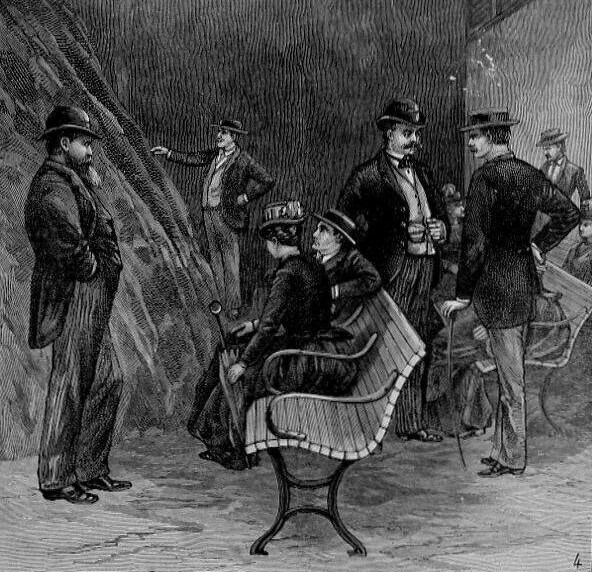

‘Just imagine 16 or 20 people leaning against a rock in all manner of positions. Some put their heads against it, others their feet, and again others their hands or back. All waiting, some with faith, and some without any, for the shock or electrical sensation that comes to all sooner or later.’

The reporter from the Washington Chronicle (Washington-Wilkes) had experienced for himself the wonders of a stay at the Electric Shaft in Taliaferro County, Georgia. The shaft – an excavation into the mountainside – gained fame in the 1880s for its power to cure rheumatism and other musculoskeletal disorders. People travelled from all over the US in search of healing.

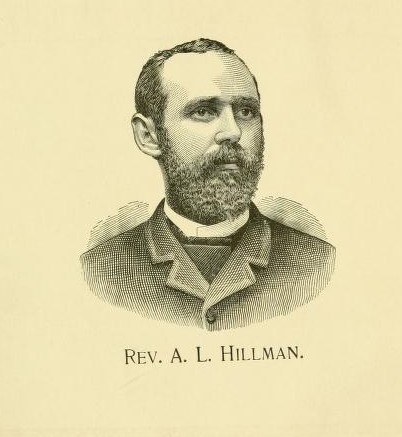

Like many unexplainable therapies, the Electric Shaft had an origin story imbued with mystery and serendipity. Farmer and Baptist minister Andrew L Hillman was prospecting on his land in the hope of finding alum, when he experienced a strange feeling, akin to a shock from a galvanic battery.

‘Sometimes,’ the Richmond Dispatch reported him as saying, ‘the hands could hardly hold the drill.’

Although only in his 30s, Hillman suffered from rheumatism and dyspepsia. As he drilled through the rocks, he noticed the pain disappearing. ‘I persevered,’ he said, ‘and found myself restored to perfect health.’ During his excavations, he also uncovered a source of mineral water and created an underground well.

Hillman had to go to Atlanta for a few months, but the curative potential of the rocks preoccupied him, and he revisited the site on his return. As local people began to find relief from their ailments, the press picked up the story and soon there were more visitors than Hillman could accommodate. The treatment was simple: drink the mineral water and then sit in the mine shaft until you felt tingling sensations, or perhaps even an electric shock. Sometimes, patients became ‘overcharged’ with electricity and ended up unconscious, but invariably reported feeling better once revived.

The rural area was beautiful but lacked amenities, and although Hillman put up some sheds near the shaft, they were not very comfortable for people who had travelled a long way with painful symptoms. He wanted to close it until he could offer a more pleasant experience, but visitors begged him not to turn them away. They would put up with anything for the sake of a cure, they said. Some even slept in the shaft.

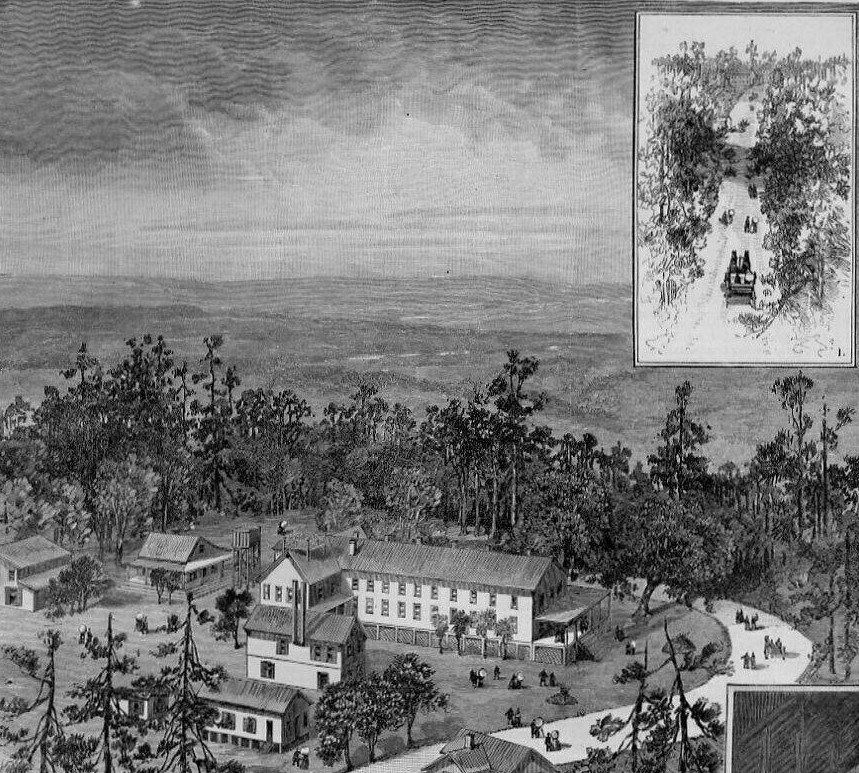

In December 1887, Mr Hillman and several others established the Georgia Electric Mound Company, which formally took control of the shaft and surrounding land with the aim of establishing a popular resort. In due course, they built a 44-room hotel and visitors could now enjoy their stay in comfort. The two-storey building was richly kitted out with marble-top furniture, luxuriant carpets and bathrooms on each floor, with an experienced hotel manager ensuring everything ran smoothly. Its own vegetable gardens and the local farms provided the kitchen with fresh and healthy ingredients. Visitors of more limited means could stay in new boarding houses, and a railway depot and post office sprang up nearby. The emerging village was named Hillman.

By this time, Mr Hillman had found an immense rock on the other side of the mountain that appeared to have the same electrical properties as the original shaft. Nearby were two mineral water springs, which became known as the Magic Well and the Nausea-Cure Spring, offering visitors further help for their illnesses. In small doses, the Nausea-Cure water would see off stomach bugs and sea-sickness – but the drinker had to be careful, because too much would produce nausea. There was an element of ‘like cures like’ in the theory of the water’s efficacy.

One had to be fairly sociable to take advantage of the resort’s treatment – it involved sitting in the electric room for hours with all and sundry, and it’s easy to imagine the inevitable obnoxious person ruining the experience. Even more off-putting to the introvert was the practice of forming a hand-holding circle to allow the electricity to flow between people. For some guests, however, this was all part of the fun. Mrs J J Birch, who took her sick daughter Lillian there in 1893, had ’a very pleasant time in conversation with friends,’ and highly recommended the resort to the editor of her local paper.

Mr Hillman himself, ‘a quiet young Baptist minister’, was perhaps a reluctant proprietor, motivated mainly by a desire to share his discovery with those who were suffering, and he did not go in for ostentatious advertising. In 1889, he sold the resort to James A Benson, who appears to have already been involved in some capacity, for $8,000.

Unfortunately, the luxurious hotel burnt to the ground in March 1901, seemingly due to a defective flue. Perhaps its fortunes were waning by then, as there was only one guest in residence. He was rescued by the manager, Charles Dozier, and there was no loss of life.

Whatever the merits of sitting in a cave for several hours a day, the Hillman Electric Resort in its heyday offered a well-appointed hotel, good wholesome food and picturesque landscapes. They say a change is as good as a rest, and a relaxing holiday probably did help some people feel better, even if the electrical benefits were unsubstantiated.