A horrid fate awaited the reader of the Victorian women’s magazine, Myra’s Journal of Dress and Fashion. One day, she would reach the ‘fatal thirty’, a point of life at which ‘the knell of departed youth’ heralded a bleak and wrinkly future.

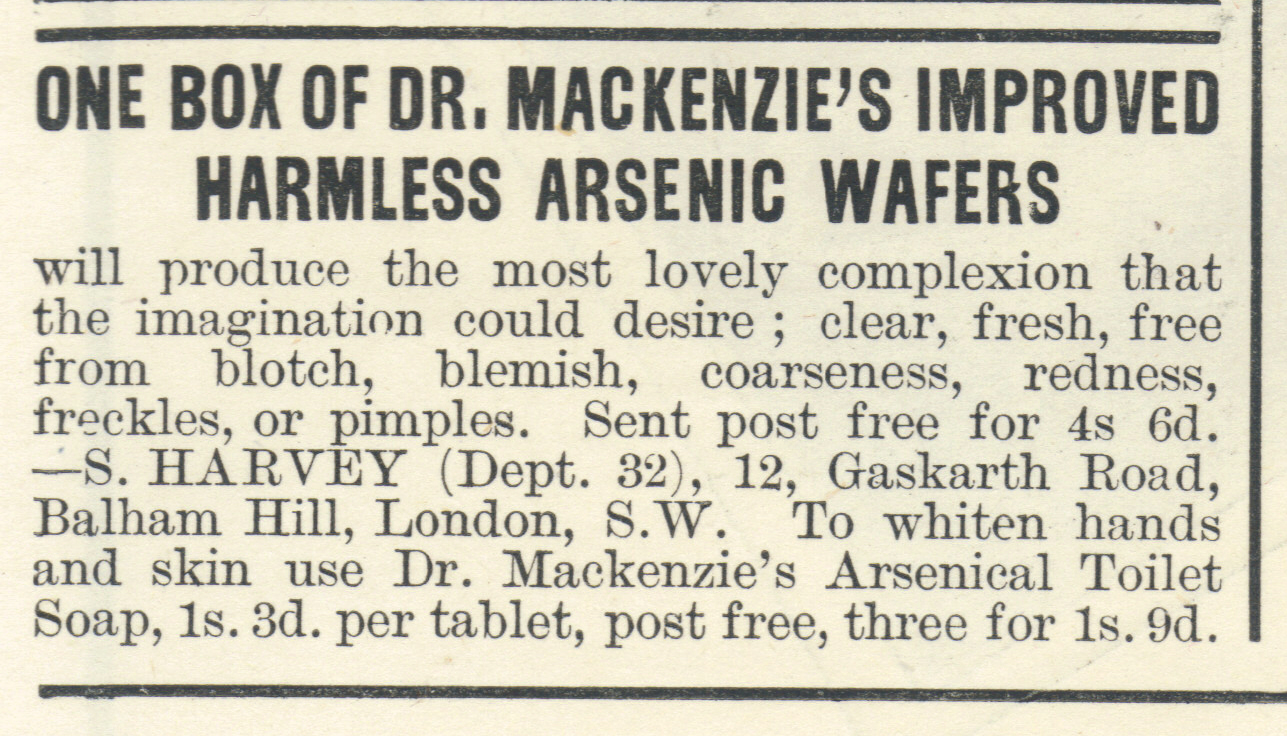

But hope was not lost! One way of avoiding the miseries of aging was to try the Arsenic Complexion Wafers conveniently advertised in the magazine.

Arsenic had enjoyed a long reputation as a creator of translucent beauty and unlined skin. Its use as a cosmetic came under discussion during the sensational murder trials of Madeleine Smith in 1857 and Florence Maybrick in 1889. Both said in their defence that they had purchased arsenic for cosmetic use, Maybrick having soaked fly papers to extract the drug.

The 1890s saw a boom in the advertising of commercial arsenic products specifically marketed for the complexion. Rather than undergo the nuisance and possible incrimination of soaking flypapers, the woman unhappy with her skin could now access a convenient and purportedly safe beauty treatment. And unlike many patent medicine promoters, who concealed the presence of harmful ingredients, these advertisers used the poison as a selling point.

Dr MacKenzie’s Harmless Arsenic Complexion Wafers were launched in the UK in 1893, and they were probably less dangerous than their proprietor – an elusive and rather unsavoury person named Sidney J Hawke. By the time he began selling the pills, Hawke was the wrong side of that fatal thirty but was sufficiently presentable to earn the description ‘a fashionably dressed young man’ during a court appearance in 1892. His trouble with the law, however, was not for selling poison.

Hawke suspected that his wife Catherine, to whom he had been married for only six months, had remained in contact with a former lover, William Dusildorff. She had previously had a baby with Dusildorff and lived ‘under his protection’ until immediately before her marriage, afterwards continuing to correspond with and meet Dusildorff for news of their child. Hawke tried to put a stop to this by sending a menacing postcard to Dusildorff’s business address:

Even your correspondence and telegrams are in safe keeping. At your every meeting you will be followed and watched. You shall bitterly repent it. I am not to be trifled with. It is owing to you and another that I am separated from my wife and my home broken up. The other has paid the penalty, and will show it to his dying day. Your turn is to come in due course. Very well, you shall pay for it.

On this occasion the judge ordered that he enter into his own recognisances of £500 to keep the peace for 12 months. Later that year Mr and Mrs Hawke, plus dog, set sail for the US, returning to London in June 1893.

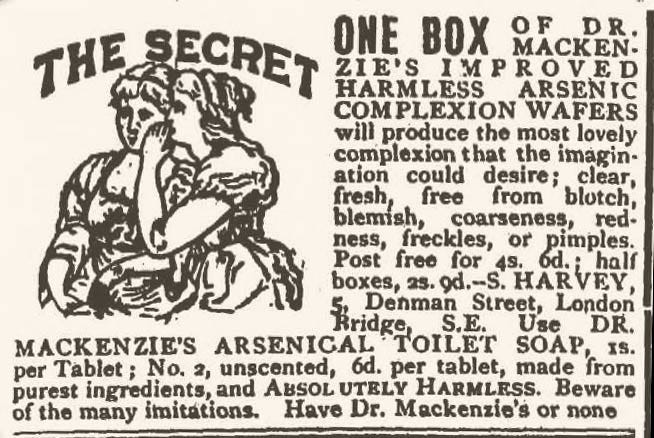

Within a fortnight, advertisements for ‘Dr Campbell’s Harmless Arsenic Complexion Wafers’ appeared in the London papers, promising to ‘produce the most Lovely Complexion that the imagination could desire, no matter what condition it may be in now.’

Within a fortnight, advertisements for ‘Dr Campbell’s Harmless Arsenic Complexion Wafers’ appeared in the London papers, promising to ‘produce the most Lovely Complexion that the imagination could desire, no matter what condition it may be in now.’

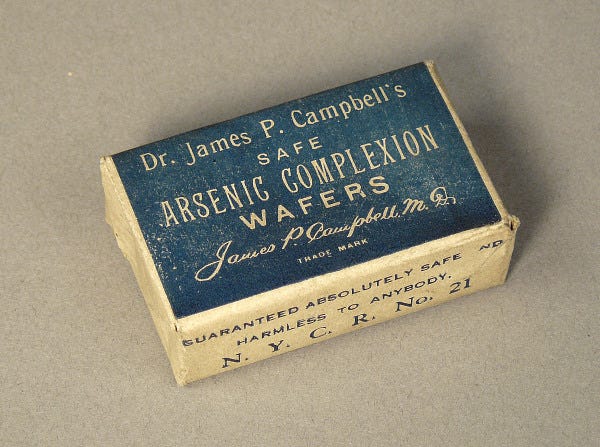

Dr Campbell’s Arsenic wafers – the American brand on which Sidney Hawke based his product. Photo: Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

Dr Campbell’s New York-based brand (which used ‘safe’ rather than ‘harmless’ in its name) had been around since about 1887. Sidney Hawke’s company, S. Harvey, claimed to be the sole UK agent for the Campbell wafers, but it is difficult to ascertain whether this was official or whether Hawke had just decided to rip off Campbell’s adverts. The name soon changed to Dr MacKenzie’s Harmless Arsenic Complexion Wafers, but the advertising details remained the same, from the phrasing of the copy to the picture of a young woman whispering her beauty secret to a friend.

Just as the brand was getting established, Hawke’s presence graced the police courts again after he was violent to Catherine, seizing her by the throat and, when she escaped and ran out of the house, locking her out in the rain until 7 ‘o clock the next morning. Although he denied the attack and claimed Catherine had threatened to shoot him, the magistrate deemed him guilty of assault and fined him £5. Catherine was later granted a divorce after detailing his cruelty and adultery throughout their marriage.

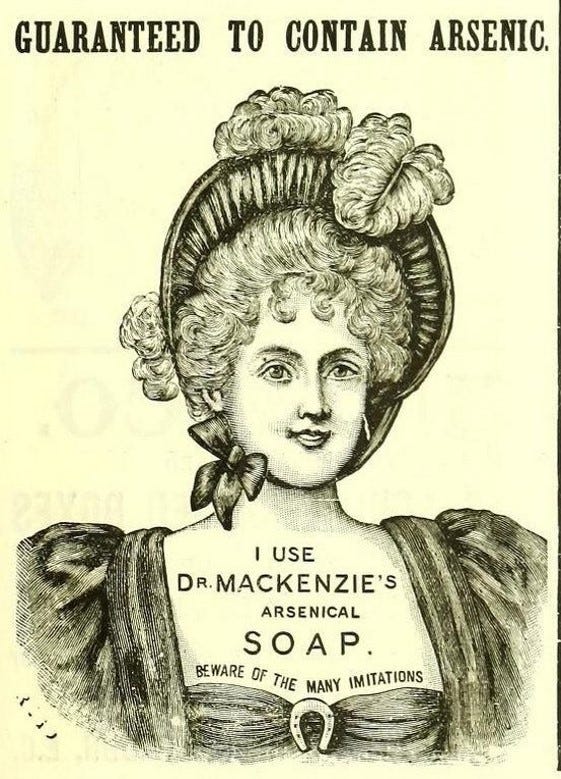

Dr MacKenzie’s Arsenical Toilet Soap appeared in 1895 – a delightfully perfumed, good quality product that proved immediately popular. When shares in S Harvey (Limited) were released for subscription in 1897, the prospectus stated that sales had reached 340,000 pieces a year.

And yet there were no reports of people dropping dead due to using the soap and its many imitators. Could they genuinely be as harmless as the adverts claimed?

During 1896 and 1897, several chemists received court summons under the Sale of Food and Drugs Act for selling arsenic soap, whether they had made it themselves or bought it in good faith from a supplier. And yet, the offence was not that it contained arsenic – it was that it didn’t contain arsenic.

Analysis of samples collected by secret shoppers showed that arsenical soaps contained either negligible quantities of the metal or none whatsoever, and the product could not therefore be considered ‘of the nature, substance, and quality’ demanded by the purchaser. In their defence, the chemists claimed that the soap simply had a fancy name intended to appeal to the increasing interest in arsenic as a beauty aid.

One chemist, Septimus Walgate of Ealing, used one-sixth of a grain (10.8mg) of arsenic per hundredweight of soap. None was discernible in the sample bar, and Walgate’s comment that Sunlight Soap didn’t contain any sunlight either was not enough to get him out of being fined.

In response to these cases, S Harvey Ltd recalled chemists’ stocks of Dr MacKenzie’s soap and replaced them with a new formula, reassuring their retailers that it was now guaranteed to contain arsenic, and indemnifying them against prosecution.

‘Possibly now,’ the Lancet commented unsympathetically, ‘if the soap is used indiscriminately by the public there will be some cases of arsenical poisoning. That, however, is for the public to guard against.’

Sources:

‘The Brewer and the Lady’, The Hull Daily Mail, 20 May 1892.

‘Chats on Hygiene’, Myra’s Journal of Dress and Fashion, 1 March 1895.

‘Arsenical Soap’, The Lancet, vol. 149, 2 Jan 1897.

‘Arsenical Soap Without Arsenic’, The Evening Telegraph (Dundee), 10 May 1897.

‘Cowardly Assault on a Wife’, The Morning Post (London), 7 October 1893.