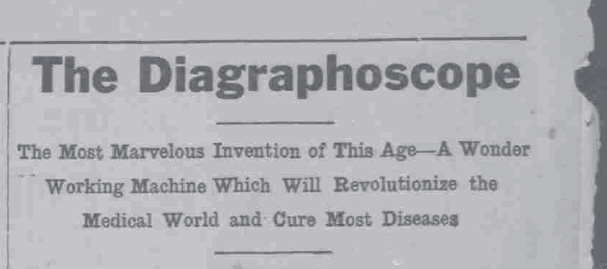

Twentieth-century businessman X. W. Witman saw a lot of potential in X-rays. Doctors might get excited about their emerging medical application, but for him X-rays offered something even better – the chance to get rich quick. If you could X-ray Witman’s head, the plate would display a fine collection of dollar signs.

Adverts puffed his Diagraphoscope as the eighth wonder of the world – a marvellous invention whose force ‘... is doing more for diseases than an ocean of drugs or a forest of surgeons’ knives.′

Trading as the Advanced Medical Science Institute, (or the Ozona Company, or one of several other names), Witman and his associates took the machine on tour, setting up temporary offices in well-populated towns and moving on – sometimes rather quickly – when the time was right.

A window to the human body

The Diagraphoscope of the adverts was a wonder indeed. A screen made of a mysterious compound ‘which costs in the rough just five times its weight in gold,′ it emitted rays so powerful that they could pierce three feet of solid wood to reveal a copper cent on the other side. Nevertheless, they were harmless to the human body. When suspended in front of a person, the screen’s ‘radio forces’ kicked into action to reveal the detailed 3D image of every internal organ. The beat of the heart, the rise and fall of the diaphragm, hidden bullets, gallstones and kidney stones appeared so clearly that:

‘..it all makes the formerly vaunted X-ray look like a toy.’

Too complicated for doctors

One might expect such a groundbreaking invention to have been the talk of the medical world, so why in October 1911 was the US’s only Diagraphoscope holed up in room 303 of the El Paso newspaper offices?

Witman had an answer for that. The enormous cost of the machine was beyond the means of hospitals, and to become an expert Diagraphoscope operator required ‘a long course of arduous study′ that most doctors simply couldn’t hack.

By implying that his contraption was too advanced for them, Witman was using the perennial technique of discrediting the medical profession – but he also sought to align himself with them by claiming that his discovery astounded eminent doctors. His adverts relate the outcome of a (presumably fictional) demonstration in New York City, where ‘The usual calm physicians broke into expressions of astonishment,′ at the sight of a patient’s innards in all their visceral glory. They lauded the machine’s operator for his ‘almost supernatural faculty of accomplishing that which lesser mortals have deemed impossible.’

Not all it’s cracked up to be

Karl E. Murchey, of the Vigilance Committee of the Associated Advertising Clubs of America, found the Diagraphoscope rather less impressive. He described it as a circular tube full of coloured liquid, an ordinary photographer’s hood through which the practitioner viewed the patient, and an electric buzzer to provide appropriate sound effects. Murchey related that in an unnamed town, the Diagraphoscope diagnosed a ‘mystery shopper’ with a micro-organism of the stomach. This terrible condition was akin to cancer, but – thank goodness! – he was just in time to be saved. His evidence resulted in a warrant for the practitioner’s arrest, but the Advanced Medical Science Institute skipped town on the morning of the hearing.

A Six Million Dollar Man?

In spite of the Diagraphoscope’s miraculous properties, its purely diagnostic function left scope for the Institute to develop separate therapeutic devices. A plethora of other inventions shared Witman’s battered travelling trunk, including a ‘multiple machine’ that could almost raise the dead.

In 1912 an advert described the case of Herbert Beatty, preparing to meet his maker after a motorcycle accident. The Institute provided him with a glass eye, an artificial nose, a silver plate in his skull and a false lining in his stomach. The latter was deposited ‘by a powerful current which is perfectly harmless and painless; bismuth is used, as that metal can be removed after a cure by simply reversing the polarity of the current.’

Louisville isn’t fooled

Witman made an effort to keep his company within the law by employing a registered physician, Dr George W. Foreman, who had graduated from Kentucky Medical School in 1902. And it was in Kentucky in 1912 that the Diagraphoscope’s luck ran out. Adverts in the Louisville papers attracted attention from the State Board of Health and Witman, Foreman and two others were arrested on 18 counts of failing to file certificates naming those conducting the business, and two counts of practising medicine illegally. Witman received fines totalling $700. After a grilling by the court, George Foreman was fined $50, while the cases against the other two were dismissed. Within an hour, the offices had closed down – a good result for Louisville, but the cynical Journal of the American Medical Association predicted that the Advanced Medical Science Institute would soon pitch up in another unsuspecting town.

The Diagraphoscope might not have rendered X-rays obsolete, but Witman’s advertising did foreshadow one modern development. These words of wisdom from 1911 would not look out of place if they were typed in Comic Sans against a garish background and spewed into your Facebook timeline by some loser you hated at school:

People who say ‘It can’t be done’ are interrupted by some one doing it.