‘Tears and prayers are of no use,’ warned the eyecatching pictorial advertisement in the Penny Illustrated Paper. It was perhaps the most truthful statement Arthur Lewis Pointing, proprietor of the anti-drunkenness powder, Antidipso, had ever come up with.

‘Tears and prayers are of no use,’ warned the eyecatching pictorial advertisement in the Penny Illustrated Paper. It was perhaps the most truthful statement Arthur Lewis Pointing, proprietor of the anti-drunkenness powder, Antidipso, had ever come up with.

Or rather, that the advertiser of a famous American nostrum had ever come up with, for Pointing had lifted the copy verbatim from advertisements for Dr Haines’s Golden Specific. Pointing had joined the Alaskan Gold Rush after failing to convince Londoners of the value of his ‘Invisible Elevators‘ for increasing their height. His return to Britain in 1899 saw him bereft of gold but in possession of enough brass neck and borrowed advertising copy to make his fortune. A decade later, he was worth almost £40,000 through the sale of a perennially lucrative commodity – false hope.

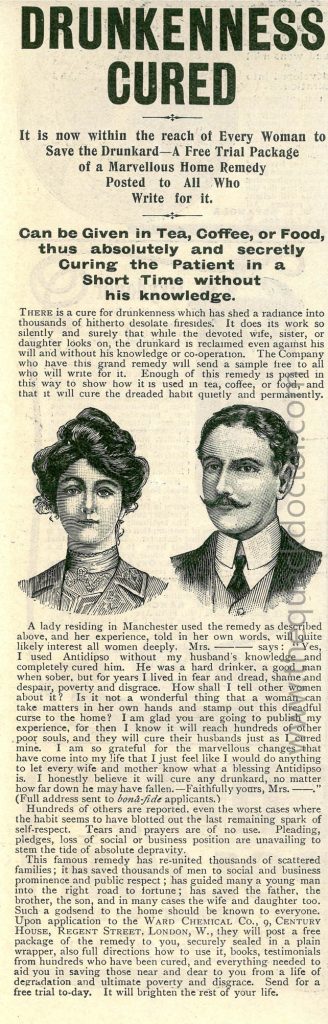

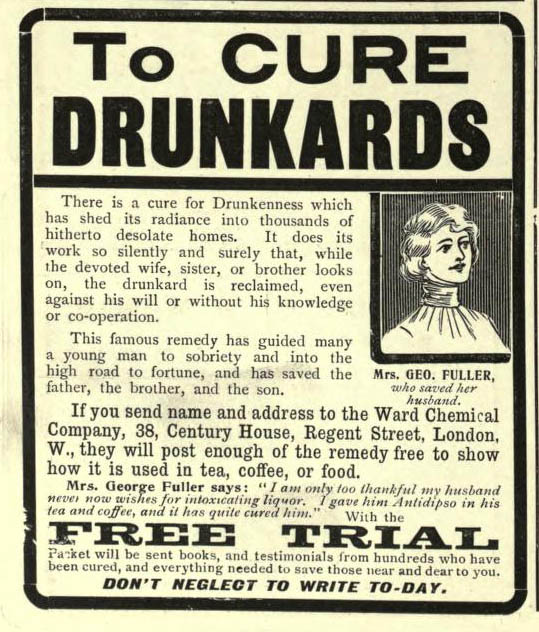

Antidipso claimed to cure the most unregenerate drunkard. Presented as a natural remedy derived from little-known South American herbs, it had ‘shed its radiance into thousands of hitherto desolate homes,’ and ‘guided many a young man to sobriety and into the high road of fortune’.

The number of addicts prepared to send off for a cure was, however, limited, so Antidipso targeted a more receptive market – their loved ones. Enticing enquirers with a booklet called Bright Beams of Hope, Pointing promised that there need be no confrontation, no violence, no broken promises; a powder in the drinker’s coffee would do the job in secret. The unsuspecting patient would be restored to the wholesome embrace of his family and would once again achieve business success and social acceptance. The intended purchaser of Antidipso was not gullible; she was desperate.

And it usually was a ‘she’. Although some of Pointing’s ads acknowledged the possibility of female alcohol addiction, the character of the drinker was almost always presented as male. His saving angel, meanwhile, was his wife. Exhorted to ‘take the matter into her own hands’, the woman with an addict in her life was presented with the prospect of regaining some control over her situation – a situation that it was otherwise difficult to escape. Testimonials told of women who ‘lived in fear and dread, shame and despair, poverty and disgrace,’ using Antidipso to restore the honourable and hard-working men they thought they had married. In luring the addict’s wife with promises of a cure, Antidipso not only propagated false hope but also assigned to women responsibility for male behaviour.

Bright Beams gave a history of Antidipso that shared characteristics with the promotion of other proprietary remedies. Discrediting the medical profession by highlighting its failure to cure addiction, the pamphlet claimed that all the while, ‘an obscure tropical plant was yielding the very remedy that acts as an antidote.’

An analysis in the Lancet showed that the product was 78% milk sugar and 22% potassium bromide, neither of which was particularly herbal nor particularly South American. Although the bromide had the potential to cause nausea, perhaps putting the patient off alcohol, the Lancet concluded that the tiny quantities in the daily dose of Antidipso would not be noticeable.

One packet of Antidipso, retailing at 10s, contained ingredients to the value of about 1½d. The large mark-up, however, was of little concern to the Lancet. Its criticism centred on the heartlessness of a scheme that played on the hopes of vulnerable and desperate people. The sale of an ineffective remedy to those trapped in a difficult situation was a ‘cruel and wicked fraud’ that left an aftertaste more bitter than that of any surreptitiously powder-laced coffee.

To continue with something you mentioned in Great British Railway Journeys, there was a news item today that North Korea claim to have produced hangover-free alcohol…

Sounds legit.