..

What is any self-respecting quack to do in the face of criticism?

The answer in 1804 was exactly the same as it is now – turn nasty and threaten to sue the arse off everyone.

The name ‘Ching’s Worm Lozenges’ might suggest that this will be an icky-parasite post, but in a way I wish it were. Instead, this story is incredibly sad.

There were two kinds of lozenge – yellow and brown – that had to be taken at different times of day. Both contained white panacea of mercury. The travelling sales agents, however, were under strict instructions to assure customers that ‘not a single particle’ of mercury was in them.

On 4 December 1803, a little boy called Thomas Clayton, aged 3, was given the Lozenges, followed three days later by a repeat dose. He went into a high state of salivation – one of the symptoms of mercury poisoning. His parents sent for medical help, but to no avail.

.

…the mouth ulcerated, the Teeth dropped out, the Hands contracted, and a Complaint was made, of a pricking Pain in them and the Feet, the Body became flushed and spotted, and at last Black, Convulsions succeeded, attended with a slight delirium; and a Mortification destroyed the Face, which proceeding to the Brain, put a period (after indescribable Torments) to the life of the little sufferer, on Sunday, the 1st instant, Twenty-Eight Days after he had taken the Poisonous Lozenges.

The coroner’s verdict was ‘Poisoned by Ching’s Worm Lozenges’ and the above description is from a handbill written by the child’s father, also called Thomas Clayton. Clayton was a printer and bookseller, so was able to produce loads of these leaflets and personally deliver them all around his local neighbourhood in Kingston-upon-Hull. In them, he noted that the main Hull papers (the Packet and the Advertiser) had ignored both the death and the coroner’s verdict – probably because they received so much advertising revenue from Ching’s.

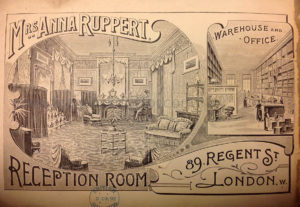

John Ching himself had died in about 1800. The business was ostensibly carried on by his widow, but really came under the control of a dodgy cove called Mr Butler.

Signing himself R. Ching, Butler responded with a broadside of his own, attacking the grieving father and threatening to prosecute him for publishing the case. He called Clayton’s words ‘malicious invective,’ ‘AN INFAMOUS ASSERTION and ABOMINABLE FALSEHOOD,’ and said he had ‘FLAGRANTLY LIBELLED TRUTH.’ These handbills were printed by Robert Peck of the Hull Packet – who, like many newspaper printers, was a vendor of patent remedies and was firmly on Butler’s side.

I don’t know whether Clayton’s grief and campaigning activities led him to neglect his business or whether he was already in financial trouble, but he was declared bankrupt about a month after his son’s death. Although the newspapers hadn’t reported the poisoning, they were quick to advertise the sale of all the Claytons’ property. In a particular act of despicableness, Robert Peck allegedly turned up at the sale and boasted to Mrs Clayton that her husband would not get away with the libel.

Clayton wanted to take the precaution of getting a written copy of the coroner’s verdict, but when he went to pick it up, he discovered that the coroner ‘had not time’ to do it. The Deputy Town Clerk was equally unhelpful, but it turned out that Butler was all talk and never went ahead with the prosecution.

By 1805 Clayton must have managed to get back in business as a printer, because he published An Essay on Quackery, and the dreadful consequences arising from taking advertised medicines; with remarks on their Fatal Effects, with an account of a recent death occasioned by a Quack medicine. The author is anonymous and is usually assumed to be Thomas Clayton himself, but I believe it to be his brother, M. J. Clayton. The 140-page essay appears cobbled together, is understandably emotional, and it reproduces lots of excerpts from other writers, but it also offers a measured, sensible list of recommendations for stamping out quackery by replacing the government’s quack-related income with duties on other activities.

This government revenue was substantial and goes a long way towards explaining why dangerous medicines were allowed to continue. Each bottle or packet had to carry a stamp – some quacks portrayed this as being a mark of official approval but, like most things in life, it was solely a way for the government to get money. I only have figures for 1839, but at that point the government was making approximately £49,300 per year from stamp duty, advertising duty, licences, patents and paper duty (for the wrappers that many remedies were sold in). It’s an awful lot of money, but the price paid by families like the Claytons was much greater.

In a letter to the Medical Observer, the Essay author is exaggeratedly humble about his literary talents, but hints at attempts to suppress the book, and confesses himself chagrined at the lack of interest from the medical faculty. He also says that his own two children narrowly escaped the same fate as little Thomas, and so the Essay‘s chilling curse on Butler clearly comes from the heart:

Dire conscience all thy guilty dreams affright,

With the most solemn horrors of the night.

The screams of infants ever fill thy ears,

And injured heav’n be deaf to all thy prayers.

A salutary tale, beautifully told.

I am always impressed by the amount of background research goes into your articles.

Thank you – that’s very kind of you to say so.

Blog post – The tragic story of Ching’s Worm Lozenges: http://thequackdoctor.com/index.php/the-… #history

RT @quackwriter: Blog post – The tragic story of Ching’s Worm Lozenges: http://thequackdoctor.com/index.php/the-… #history

Interesting, lucid post.

When you get into my favourite period (circa 1908) the numbers break down like this:

IR income from quack medicine stamp duty: £333,141 19s 2d

Number of stamped articles sold: 41,757,575!

Wow, really interesting figures – thanks for adding those.

You’d think with a name like

Worm Lozenges that people wouldn’t have wanted to take them! It would put me off, certainly.

Fascinating stuff – many thanks for a great read, as usual.

You are right – not an “ew!” post but rather an incredibly sad one. I love the small insights into people’s lives even though they are sometimes heartbreakingly tragic.

x

Fantastic research and info, unfortunately he was my great x 4 grandfather, do you have any more info on him?

He died in 1800 and is buried at Bunhill Fields in London, his wife, Rebecca, carried on the business and I think she supposedly “refined” his lozenge, their Daughter, Lucy, married a Stanley Howard who was twice her age and already had six children

(she was coerced by her mother, I have her diaries) he was also a “druggist”

best wishes RW

That’s fascinating – I’d love to hear more about your family history. I don’t have any further info on Ching as I just looked into this one episode, which happened after his death, but if you’d like to keep in touch about him, feel free to email me via the contact page.

Best wishes,

Caroline

Thomas Clayton was my 4 X great grandfather. He had married Lettice Huband in 1793 in Evesham but moved to Hull in 1897. Thomas Huband Clayton was their second child, born in 1801 and died in 1804. They had 10 children eventually.

He was declared bankrupt in 1804 but was able to continue trading after he had paid off his debts. He moved to Maidenhead in Berkshire where he continued trading as a bookseller & printer. He was declared bankrupt again in 1812 but again paid off his debts. For a short period he lived in Queen Square, Westminster which was noted for its booksellers. He then moved to Reading where another son, then grandson, carried on the business. Thomas senior died in March 1833 at Reading shortly after his wife Lettice had died in January 1832. They are both buried in St Mary’s Church, Reading.

I’m interested to hear your theory that you think that the treatise was written by a brother. Do you have any evidence for this?

Hi Ray,

Thank you for your comment – I’m very interested to hear of the Claytons’ later life. The evidence for the brother comes from a letter to The Medical Observer, vol. I no IV, Jan 1808. The writer, M J Clayton, claims authorship of the Essay on Quackery and refers to other poisonings occurring ‘Near the time my brother’s child was poisoned at Hull…’ suggesting that M J Clayton was a sibling of Thomas senior. The editors refer to him as ‘Mr M J Clayton’, indicating that he was male – while this could just be an assumption on their part, there is also reference to his own children, suggesting, given the context of the time, that he is married. If M J Clayton were in fact a sister rather than a brother, she would most likely be writing in her married name.

Best wishes

Caroline