Sometimes, patent remedies killed people. The Live-Long Candy did manage to get mentioned at an inquest, and there’d be a particular irony in a product of this name carrying someone off – but I reckon it’s innocent.

Eight months before this ad appeared, 16-year-old Belinda Balls, housemaid to Mrs Waspe at Gusford Hall in Suffolk, was suffering abdominal pain. This was nothing new for her, but as she hadn’t been in her job very long, she tried not to make a fuss. On Saturday 24 March 1888, however, she was in such agony that she had to ask her fellow servants for help.

The cook, Jane Mallett, gave her a cup of ginger and Belinda struggled on with her work. By ten o’ clock that evening she was in serious trouble. Her mistress gave her some hot water, which made her vomit, and she went on to have a bad night, cared for by Mrs Mallett in their shared room.

On Sunday, Belinda took some ‘family pills’ (laxatives) to no avail, and had to stay in bed all day. That night, Jane Mallett sat up with her until she fell asleep, then helped her when she fell out of bed at four o’ clock in the morning.

When the cook next awakened at dawn, she was shocked to find her young companion dead.

Mr G H Hetherington, surgeon to the East Suffolk hospital, examined the body and found it to be ‘that of a woman well developed.’ Other than this observation, he could pass no comment until he had done a post mortem examination, when he discovered severe ulceration of the stomach. In his opinion, the cause of death was peritonitis. Mr Hetherington felt that Belinda’s habit of taking Live-Long Candy after meals had exacerbated her disease. Such quack remedies, he said, tended to alleviate the pain, but would cause constipation and ultimately be harmful. The implication was that the Live-Long Candy contained opium – but no analysis was carried out.

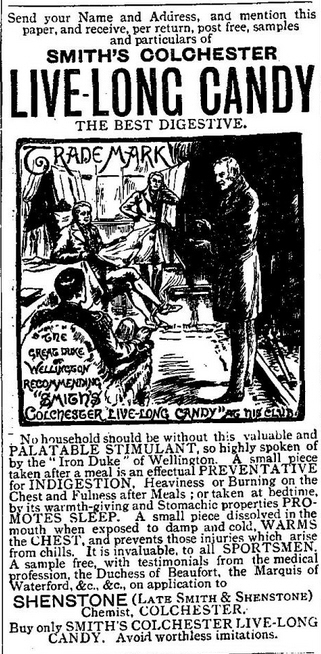

The Candy’s proprietor, J C Shenstone, at once wrote to the Essex Standard to set the record straight. The recipe had been around for 50 years, he said, since his predecessor Thomas Smith brought it to public attention and gained the endorsement of the Duke of Wellington. You might expect a dodgy practitioner to leap to an immediate and hysterical defence of his practices. Shenstone, however, defied any accusations of quackery by being completely reasonable and failing to threaten to sue anyone.

Shenstone was a dispensing chemist with premises on Colchester High Street. In around 1834, the shop had been established by Thomas Smith, who began selling the Live-Long or Digestive Candy a few years later. Certainly by 1844 he was doing a brisk trade in the stuff, and at around the same time employed an apprentice, James B. B. Shenstone, (a descendant of the 18th-century poet William Shenstone) who travelled all the way from Bath to take on the role. After his apprenticeship, Shenstone started his own business at Wells in Norfolk, but later returned to Colchester as junior partner to Smith. Thomas Smith died in 1864 and the business, including the Live-Long Candy recipe, went into the Shenstone family.

Henry Beasley, in The druggist’s general receipt book, gives the recipe as follows:

Powdered rhubarb, 60 grs.

Heavy magnesia 1oz.

Bicarbonate of soda 1dr.

Finely powdered ginger 20 grs.

Cinnamon powder 15 grs.

Powdered white sugar 2oz.

Mucilage of tragacanth q. s.

Beat together, and divide into parallelograms of 20grs. each,

The younger Shenstone’s letter was no-nonsense but polite. He offered a £200 reward to anyone who could prove that the product contained opiates or any other ingredient likely to cause constipation. He stated that he was ‘quite prepared to satisfy Dr. (sic) Hetherington privately as to the nature of all the ingredients used in the preparation,’ and included a note from the physician and surgeon of Essex and Colchester Hospital saying they had used the candy and found it beneficial. This could all have been done in an arsey passive-aggressive way, but in my opinion the tone of the letter is assertive but calm; an understandable response to someone who had made unfounded assumptions about the nature of the remedy.

Just a few months later, Mr Hetherington had more pressing matters to think about when his vehicle was overturned by a runaway horse – but perhaps that’s another story.

.

.

————————————————————————-

Thank you to everyone who has voted for The Quack Doctor as Best Literary Medical Weblog in the Medgadget Awards! If you haven’t voted yet and would like to, polls are open until 12 midnight (EST) on Sunday 13 Feb. For once in my life I would like not to be the wheezy unpopular kid trailing at the back, so if you can sling a vote my way I’d be very happy!

Thank you to everyone who has voted for The Quack Doctor as Best Literary Medical Weblog in the Medgadget Awards! If you haven’t voted yet and would like to, polls are open until 12 midnight (EST) on Sunday 13 Feb. For once in my life I would like not to be the wheezy unpopular kid trailing at the back, so if you can sling a vote my way I’d be very happy!

.

.

.

Sounds like it was a combination laxative/ antacid. Probably quite useful after a 19th C. meal of fats, starches & tough meat.