John Michael Smith is one of those fleeting figures who cross history’s pages when they get into trouble and then disappear, leaving only a hint of a life where destitution is more prominent than criminality. At the age of 11 he lived in Lodge Lane, Derby, with his mother and siblings. His dad died in 1909 and, a year later, after a policeman found John in a neglected state, the NSPCC induced the family to go into the workhouse. They immediately decided to leave, and in September 1910, John got caught stealing a bottle of Hall’s Wine. The courts sent him away to Clifton Industrial School in Bristol to remove him from the bad influence of his mother, whom the NSPCC inspector considered ‘not a desirable person to have the care of him.’

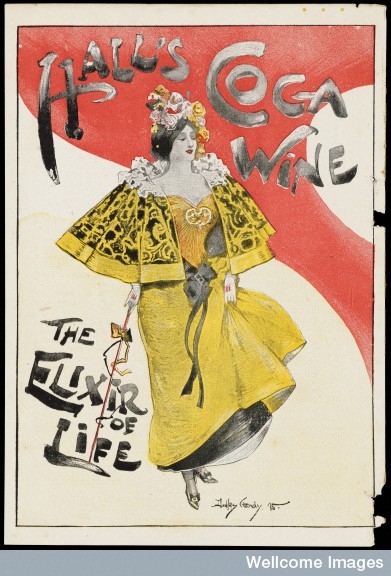

What was this elixir for which John risked his liberty?

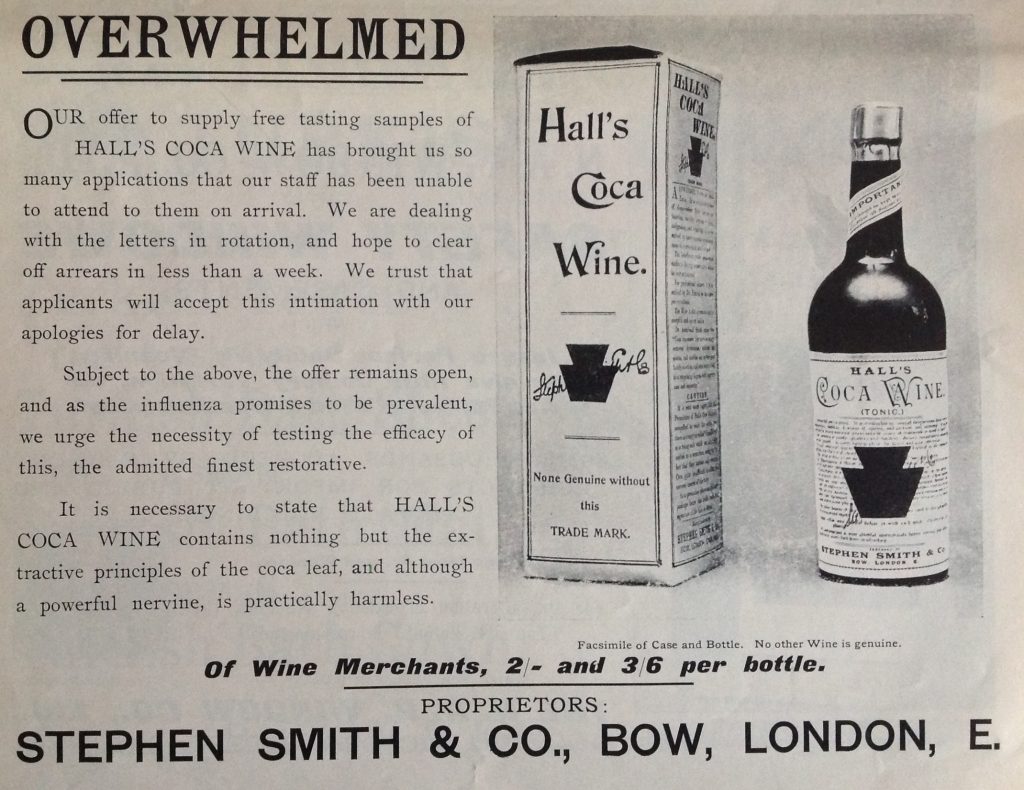

Hall’s Wine was one of the proliferation of late-Victorian ‘nervine’ drinks that contained cocaine. Consisting of Old High Douro and Priorato port with extracts of the plant Erythroxylum coca, the product was introduced in 1888. In promoting it, however, Henry James Hall (trading as Stephen Smith & Co) soon discovered that he was popularising coca in general and boosting sales of inferior competitors. It was also not possible to register the words ‘coca wine’ as a trademark, so in 1897 the name changed to ‘Hall’s Wine’ – not to hide the fact that it contained cocaine but to strengthen Hall’s as a brand. Adverts claimed the wine was ideal for those times ‘When you are neither one thing nor the other‘, and would restore ‘the last five or ten percent of health, without which all is dulness.’

Approving write-ups in the Lancet and the British Medical Journal gave Hall the material to promote his wine as the doctors’ choice. Before the turn of the 20th century, however, some medical writers had begun to express reservations about the unregulated sale of such products.

The focus of their criticism was not – as might be supposed from a modern perspective – the presence of cocaine. It was the ‘wine’ part of coca wine that apparently caused more trouble. Teetotallers, claimed Frederick C Coley M.D. in 1898, were blithely knocking the stuff back while congratulating themselves on their commitment to temperance.

The 1912 parliamentary Select Committee on patent medicines highlighted the same concerns. Sir Thomas Barlow, President of the Royal College of Physicians, had no doubt that ‘the prescription of medicated wines is in some cases responsible for the starting of the drink habit, especially in women.’ An anonymous contributor to the reports warned that: ‘The devil in disguise is more dangerous than the devil with his fork and tail.’ He was referring to alcohol, not what would now usually be considered the more harmful drug.

But did people genuinely not realise that coca wine was… well… wine? Some commentators were more cynical about the idea of teetotallers innocently mistaking it for a ‘temperance drink’. For one West End doctor interviewed by the Daily Mail, drinkers were finding coca wine ‘an excellent way to swallow their principles and their alcohol without endangering their reputations as total abstainers.’

‘Remember,’ he said, ‘that it is not the cocaine that is the dangerous element.’ Perhaps young John Smith was not a coke addict at all, but just trying to gain respite from his situation in the time-honoured embrace of booze.

Sources:

‘Children’s Court’, Derby Daily Telegraph, Monday 26 September 1910 at British Newspaper Archive

Report from the Select Committee on Patent Medicines, together with the proceedings of the committee, minutes of evidence, and appendices. 1914, (414) IX.1

‘The Dangers of Coca Wines’, British Medical Journal, Vol. 2, No. 1927 (Dec. 4, 1897), p. 1666

‘Coca Wine and its Dangers’, British Medical Journal, Vol. 1, No. 1884 (Feb. 6, 1897), p. 353

‘The Composition of Some Proprietary Food Preparations’, British Medical Journal Vol. 1, No. 2526 (May 29, 1909), pp. 1307-1309

Coley, Frederick C. ‘Medicated Wines’ British Medical Journal, Vol. 2, No. 1967 (Sep. 10, 1898), pp. 715-716

Wellcome Image of the Week: Hall’s Coca Wine

‘Hall’s Coca Wine: Medical testimonials and analysis’ c. 1892, John Johnson Collection

‘When you are neither one thing nor the other’, The Graphic, 7 July 1900

‘Abstainer’s awful death’ Daily Mail, 12 February 1897

“‘Remember,’ he said, ‘that it is not the cocaine that is the dangerous element.’”

Ah, the good old days.

@undine

yes the good old days ( I was thinking the same 😉 )

Why does this article fail to mention the actual cocaine content per fluid ounce?

IIRC Hall’s had about 35 mg per fluid ounce, of the isolated alkaloid.

More established products as Vin Mariani contained about 6 or 7 mg per fluid ounce and were made from whole Coca extract.

A stronger version “Elixir’ Mariani may have contained 15 mg per fluid ounce, made with Coca extract but fortified with isolated cocaine.

Any article concerning the abuse potential of such products should not leave such facts out.