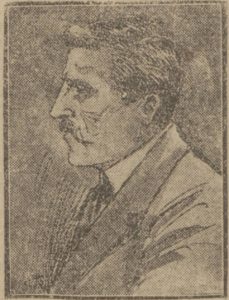

A deaf person seeking treatment in 1850s London appears to have had plenty of options, judging by these advertisements in Reynolds’s Weekly Newspaper. The only problem was, the advertisers all belonged to the same gang – and if you knew what was in their medicine, you would not let it anywhere near your ears.

Multiple ads under different names were a mid-19th-century scam that I’ve written about before. A patient might well try more than one practitioner in their search for a cure – so if one person posed as all those doctors, he could take the same victim’s money time and again.

Patients consulting by post from outside London were a good source of income, but those visiting in person posed more of a risk. The quacks had to keep up with who they’d seen under which alias, otherwise things could go badly wrong…

In 1857, Miss Mary Scattergood visited ‘Surgeon Coulston’ in response to an advert that promised a cure in ten minutes. She soon discovered that this came at the extortionate price of ten guineas, which she could not afford, but she agreed to pay five on the proviso that a hearing apparatus was part of the deal. She expected to undergo some procedure that would have an immediate effect, but Coulston sent her away with a bottle of mixture instead. By the next morning, he told her, she would certainly be cured – though he continued with less certainty by saying ‘Use it again the following night in case you are not.’

The mixture gave Miss Scattergood sore ears and a headache – added to which, she had never got the apparatus she paid for, so she returned to Coulston’s premises. He wasn’t there, and his assistant (who considerably resembled him) said he had gone away for a few days.

Miss Scattergood called again several times but the assistant eventually told her Coulston had gone to Madeira, so she had to wave goodbye to her five guineas and put this one down to experience. It wasn’t until about two years later, when she accompanied a friend to an ear-doctor called Dr Matton (or Dr Watters according to some reports), that she discovered it was the same bloke – and this time she wasn’t going to let him get away with it.

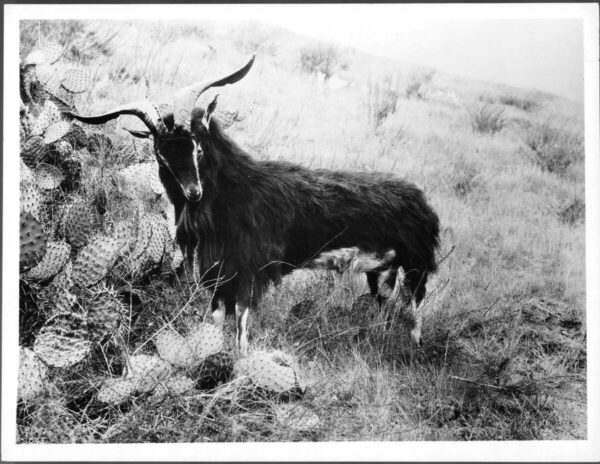

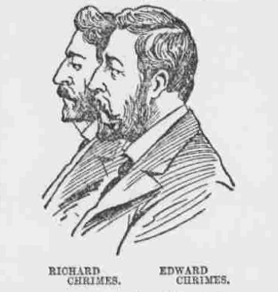

Coulston/Matton/Watters’ real name was John Gibson Bennett, and he and his younger brother William were former card-sharpers now running a multiple-ad scheme along with a few other dodgy characters. William recognised Miss Scattergood and made a rapid exit, but she had seen enough. She had the older Bennett summoned to Westminster County Court, and other witnesses came forward to testify that he had conned them too – one man told how Bennett had called him a ‘grey-headed old rascal’ and threatened to throw him down the stairs.

J G Bennett, who ‘wore a moustache, and appeared to be about 40 years old’ denied everything, claiming never to have seen Miss Scattergood in his life. William, who also wore a moustache and was about ten years younger, tried to pin the blame on the non-existent Surgeon Coulston, but the judge ruled in favour of Miss Scattergood – she got back her five guineas and J G Bennett was indicted for perjury.

He didn’t turn up to his hearing at Bow Street Police Court, but some interesting evidence came out. The prosecutor, Mr Bowen May, acted on behalf of a newly formed anti-quackery society called the London Medical Registration Association, which had helped Miss Scattergood bring Bennett to trial. This Association had performed an analysis on Bennett’s mixture and found it to comprise urine and alum. A former porter to the gang told of a ‘place where urine was kept’ and that he had helped to make up the bottles (he was only doing his job, guv).

Then Claude Edwards, the Bennetts’ factotum, described how John and William Bennett both posed as Dr Watters even though there was a real Dr Watters involved too. In one incident, the younger Bennett left Edwards to treat a patient while he went to the pub, only returning to collect the money and saying ‘I think I must let Mr King off for twelve guineas, but if I can drop it into him for more I will.’ Mr King ended up paying more than 30 pounds for what he was told was a traditional remedy discovered by ‘Dr Watters’ in China or Japan.

The magistrate issued a warrant for the arrest of both Bennett brothers, but by then their whereabouts ‘appeared somewhat uncertain.’

Although the Bennetts had legged it, the law later managed to catch up with other members of the gang. That’s a story for another post, but during one hearing, Edwards confirmed that the brothers’ liquid medicines were mainly urine and that their powders were nothing but sawdust.

.

.

(Note: The court hearings were reported in numerous newspapers and the quotations above are repeated in several sources, but some examples are The Morning Chronicle 10 February 1859 and The Era 6 March 1859)

One thought on “The Ear-Doctor Fraud”

Comments are closed.