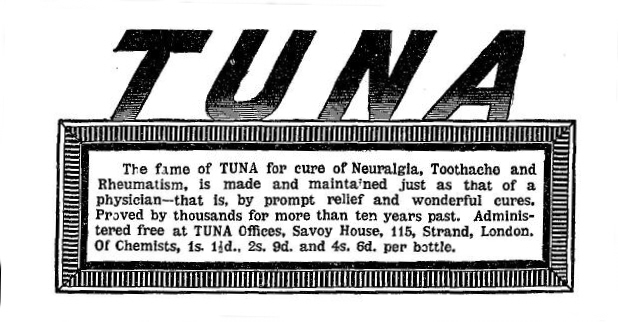

There’s often something a bit fishy about patent remedies, but this one appeared before the advent of canned tuna and, for the average non-sea-going punter, the name did not have the piscatorial associations it has now. A company called Fels and Davis began promoting it in 1879, but by the following year Davis had quietly disappeared from the adverts and the business became Fels and Co.

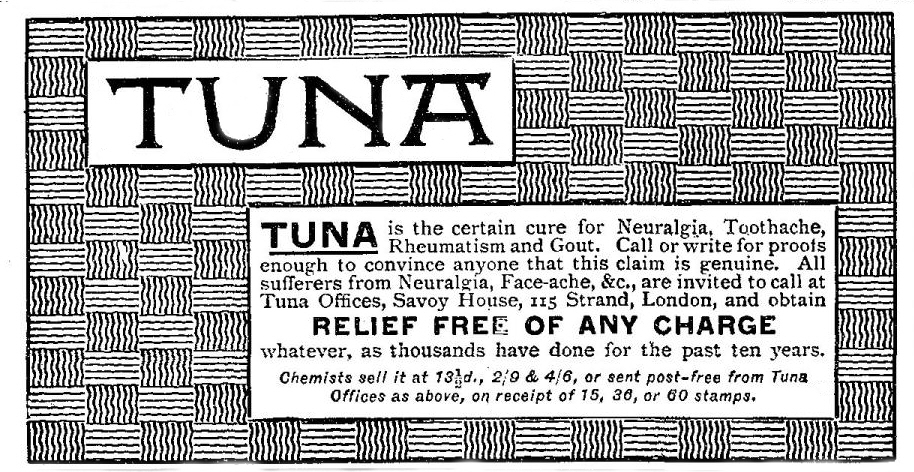

The remedy was promoted as ‘a strictly vegetable compound’, and its trademark suggests that the vegetable in question was a prickly pear species, which produces edible fruit known as tuna. Given that The Strand is not renowned for its supply of cacti, the product wasn’t necessarily made from real tuna fruit, but it’s odd that the advertising doesn’t go all out to create an exotic background story. Instead, the unique selling point was the free dose offered to anyone who called in person at Savoy House.

The experiences of one such caller are set out in a testimonial on an 1879 pamphlet, which is a good example of a proprietor portraying an apparently sceptical customer whose eyes are opened to the wonders of the remedy. The customer, a neuralgia sufferer called J Flynn, starts off thinking of Tuna as ‘only another remedy cracked up by quacks’, and goes to Savoy House purely out of curiosity when he happens to be in the area. After receiving his free dose, he is not convinced, so the Tuna representative gives him another, and still nothing happens. Unable to hang about any longer, J Flynn goes on his way, when the inevitable occurs:

But mark! Before I had gone less than a mile the pain entirely left me, and I have not had the slightest symptoms since, and this was after three weeks’ incessant pain, from which I could barely sleep or eat food.

Flynn goes from writing off Tuna as just another quack potion to viewing it as ‘a godsend to mankind,’ and concludes by thanking Fels and Davis for being ‘extremely kind in curing me and not charging me one halfpenny’. The technique of showing the conversion of sceptic to believer is a common one in patent medicine advertising – here, it’s elegantly combined with a reminder to the reader that there’s absolutely nothing to lose from a visit to Savoy House.