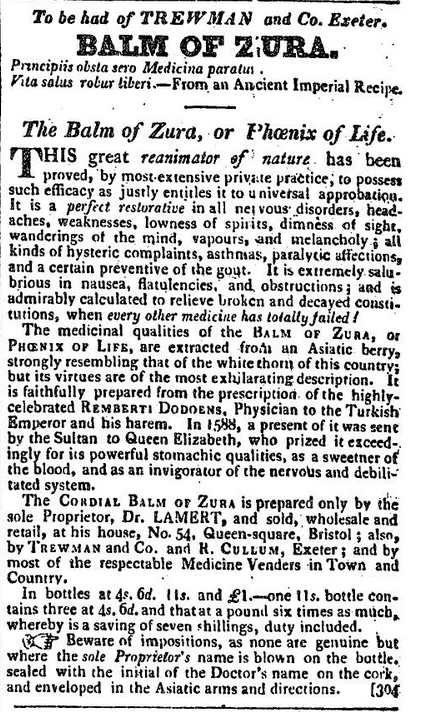

Source: Trewman’s Exeter Flying Post, 3 April 1823

Much of the evidence on this one is anecdotal, but the proprietor of the Balm of Zura, Dr A. Lamert, certainly sounds quite a character.

Lamert was the son of a London-based German quack who dabbled in ophthalmology before moving on to selling a Nervous and Rheumatic Balsam and treating venereal disease.

While Lamert senior worked solely from his Spitalfields address, his son branched out, setting up a dispensary in Bristol and travelling the country, announcing in each town’s newspaper that the lucky denizens were to be favoured with a visit. In the first four decades of the 19th century he went far and wide, taking in Derby, Ipswich, Glasgow, Aberdeen, Newcastle, Falmouth, Exeter, Manchester and plenty of other places in between. While at Ipswich in 1811 he received some anonymous hate-mail with a Bury postmark. His dad advertised in the Bury and Norwich Post offering a 30 guinea reward for identifying the culprit, but the residents of Bury appear to have remained silent.

Lamert Jnr was the ostentatious variety of quack who flaunted his wealth and took every opportunity to publicise his miraculous cures. The Citizen (October 1 1829) described him as:

…a fearfully dashing gentleman, all powder, with a black servant, and drives a beautiful pair of greys. Vive la quackery!

…while the Medical Adviser in 1824 was typically indignant:

All Devonshire, and the next fifty counties, does not produce so arrant a humbugger as this: he is powdered from the occiput to the coccygis,—from one shoulder to the other —from the cape of his coat to the buttons of his waist,—a curricle a-la-Jordan, an eyeglass,—a bamboo, and a copper face. Thus he parades about, all outside, while if you tapped him upon the head it would sound like a drum, —so hollow, so empty, so brainless is the wight.

(‘a-la-Jordan’ refers to the proprietors of the Cordial Balm of Rakasiri.)

One of Lamert’s innovative ways of increasing his fame was to attend the theatre and, during the performance, instruct a servant to call out that he was wanted for some medical emergency.

‘These interruptions,’ grumbled the Medical Adviser, ‘always happen when some interesting part of the play is going on.’

Lamert’s theatrical connections, however, were not confined to sitting in the audience. In his youth he had sung at the Royalty Theatre in Whitechapel, but after being pelted with oranges, he changed his career path and went on to follow in his father’s footsteps as a quack.

His arrogance might have made him capable of drawing attention, but this was often from pranksters rather than admirers. In 1848, (after Lamert’s death) an anti-quackery lecturer called Mr Richardson told of a student going to consult the doctor, pretending to be deaf. Lamert, assuming he would not be heard, ‘made some very free remarks on the character of the student’, who soundly thrashed him and went on his way.

The Medical Adviser (who, once they had it in for a quack, didn’t tend to let up), tells the tale of a dissatisfied customer who – not quite literally – gave Lamert a taste of his own medicine. The patient had wasted £5 on the Balm of Zura and received no benefit, so he took the empty bottle along to a tavern where Lamert was regaling the drinkers with a song. When the doctor ‘had occasion to absent himself a short time from the company,’ the joker pissed in the bottle and topped it up with brandy and water. On Lamert’s return he complained to him that his last purchase of Zura had gone sour.

As the doctor tasted the mixture, a couple of the tavern-goers were ‘necessitated to quit the room, to give vent to their risible titillation.’ Then someone pretended to get angry that the sour mixture might be poisonous, so Dr Lamert drank the whole bottle in proof of its safety, to the hilarity of all concerned.

They let him in on the joke and the original prankster ‘prudently decamped’ in the face of his wrath.

.

.