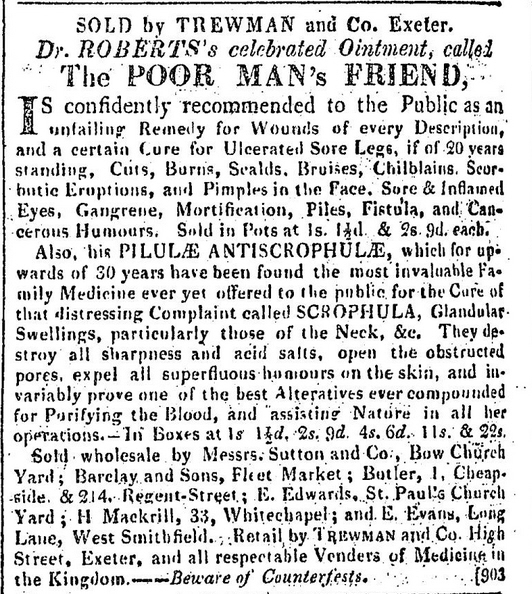

Source: Trewman’s Exeter Flying Post, 20 July 1826

In 2003, the Daily Mail ran a story titled: Beeswax is ‘miracle’ cure. The article referred to an 18th/19th-century ointment called The Poor Man’s Friend, a popular remedy for wounds and skin conditions. The reason it hit the 21st-century press was that its inventor’s original secret recipe had come up for auction.

Giles Laurence Roberts, proprietor of the Poor Man’s Friend, didn’t have a great start in life. Born in April 1766 in Bridport, Dorset, he contracted smallpox when he was nine months old. Although he recovered, he then got rickets and was unable to walk until the age of five.

Young Giles, however, pulled through, and by his early teens had developed a keen interest in medical botany, studying Culpeper and formulating his own herbal medicines. He achieved some local fame as a healer, particularly for cases of fever and ague, and was also fascinated by electricity, conducting experiments with a homemade electrical apparatus. Unable to make it work at first, he persevered and eventually managed to give himself an electric shock.

At 18, he went to work for a mechanic, but his master soon died and Roberts expressed a wish to become an apothecary’s apprentice. His family didn’t approve and he ended up in Bristol working for an optician. Sharing his lodgings was a respectable surgeon called Mr Pitt, who encouraged him in his interest in healing and anatomy.

Back home in 1788, Roberts set up shop as a druggist and, although unqualified, began practising as an apothecary. After six years’ successful business, he travelled to London to study Anatomy and Midwifery, attending lectures at Guy’s and St Thomas’s, and only a year later arrived back in Dorset as a fully licensed surgeon, apothecary and accoucheur. Only one thing was missing – the title ‘Doctor.’

King’s College Aberdeen awarded him a medical degree on 20 April 1797 – this appears to have been arranged by his tutors in London, and he did not have to do any further study or pass exams. Aberdeen was well-known for awarding medical qualifications on receipt of cash, so it’s possible that some money changed hands. Dr Roberts’s background of diligent study, however, made him far more deserving of his new title than many of the ‘Doctors’ featured on this site.

His successors describe his physical appearance as follows:

He was short in stature, being only about five feet high, dark complexion, a beautiful black eye, and in his younger days long black hair falling on his shoulders. In his dress, and appearance generally, he was singular and original, bearing mostly the character of a Quaker or Friend.

He began selling his own branded remedies at the end of the 1790s, starting with the Pilulae Antiscrophulae for scrophula and scorbutic eruptions. The Poor Man’s Friend remained a local product until about 1820 when it got an endorsement from an aristocratic patient and sales took off.

During the 1820s, Roberts began publishing a yearly pamphlet called the The annual mentor; or, Cottager’s companion: comprising concise maxims and golden rules for preserving the mind and body in health, and conducive to wealth, long life, and happiness, a Friend to the Poor, and a Companion for the Rich.

It’s no surprise that this free publication was mainly a plug for the Poor Man’s Friend and the Pilulae Antiscrophulae. At 32 pages, however, it contained a lot of other useful information. Short essays gave advice on health issues such as personal hygiene:

If dirty people cannot be removed as a common nuisance, they ought at least to be avoided as infectious. Superior cleanliness sooner attracts our regard than even finery itself, and often gains esteem where the other fails.

and there were lists of Wholesome Counsellings, including:

He that will not sail until all dangers are over, must never put to sea.

An ass was never cut out for a lap-dog

The wise man even when he holds his tongue says more than the fool when he speaks.

Marriage is a feast where the grace is sometimes better than the dinner.

There were also articles on choosing a wife, on the slovenly practice of burning green wood, on how to escape from a fire, and many more aspects of life. Although on the surface this all sounds tediously didactic, the information was presented in an engaging, accessible way that doesn’t come across as too worthy, and it beats Britain’s Got Commercial Breaks for an evening’s entertainment.

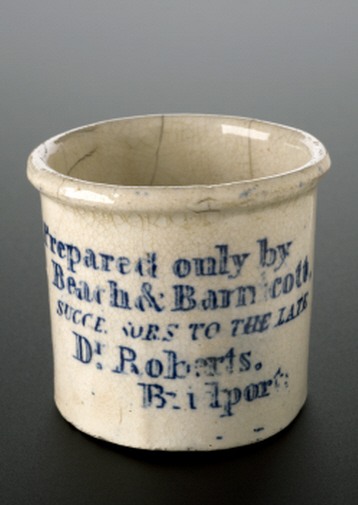

Roberts remained in Bridport for the rest of his life, dying in 1834. He left the recipes to Thomas Beach and John Barnicott, who took over the shop – the building is now Grade-II listed and houses a restaurant called Beach & Barnicott.

Roberts remained in Bridport for the rest of his life, dying in 1834. He left the recipes to Thomas Beach and John Barnicott, who took over the shop – the building is now Grade-II listed and houses a restaurant called Beach & Barnicott.

Roberts was in the middle of compiling the 1835 edition of the Annual Mentor when he died. Beach and Barnicott went ahead with publication, but in a shortened 24-page format. Later editions were reduced to 12 pages, most of which was adverts and testimonials. There were still a few general articles to draw the reader in, but the publication didn’t have the same entertainment value as when Roberts was alive.

The Poor Man’s Friend remained available until the mid-20th century, but made the news in 2003 when Bridport Museum bought the secret recipe for £480. Its composition, in the words of the Daily Mail, was ‘nothing more than 95% lard and beeswax’. Nothing, that is, except the other 5% – a fragrant but dangerous concoction of mercurous chloride, sugar of lead, mercuric oxide, zinc oxide, bismuth oxide, red pigments and oils of rose, bergamot and lavender.

Above right: Mid 19th-century dispensing pot. Photograph courtesy of the Science Museum, London.

Oh dear a toxic concotion of posion mixed with wax doesn’t sound like a very good ‘friend’ to me! Great post very informative- thanks!

Glad you liked the post!

It seems 95% friendly sometimes just isn’t enough!

I used to work in Beach’s Chemist shop 1954-56.We would make up Batches of “POOR MAN”S FRIEND’ maybe yearly depending on demand.

The oily heavier ingredients were heated and the rest added.It was poured hot(by me) into small jars.If underfilled then topped up with the heated unguent for a smooth look.

The labels I then applied.I also packaged and posted the parcels.

anne

Thanks for commenting, Anne – it’s lovely to hear a first-hand account of the product.

The Dr Roberts/ Beach & Barnicott pharmacy was never on these premises. They traded under various owners from 1788 until the 1960’s at 9 East Street at the old George Inn now the Cancer UK Charity shop.

Visit the Dr Roberts Gallery in Bridport Museum or the Local History Centre in Gundry Lane for more information.